With water flowing in from beyond the city boundaries, how can we realistically keep it in check? The International Water Association’s 17 principles for water-wise cities may hold the answer. In this article, we take you through the basics of urban water resilience and management. It’s an ideal starting point for any wannabe water-sensitive city.

We live in a world where only 2.5% of water is fresh enough for use. Agriculture stands as the biggest consumer, followed by industry. People and services are allocated the least.

We also face a triple threat: demand for water grows as populations boom; climate change has made weather systems erratic; and urban sprawl will continue to make building-in fair and effective water management trickier.

Meeting the future needs of our cities and inhabitants requires change today. But the solutions we put in place must be flexible enough to adapt to changing and unpredictable demands. This is what a water-sensitive city looks like.

A Water-Wise Starting Point

It’s worth noting that the two terms ‘water-sensitive’ and ‘water-wise’ are used interchangeably: there’s no agreed definition separating the two. The International Water Association (IWA), however, uses the latter in their 17 Principles for Water-Wise Cities.

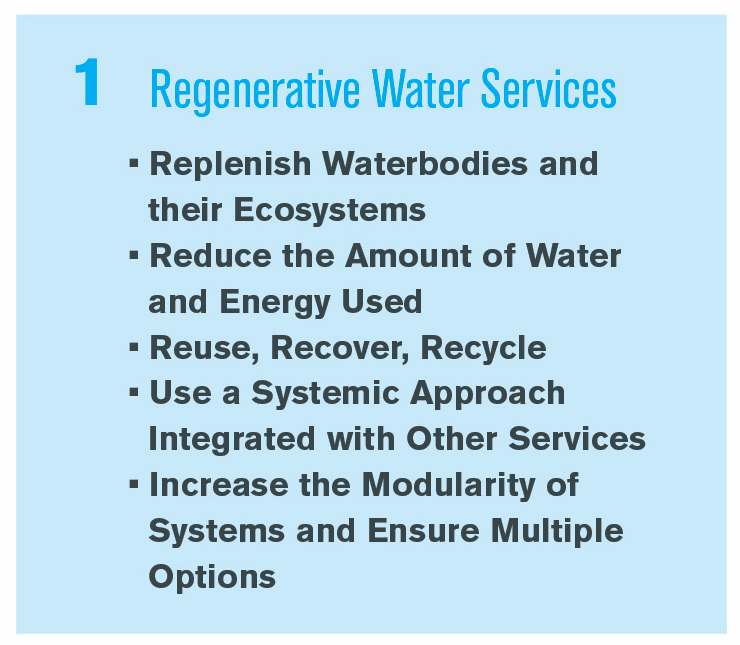

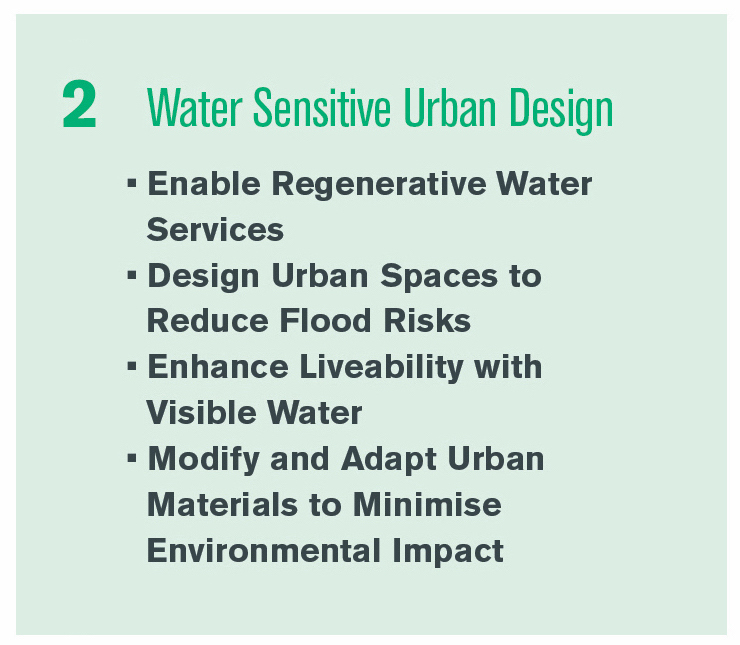

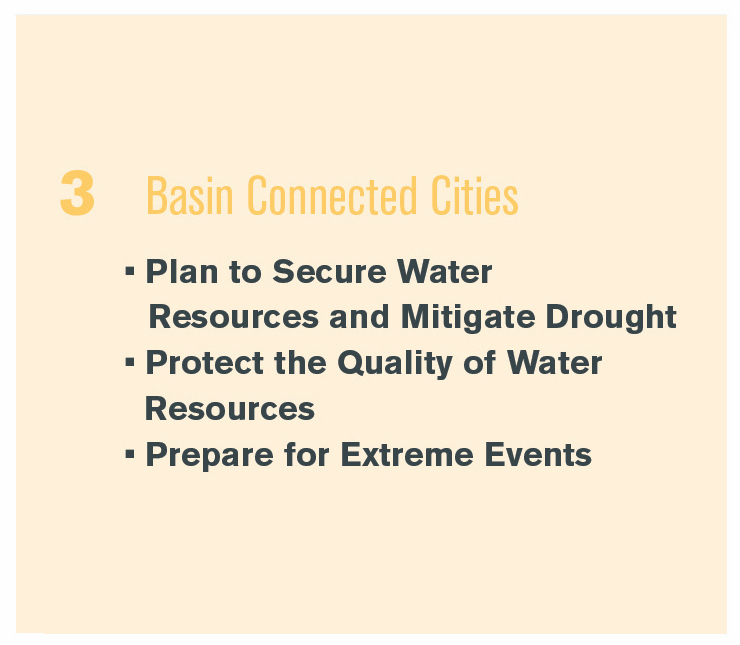

At their very core, these are a set of actions that assist leaders in defining the water-centric needs of their city and outline what a hearty response calls for:

.

What’s neat is that these can be used as a starting point by any city, regardless of how wet or dry it is, the level of pollution it experiences, what infrastructure is in place, or how (un)successful the local systems are at coping with the demands on or caused by water.

Notice the principles are segregated into four categories. That’s because the actions apply to specific scales. The first three are geographical:

- Local scale: localised structures, such as water pipes and sanitation services, that can withstand and mitigate shocks caused by population and climate change.

