Spend less and save the environment: these are the benefits of repairing durable household electrical appliances over buying cheap replacements every few years. The fact we even can give products a second lease of life is largely down to Right to Repair hero, Sepp Eisenriegler. He tells us what’s wrong with warranties, why manufacturers are changing business models, and how Austria serves as an example of commitment to repairs at local and state levels.

According to UN Environment’s Global Resources Outlook, “90 per cent of biodiversity loss and water stress are caused by resource extraction and processing”. This emits about 50% of all global greenhouse gas emissions even before anything is done with the materials.

Energy use in production accounts for more than 24% of GHGs[1], hinting at the destructive force of the manufacturing sector. Drill this down to household appliances such as washing machines, and Sepp Eisenriegler understands that “53% of the overall environmental impact is caused by production and distribution”. And when items no longer function, we need replacements. It starts all over again.

There are alternatives that bypass this linear ‘take-make-dispose’ process, while assuring the quality of products we’re accustomed to and serving a healthy economy.

The circularity model is one of ‘take-make-use-reuse’. It’s common to think of this in terms of material recovery – recycling components of a defunct product to create a new one – but is there more to it?

The Promise of Repairs

Repairing goods extends their lifespan, easing demand for new products and therefore reducing production-based emissions.

“Repair is the King’s discipline of a circular economy.”

Better still, says Sepp, would be to make them to last longer in the first place.

These changes are systemic, dealing with the problems inherent in linear production: appliances are made to break and not allow repairs.

Planned Obsolescence

In a saturated market – where almost every home has white goods like a fridge and washing machine – appliances are created badly and with an inbuilt expiration date.

Planned obsolescence often occurs, Sepp maintains, shortly after the warranty expires so that consumers must buy new ones. For small appliances like a toaster, this is as little as two years.

“The reason for behaving in this idiotic way is an obsolete economic system, which is based on growth.”

Plus, they’re constructed in a way that repair is almost impossible. Have you ever tried replacing the battery in an electric toothbrush, for example, or fixing your smartphone screen? Until recently, it couldn’t be done. Sepp has helped change that.

Circularity Standards and Regulation

Sepp leveraged his membership of European standardisation organisations such as CEN and CENELEC and ETSI to push for circular practices across the EU. The basis of this was the more stringent regulations of Austria’s national standard for electrical goods, ONR 192102:2014.

The resulting EN4555X series of EU regulations set out industry standards for the durability, reparability, reuse, and upgrade of products, while Sepp’s input to the PROMPT (PRemature Obsolescence Multi-Stakeholder Product Testing) programme explores ways to force an end to planned obsolescence.

He has gained some ground: the Ecodesign directive dictates that producers of electrical goods “have to provide consumers and independent repair shops with spare parts for 10 years”.

It makes a considerable difference. Sepp refers to the European Environmental Bureau’s 2019 Coolproducts Don’t Cost the Earth report, which found that “[e]xtending the lifetime of all washing machines, notebooks, vacuum cleaners and smartphones in the EU by just one year” could save the equivalent emissions of more than 2 million cars by 2030.

Changing buying habits allows consumers to passively and positively change their impact on the environment.

Repair Bonus

Taxes levied on repair services, Sepp explains, are high in Austria. He would like to see them redirected to the point of resource extraction to deter unstainable industrial activities.

For now, simply making repairs possible wouldn’t go far enough. Knowhow and incentives are required to ensure consumers make use of these possibilities.

Sepp leads by example. Based on the blueprint of his Repairnetwork Vienna, he helped to create Graz Repariert, a network of repair services in Austria’s second largest city to make repairs easily accessible.

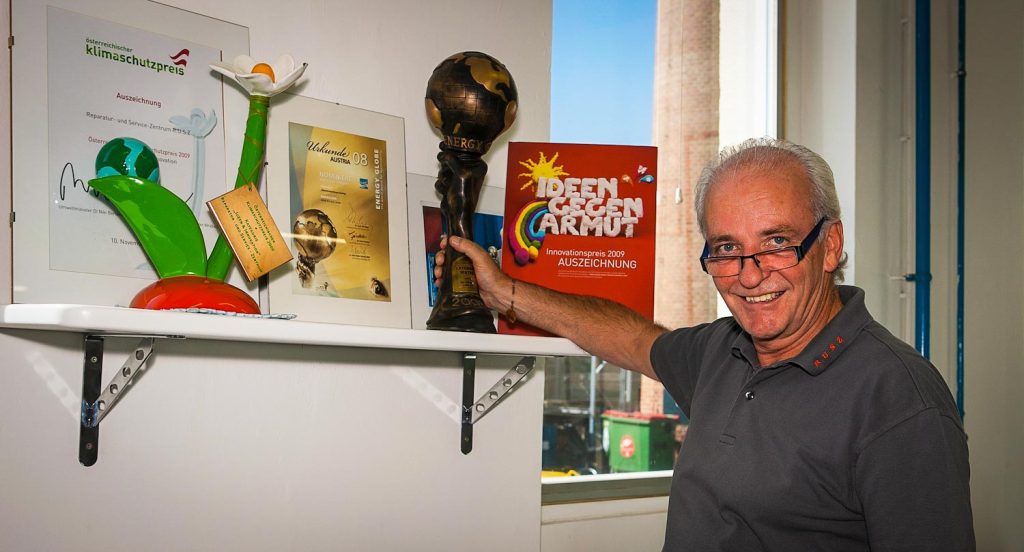

Around the turn of the century, he founded and still runs the Reparatur- und Service-Zentrum R.U.S.Z. (Repair and Service Centre) in Vienna. It began as a work integration social enterprise, giving defunct electrical appliances a new lease of life by offering professional repairs at affordable prices.

