Trying to understand the food-water-energy (FWE) nexus has a lot of us scratching our heads. Trying to get anywhere with it is like unravelling a knotted ball of wool: you can tug at the threads, but they don’t come loosely because it is so intrinsically intertwined. Getting to the bottom of the nexus – if possible! – could be exhausting work. Thankfully for you, we’ve pulled together some of the most succulent facts and figures to set you on the way.

The relevance of the FWE interdependencies really only took off as recently as 2011 when a Nexus Conference took place in Bonn, Germany. It was here that “it was established that failing to recognize the consequences of one sector on another can lead to notable inefficiencies in the entire system”.

What follows are some of the more pressing and relevant snippets about food, water, and energy, which pressures they are facing, how they interlink, and what it all means for the environment.

Food Facts & Figures

Since the mid 1960s, agriculture has increased by 300%. Disproportionately, the land used to produce it has only grown by 12%.

- This overuse of soil leaches to nutrients, reducing the quality, productivity, and local biodiversity.

Food is energy and water hungry!

- The sector’s production and supply chains consume around 30% of the world’s energy, most of which derives from fossil fuels. That’s bad news for the climate.

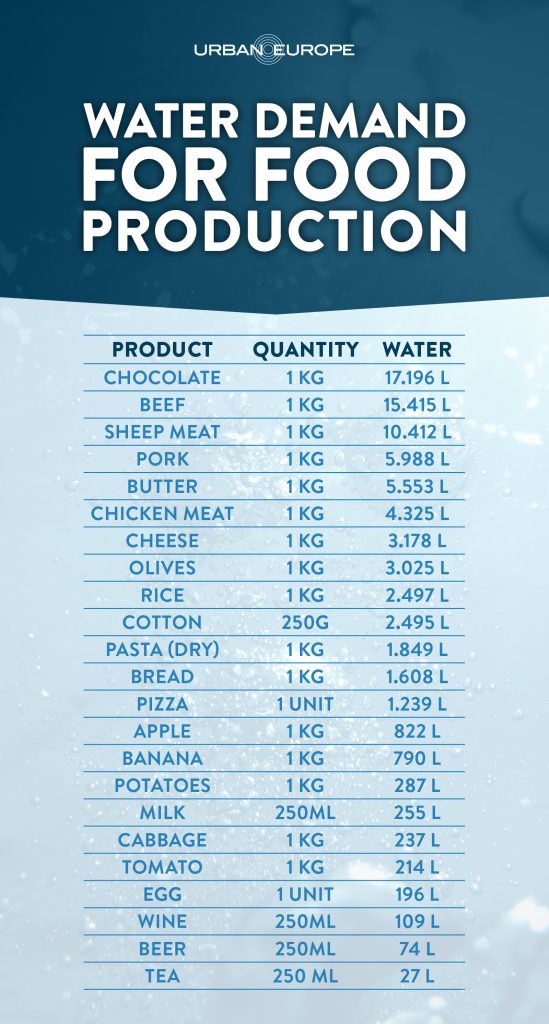

- One kilogram of soya needs 2,000 litres of H2O to grow; the equivalent of wheat requires 900 of the wet stuff. The table below compares demand for water for other common foods:

The water and energy that goes into producing all the food which is wasted in South Africa in a 12-month period could power Johannesburg for 20 years and fill 600,000 Olympic sized swimming pools! Efforts to improve efficiency could see this put to use.

Water Facts & Figures

Water. It’s a basic human right.

Some say it’s sand, while others say concrete: whatever is the second most-consumed resource on the planet, what they do agree on is that water is the first. Scary, then, that access is threatened not just by ever-higher demand, but also climate change.

Globally, only 3% of water available to us is fresh and potable.

- That means 97% of available H2O is saltwater and unusable for drinking, growing crops, and animal rearing.

- 70% of all available freshwater is used for agriculture. Regions vary, but in Sub-Saharan Africa, as much as 80% of water extracted is used in agriculture.