- City scale: the physical urban space itself, built in a way that is water sensitive. Basically, this covers city-wide infrastructure and how systems interact.

- Basin scale: this looks at how the geographies of the natural world and cities interact, preferably harmoniously: water flows from and back out to rivers, coasts, storm- and meltwater, reservoirs, etc.

How to Implement the Principles

Think of each scale as a concentric ring.

Cities should look at them in turn – starting at the centre (the local scale) – and use the principles to establish their water-sensitive status.

Eliminate the unnecessary actions – those that do not apply to your city or which have already been met.

Of those that remain, choose an action and set it in motion. When complete, move on to the next. You don’t have to approach them all at once. It’s better to do one well than fail at them all.

If a full set of actions within a scale have been achieved, congratulations! Move up a step.

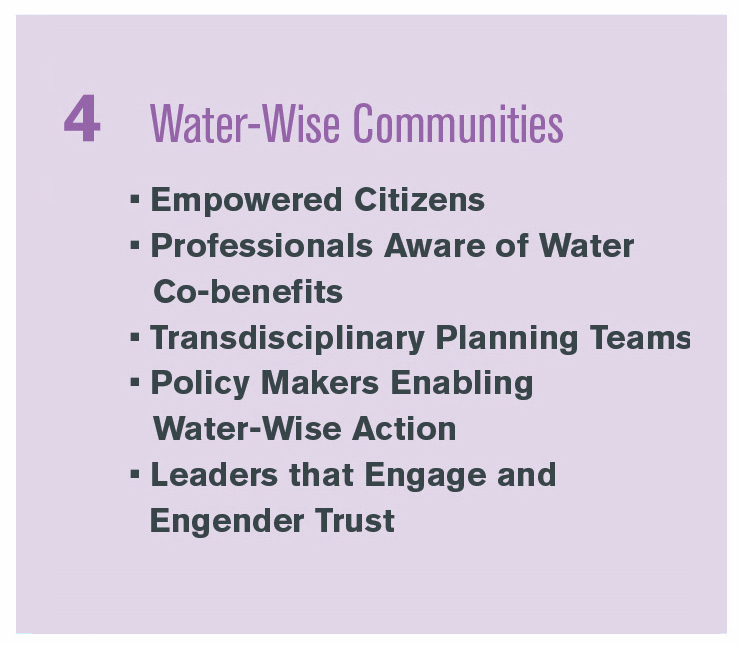

Water-Wise Communities

The final series of principles is a little different. Water-Wise Communities adds a social context and should accompany the actions of every scale to reinforce resilience.

Daniela Bemfica, IWA’s Strategic Programmes & Engagement Director, explains that these five principles should be considered alongside the actions of the other three scales, not independently.

Water-Wise Communities focuses on how citizens, water professionals (e.g. engineers), policymakers, and politicians should have a chance to participate in the decisions affecting their city. They should be encouraged and enabled to share their water-wisdom, based on lived and expert experiences.

“If you don’t at least consider the fourth one, you tend to fail,” she explains.

This ‘failure in the fourth’ is an experience Daniela encountered first-hand, in her former urban water manager position in Brazil. She openly recognises that she and her colleagues in the city didn’t empower citizens at that time. “We just informed them, and we thought that we were doing great.”

