Public participation matters. It brings democracy and diverse perspectives to city design. But it can be difficult to get right. Smart technology hands us new opportunities for engagement. Today we learn about one of the pioneering tools in this field – Maptionnaire – and get pointers from the experts in increasing your reach in consultations.

How do we build a city that people want to live in? The short answer: by asking them what they want.

These days, an urban planner worth their salt consults with the communities they serve and delivers on the feedback. Naturally, the more participants, the truer the representation. That’s why decision-makers need to attract a broad demographic and numerous responses from the neighbourhoods they are active in.

One way of doing that is employing tools suited to the task.

Put It on the Map

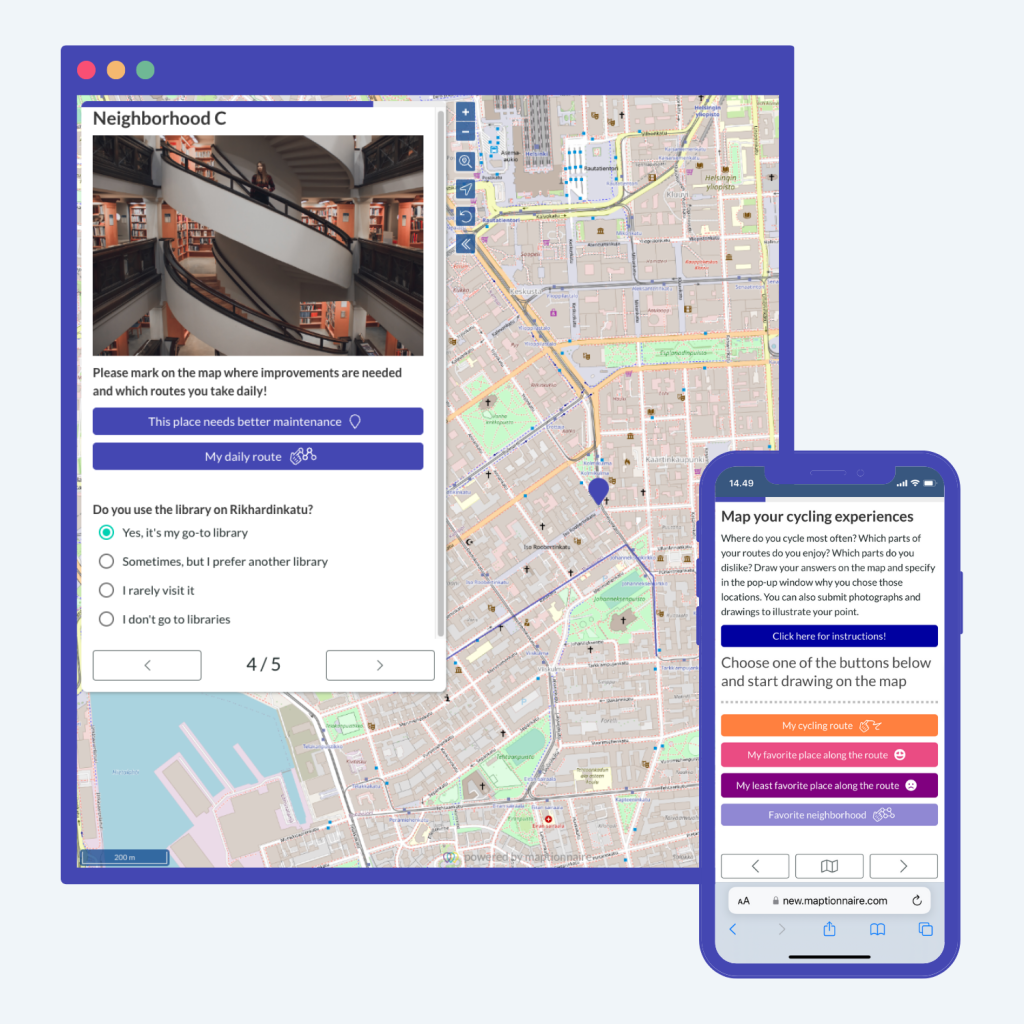

Enter Maptionnaire, an aptly named citizen engagement platform with online spatial surveys at its core. It provides a visual representation of an urban space in map form, on which planners can directly pose pertinent questions.

End users get to see the challenges and/or proposals presented in a geographical context, enhancing their comprehension and ability to formulate informed answers.

Spatial questions – for example, “Where is your favourite green space?” and “Where should there be more street lighting?” – can be answered with a simple click.

It can also be used to gather qualitative responses: open text fields invite comments on an area, feature, or planning proposal in the city.

Maptionnaire collates quantitative and qualitative GIS (geographic information system) data, which can then be easily analysed and compared, removing ambiguity and the need for interpretation.

The software was developed by the founders of Mapita, Maarit Kahila and Anna Broberg – CEO and COO respectively.