It privatised a decade later and struggled to stay afloat with its relatively cheap rates until Vienna introduced the Reparaturbonus, boosting interest in repairs. The scheme rolled out Austria-wide in April 2022.

Under the scheme, customers pay half, and the workshop claims the rest (capped at 200 Euros) directly from the government initiative. That’s essentially a half-price repair up to the value of 400 Euros for electrical and electronic devices.

It’s so successful, the centre has a three-week backlog and repairs around 12,000 items annually.

Giving Appliances a Second Life

The Repair Centre offers a range of services besides straight fixes, which maximise the scope of product reuse and longevity:

- Washing machine rental, charged on a per-use basis.

- Spare parts store for DIY repairs.

- A Repair Café where, pre-COVID-19 pandemic, people were guided to fix their own items: 85% of those brought in were reparable.

- Sale of refurbished ‘Second Life’ appliances.

“We get about 1,400 washing machines a year donated by Viennese households, and 30% of them we can prepare for their next life cycle,” Sepp explains. ‘End of life’ products – those that are beyond reuse – are cannibalised for spare parts.

Urban mining “is the last resort to me”, Sepp says of material recycling. “It is not bad, but it’s the worst of the good things you can do.” It does at least cut down on waste going to landfill.

Longevity and Limits

Repairing saves on CO2 output, but also avoids buying cheap replacements; these are a false economy.

Sepp has observed that each 100 Euros spent on poor-quality appliances costing below €550 correlates with how many years it will work: “A €300 washing machine is built to last three years”, he informs us.

Renowned brand names that cost more upfront need to be replaced less frequently: a 900 appliance, Sepp explains, could last 20 years or more and still be repaired. Consumers choosing a 300 Euro alternative would need six replacements in that time.

This rings potential alarm bells in terms of equality. Low-income households pay more than double in the long term. They’re penalised for their poverty.

However, the Repair Centre offers second-hand machines from brands such as Miele, Bosch, Siemens, and (Austrian brand) Eudora at “the price of a throwaway washing machine”, making it affordable and attractive.

Their work even carries a year-long guarantee, galvanising trust that, our CityChanger adds, is being eroded for many manufacturers by planned obsolescence.

And as your friendly neighbourhood repair shop, Sepp’s team are flexible with the warranty: “If anyone has a problem one year and a day after they have bought a Second Life product at our place, we will never tell them it’s too late.”

Industry Responses

One might expect friction from manufacturers who view repairs and resales as undermining their consumer base. Sepp admits that he overestimated the level of resistance.

In meetings with industry representatives, he realised that manufacturers accepted their responsibility towards circular economy practices. The disconnect was instead in thinking “they could produce as they used to, and that they had to improve recycling”.

He worked with a wide range of stakeholders, from industry lobbyists and the European Commission to NGOs and member states ministries to change this misconception and influence better processes.

“We start with product design. We have to design technical products which last. We have to design them so that they can easily be repaired.”

Changing Business Models for a Strong Economy

Bosch Siemens Hausgeräte is one company that adapted their business model accordingly. Like the Repair Centre, they too now rent out appliances to end users.

It’s in their interest to keep products running for as long as possible, so BSH constructs robust machines that are easier to repair and employ skilled technicians to maintain them.

Getting the right personnel isn’t easy. The Repair Centre would like to have more franchising partners, “but they could not find repair technicians” who would make this viable.

To plug a gap, Sepp started an initiative to train qualified repair technicians within half a year. It “was simply too short” to learn what they needed.

He’s now in talks with Austrian labour market services to extend the programme with regional government funding.

A generation raised on green messaging have different priorities to those who came before, so there are indications that young people will take up opportunities to train as future repair service professionals. In Austria from 2023, mechatronics apprentices will have chance to train as repair technicians after completing their basic education.

Going Circular – Your Easy Guide

Gone are the days when the newest, most expensive branded goods held the most social sway:

“I’m confronted with more and more young people who regard having things repaired and buying Second Life products as a status symbol. This is what I realise they prefer nowadays, and that’s great.”

But we can all be part of the transformation, Sepp points out. And it’s as easy as choosing what we buy – or choosing not to.

The circularity expert reiterates the easy action that consumers can take:

“Make use of your products as long as possible. Don’t change them too quickly. Don’t replace them after their first failure but have them repaired.”

He also advocates for discriminative purchasing, to be critical with what we buy – do we really need this new-fangled gadget? Should we really opt for the cheapest choice?

Quoting Niko Paech, who plays with a Beatles song title, Sepp summarises that cutting our individual CO2 footprint is “very easy for everyone to understand: ‘All you need is less.’ Then you make a contribution to our climate change. Everyone can do that.”

[1] Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser and Pablo Rosado (2020) – “CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-other-greenhouse-gas-emissions’ [Online Resource]