It was certainly an improvement. No one had informed the people before. But it was only the start. “We didn’t really manage to get them as advocates for us, as allies.”

We didn’t realise that we need to get people on our side. If I had known those circles, it would have helped us to realise that. Maybe it would have made a difference.

Building Blocks

Look back at the image above and you’ll notice five icons representing one final layer of guidance: the building blocks of water-sensitive cities.

These are good practices that, if implemented well, empower stakeholders to recognise and contribute to water-sensitive cities.

For an in-depth look at what each involves, read the original principles document. But to give you a basic understanding, here’s our summary:

A Shared Vision

Create a mutual end goal for everyone to work towards. Ensure political commitment outlasts election cycles. Push for new policies and strategies at multiple scales that benefit the entire city ecosystem to extinguish silo thinking and bring together multiple disciplines to work on a collective objective.

Governance

Leaders must take the initiative and lead on the shared agenda. With their overview of the city and links to all people and professionals within their jurisdiction, municipalities can provide a framework for integrated solutions and multi-stakeholder collaboration. This needs to be implemented in services at each scale, from buildings (the first scale) to basins (the third).

Knowledge & Capacities

Technological and social challenges can be tackled with education and knowledge-sharing. Improve the capacity of citizens and professionals to contribute to resilience and resource management with upskilling programmes. Bolster enthusiasm and capabilities by drawing from existing competencies and other cities’ successes, as well as crowdsourcing public ideas and sharing resources and tools between sectors.

Planning Tools

Ensure high quality solutions by assessing risks, successes, and how land-use planning impacts water in the city. Model possible physical and socio-economic scenarios – as seen in Cape Town – to demystify plausible scenarios, guide next steps, and involve another degree of public participation.

Implementation Tools

A system of sustainable urban water hinges on equity, transparency, accountability, water quality, and well-maintained infrastructure. Write these into long-term plans. Innovation, integrated services, and adaptability is a must! Support this with new regulation that augments traditional and new public-private financing models and encourages (even small) frequent financial incentives.

Why the Principles Matter

The principles work thanks to the advent of a one-water concept: viewing “all water weathers”, and runoff, wastewater, greywater, potable supply, etc. as interconnected.

This standpoint was spawned as recently as the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, around the time that sustainable development emerged on the agenda and “the derivative concept of integrated urban water management arose”, Daniela explains.

Until then, water issues had been perceived as separate and solutions were disjointed.

Integrating water was held back by a disconnect between practitioners and researchers: “Most utility professionals don’t read journals,” Daniela reports. This she knows from 18 years of managing city stormwater services in Porto Alegre, Brazil. “We go to a conference once in a while, and that’s it.”

The IWA realised this prevented ground-breaking findings from filtering through to those who could actually use them.

Forming a steering committee to bridge the gap, the IWA translated valuable academic knowledge into simple language. Decision-makers and multiple stakeholders finally had the opportunity to grasp the knowhow and run with it. Eventually, this formed the principles.

Room for Improvement – The Fifth Circle

Let’s stress that the principals are guidance, not a definitive template. There’s no one-size-fits-all for any city.

Daniela also points out that the concentric model assumes that fundamental water supply and sanitation services are already in place. In the Global South especially, this is not always the case.

If you don’t have water to drink, if you have wastewater in your backyard, why are you going to be worried about climate change?

It’s a fair question.

That’s why the IWA is discussing adding an ‘inner-inner’ circle. This would supply the extra principles developing cities need to reach a baseline of water justice and establish the services that comply with the human rights of sanitation and water quality.

For now, these cities must continue to rely on their own initiative or, better still, look to others for lessons in what works – and what doesn’t.

This isn’t to say that the current principals are not applicable to developing nations. However, most will need to start at the centre – city infrastructure – and have a longer journey to complete.

Kampala, in Uganda, for example, used the model to improve flood management by identifying the need to expand their storm drain and pipe networks. On a community level, they combined this with greenery to beautify the streets, which minimises runoff. Most impressively, they deliver community-based workshops on waste management to keep citizens involved.

Nor is it right to dismiss the inner-circle scale for developed and economically prosperous cities.

The small, wealthy city state of Singapore, Daniela tells us, relies on imported water from neighbouring countries. But political tensions or a change in rainfall patterns could see the supply simply cut off.

Singapore is planning ahead, creating robustness in the form of diversifying water sources, including desalination and water recycling.

“So, although they have social and economic similarities to Nordic countries, for instance,” which are lauded as highly advanced in their handling of urban water, “the problem they face is related to the inner circle.”

If anything, this goes to show how applicable the principles can be for any city working to become more water-wise.

Further Reading

We have only touched on the details of IWA’s 17 principles here. For a more in-depth look at what’s involved in each, view the full text online.