They knew that they didn’t need to reinvent the wheel. The “online consultation sphere” partially replicates methods used in traditional townhall meetings, Anna tells us, such as “discussion boards, vision surveys, and voting”. By throwing geospatial data into the mix, Maptionnaire enhances this traditional consultation toolkit with “robust spatial functionalities”. Pretty neat!

Going digital does have other advantages too. Being online, more people can access a citizen engagement survey, and timing is flexible. That matters; genuine representation is a matter of equity.

Why Diverse Participation Matters

In public meetings, we always hear from the same loud voices.

Maybe surprisingly, we don’t want to drown them out, but we do want everyone to be heard equally.

It will never be perfect, our CityChangers point out. Some people just don’t cash in their democratic rights. It’s the same in elections.

We can, however, improve access for those who welcome it, as Maptionnaire has proved.

This was demonstrated in a land management project in Peja, Kosovo. Surprisingly, it wasn’t tech-savvy young men who engaged with the digital tool the most, but middle-aged women – a demographic, Maarit confirms, that isn’t typically engaged with urban planning processes.

“Within just ten days of launching the Maptionnaire survey,” their website claims, “the municipality had received 1,663 responses” – more than double the attendance of the public meetings. It attracted a 45% female response rate compared to the rate of female submissions in-person of just 5%.

That’s a triumph! But that brings us to our next question: is an increase in participation ever a bad thing?

Participation – A Planner’s Conundrum

The year 2000 ushered in a new stumbling block for Finland’s urbanists: the requirement for urban planners to always seek consultation.

Maarit explains how they would go about it backwards: draw up a proposal, and then hope to get the official document passed at a public hearing.

Suddenly, the people had more influence.

If they objected to an idea, “this prolonged the processes a lot,” Maarit continues. Appeals taken to court often ended with the plans being quashed altogether.

The result? Underutilised land, resulting in missed revenue and lost opportunities for housing and new businesses, Anna adds.

Transparent community engagement at an early stage is proven to help avoid such disappointment. This explains why Maptionnaire has been involved in more than 14,000 projects since the company formed in 2011.

The People’s Perspective

Our CityChangers admit, though, that this is a top-down process. It has to be. The municipality is uniquely positioned to reach the spectrum of a city’s stakeholders and hold the power – and budget – to turn findings into street-level change.

To level the field slightly, some cities hand some of that power back to the citizens.