- Of all water we withdraw, 16% is used by municipal services and households, while 12% is expended by industry.

UNESCO predicted in 2018 an annual global water demand increase of 20-30% up to 2050.

- This isn’t all because of food and energy needs. In 2014, the same organisation said a 400% rise in manufacturing by mid-21st-century would accompany a 55% growth in water demand globally.

The nexus presents opportunities for salvaging stretched resources.

- Aquaponics breeds fish as food in cities. The waste they produce is used as fertiliser for vegetables. The plants purify the water, reducing how much is required for the fish.

- This has the potential to produce many tens of kilotonnes of tomato, lettuce, and freshwater fish products. In cities like Berlin, with a population of more than 3 million, this can “save about 2.0 billion cubic metres of water” per year.

Energy Facts & Figures

Electricity is still short in supply in many developing nations, primarily across Africa and Asia. Blackouts are not unusual.

- These areas will face the fastest increase in populations in forthcoming years, disproportionately affecting already limited supply.

Power generation requires some kind of fuel: 90% of the time this is water-intensive.

Many countries use freshwater for cooling power plants:

- In Europe, 43% of freshwater is used for these purposes.

- This rises to almost 50% in the USA.

- In China, it’s only as much as 10% of the national water demand.

More efficient power plants requiring advanced cooling systems may drive up the volume of water withdrawal by 20% by 2035, as their consumption rises by 85%.

The State of Things to Come

In 2021, 55% of all humans lived in urbanised areas, packed into just 2% of all dry land.

- This extreme density concentrates higher consumption rates in localised areas, meaning “urban areas are the main consumers of resources”.

- The nexus is not a closed system. Meeting this demand requires supply chains stretching outside the city limits.

From 2020 to 2050, the projected number of people living in cities will double. According to the UN, that will mean two-thirds of a global population of 9 billion with reside in urban centres.

As populations continue to increase, so does pressure on finite supplies of food, water, and energy. Developing nations will be some of the worst affected. In Africa, for example:

- The population will hit 2 billion by 2030.

- Compared to 2019, this increases water consumption by 283% (or a 30% rise for drinking water alone compared to 2012)

- In the same period, demand for energy will rise by 70%.

- Pressure on food will rise 60%.

Social Issues

Inequality blights access to food. A 2021 report from the United Nations calculates that “3 billion people cannot afford a healthy diet”.

- A shock to supply lines and incomes – such as a natural disaster – could see that figure sore by a further billion.

- Food security created by a more stringent nexus policy could buffer this impact.

According to the United Nations, water scarcity will affect 1.8 billion people in 2025. At current rates, by 2050, that will rise to 5 billion.

The World Wildlife Fund writes: “It is predicted that by 2025, most countries of Africa and West Asia will face severe water scarcity due to increasing population and demands on water.”

- Several countries across the Middle East, North Africa & South Asia are already experiencing “extremely high levels of water stress”.

Environmental Matters

We’re talking about three resources, so it stands to reason their combined carbon footprint is considerable. The combined access, extraction, and consumption of food, water, and energy rack up 70% of CO2 emissions.

It’s important we review our relationship with the nexus. Climate change poses many challenges. Changes to hydrological cycles will cause more floods and droughts, making “it more difficult in the developing world to grow crops, raise animals and catch fish”. That makes it a pressing social – even humanitarian – issue.

A healthy, integrated FWE nexus can help us hit climate goals.

- Sound resource management can “increase the efficiency of natural resource use” as well as “reduce CO2 emissions and waste generation”.

Note: This article is commissioned by and produced in collaboration with JPI Urban Europe, a European research and innovation hub founded in 2010. JPI Urban Europe funds projects which address the global urban challenges of today. To make the food-water-energy nexus (FWE nexus) more tangible and the results of successful, funded projects in this context accessible to a wider audience, JPI Urban Europe collaborates with CityChangers.org. Details about JPI Urban Europe can be found on the respective websites linked throughout the article, which was originally published here.