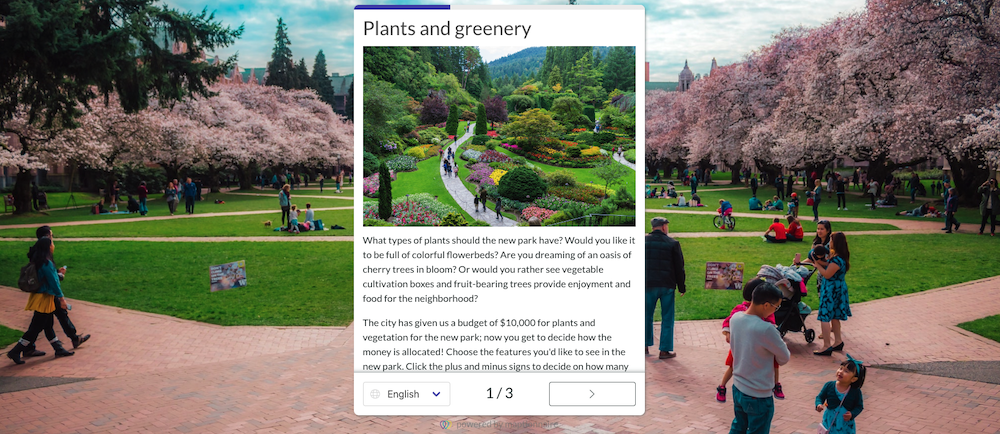

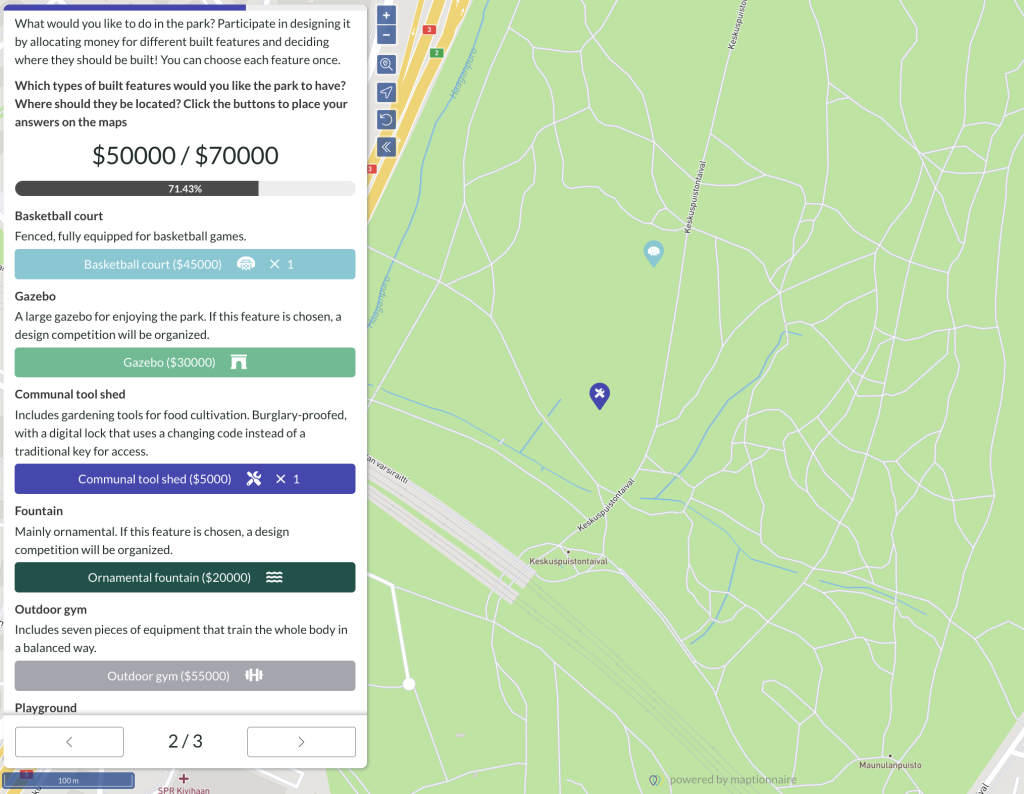

Participatory budgeting allows citizens to make firm and transparent decisions on spending, and Maptionnaire facilitates this complex process with a special module. But the platform also offers a low-threshold alternative for budget prioritisation called geobudgeting: the survey presents options for where and on what the money can be used for.

.

Even so, one of the greatest barriers to participation is citizens’ own mindsets.

A few days before our interview, Maarit was asked by a workshop attendee whether planning shouldn’t be left to the professionals – those who really “understand” what a city needs.

Despite missing the point somewhat – city design should reflect the needs of the people, not the other way around – it’s a fair question.

Democratising city planning raises an interesting philosophical debate. Just because the majority wants or expects something, does that make it the right choice?

If 85% of people responding to a mobility survey turn out to be drivers calling for traffic relief, could we justify building more roads?

What if those responses only represent, say, 30% of citizens? Are planners duty-bound to make good on promises to follow through? If they’re ignored, what detrimental impact will that have on future engagement activities?

Maarit has reflected on these themes on Mapita’s blog. She believes that tech is an effective way to include diverse voices over time, not as a one-off. Neither a single survey nor a single tool is enough.

Diversity Data Collection

It’s important to allow people to engage in different ways.

“We should not think of these types of tools as the only tools. There always has to be different kinds of channels,” Maarit explains.

Some people still feel more comfortable in a face-to-face setting. “That should be possible as well.”

So, public meetings are still on the table.

This was demonstrated recently in an old military barrack ground in the Pihlajaniemi area of Turku, Finland, which has now been redeveloped as a residential area. This small municipality’s survey pulled in hundreds of responses, but only two in a public meeting of 60 were among those ranks.

The two formats appeal to different audiences. Each complements the other. Progress doesn’t mean disposing of what we got right in the past.

Don’t Wait for People to Act

Digital tools work extremely well. However, Anna suggests that planners should not just post a link online, sit back, and wait for the responses to flood in. Social media marketing appeals most to younger age groups. It’s not enough.

You need to be very tactical and recruit local residents from the groups that you’re trying to reach.

Anna Broberg

Ambassadors, community leaders, and citizen groups can be effective allies in promoting your survey.

Take Helsinki, for example: during their master planning project, the city integrated a survey into their popular blog.

And Tallinn, in Estonia, who ran a public art survey in three languages to capture the opinions of the local communities and – unusually in city planning – international visitors. In another development project in Tallinn, QR codes, hyperlinking to the survey, were made available around the city to spark curiosity and spontaneous engagement.

If there’s a chance, Anna advises, meeting people to walk them through the survey (“assisted answering”) extends reach even further.

One Last Hurdle…

For all Maptionnaire has taught us about effective surveying, our CityChangers see one area that still needs a lot of improvement: we’re asking really bad questions!

The questions we pose need to be relevant, easy to understand, and result in answers that fill in gaps in our knowledge – not replicate what we already know.

You only get data as good as your questions, Anna stipulates. “The content has to be very focused and precise.”

What’s the secret? Try to be concise, Anna adds. Don’t ask pages and pages of questions “but really think about what is relevant in this situation right now and then do that well”.

Use easy, friendly language. And remember: you’re asking people to invest their time, and they have limits. Sometimes less is more.

Give It a Go!

Like the sound of spatial surveys and want to try it out for yourself? Play around on Maptionnaire’s fun engagement demos here.