Day Zero: the moment a city’s water dries up completely. For Cape Town, this deadly scenario came too close, but it was averted thanks to collective action and decisive leadership. This story serves as a get-started guide to conservation for any city wishing to turn the tides on water stress.

Patricia De Lille, now South Africa’s national Minister for Public Works and Infrastructure, was mayor of Cape Town when the usual winter rains failed to arrive two winters running.

Thankfully, the city of around 4 million people was ready. Dealing with a dry climate much of the time, Cape Town had implemented a Water Demand and Conservation Management Strategy 15 years prior, making the best use of the reserves it had. This even won the city an award for water efficiency.

But when drought’s dusty grip took hold in 2018, reservoirs dipped to 20% capacity. It was a crisis.

Keeping the water running required further action. How Cape Town managed it is a masterclass in managing water stress.

Don’t Wait for a Crisis

By October 2017, experts were confident the rains were just late. They would drop later that year. But they never came, and the reservoirs dried up.

“I can tell you with hindsight that you must never listen to people who are trying to predict the weather,” the minister tells us. “Climate change has made the weather unpredictable.”

As mayor, De Lille knew that she would be held responsible for whatever outcome. This motivated her urgency.

You can only save water while you have water.

Even so, given the chance again, she would react sooner: “I think 50% of a dam level should be a warning sign for everyone that you need to start acting now.”

Get Informed – Run the Data

Step one was to understand the extent of the challenge. “If you can’t measure something, you can’t manage it,” Minister De Lille muses.

The mayor enlisted help from specialist teams stationed at various dam systems. They monitored water levels, while the municipal water team measured how much the city consumed daily. Combined, this data was analysed to predict how long the reserves would last and determine the savings required to extend that cliff edge.

Plan for the Worst Case

With the problem spelt out, our CityChanger called on the wisdom of infrastructure and financing experts, senior city managers, and renowned scenario planner Clem Sunter to workshop plausible conservation options.

They considered worst- and best-case scenarios to develop a mitigation plan. This called for a holistic view of water systems: citizens, sanitation services, and industry all draw from the same water sources; to prevent Day Zero, all consumers have to make changes.

Be Honest with Stakeholders

City management prioritised cooperation over punitive measures. “I was hesitant in the beginning to put up the price of water,” Minister De Lille remembers, “because I wanted the community to buy in and help us to save the water.”

To rally people, the mayor chose not to sugarcoat the brutality of the situation.

Consumption limits were imposed: 800 million litres a day at first, declining to 600 and then 500 million litres as the drought raged on. Incremental deductions gave people time to adjust.

Daily updates were sent to everyone in the city. These were informed by critical reports given by the city’s senior management, the directors of Utilities and Water Services, and external experts in mitigation, building resilience, and water sources. They met seven days a week, at 07:00 am, for the duration of the crisis to gather intelligence that informed Capetonians “where things stood, what we were doing as the city leadership, and what we needed business and residents to do”.

The city developed visual aids, which became powerful communications tools, including:

- an online dashboard showing a virtual representation of water levels,

- a countdown to Day Zero at current consumption rates,

- an online water calculator to track household water usage.

With the city informed, the challenge shifted to defining what change should look like.

Act with the Future in Mind

Cape Town was crowned World Design Capital in 2014.

Learning from the previous incumbent, Helsinki, the city introduced design-led thinking and now incorporates climate change measures into all city planning and infrastructure decisions.

That led to diversifying water sources. Reliance on rainfall had caused this chaos! Bringing in multiple channels would mitigate future Day Zeroes.

Identify & Distinguish Water Sources

Dismissing a proposal for coastal desalination plants – due largely to the expense and time needed to test and construct the right system – the mayor looked to drought-prone California for inspiration.

With the help of satellite surveying, Cape Town discovered aquifers 50,000 metres underground, which they could exploit for non-potable purposes like the US state.

“The price of getting groundwater out is much cheaper than desalination,” the Minister reasons.

The city’s historic drainage system had always flushed stormwater straight out to sea. That represented a wasted resource! An infrastructure reform redirected this water to replenish the aquifers.

Additionally, the city’s singular reticulation system is gradually being converted into a duel system, separating potable H2O from treated wastewater. This way, fresh water is conserved for human consumption, while greywater serves sanitation services. Selling it to construction companies at a discounted rate has been a popular move.

However, this all called for widescale, long-term infrastructure overhaul. The immediacy of Cape Town’s problem required swift solutions – and public support.

Empower Stakeholders

The city launched an awareness campaign to encourage Capetonians to change their water consumption behaviours. This was a crucial step, and no chances were taken – an outside agency was brought in to lead the strategy.

It appealed to people because Patricia De Lille – as mayor but also as a citizen – became the face of the campaign. She was shown making personal sacrifices and practicing what she preached. This humanised it and bridged the void between the municipality and people.

To build trust in recycled water, for example, the mayor was shown drinking a glassful on site at a wastewater treatment plant.

Like many Capetonians, Minister De Lille had a six-metre home pool. “I decided to close it completely.” Not just during the crisis – completely! This served a strong political purpose: showing solidarity.

The city also led by example, ceasing with the irrigation of public parks, and closing municipal swimming pools.

In a master stroke, Cape Town trained 4,000 young jobseekers in simple plumbing and employed them to fix residents’ leaking taps, washers, and pipes. This army of water warriors helped reduce water loss from 14% to 11% in just two months.

Enlist Civil Action

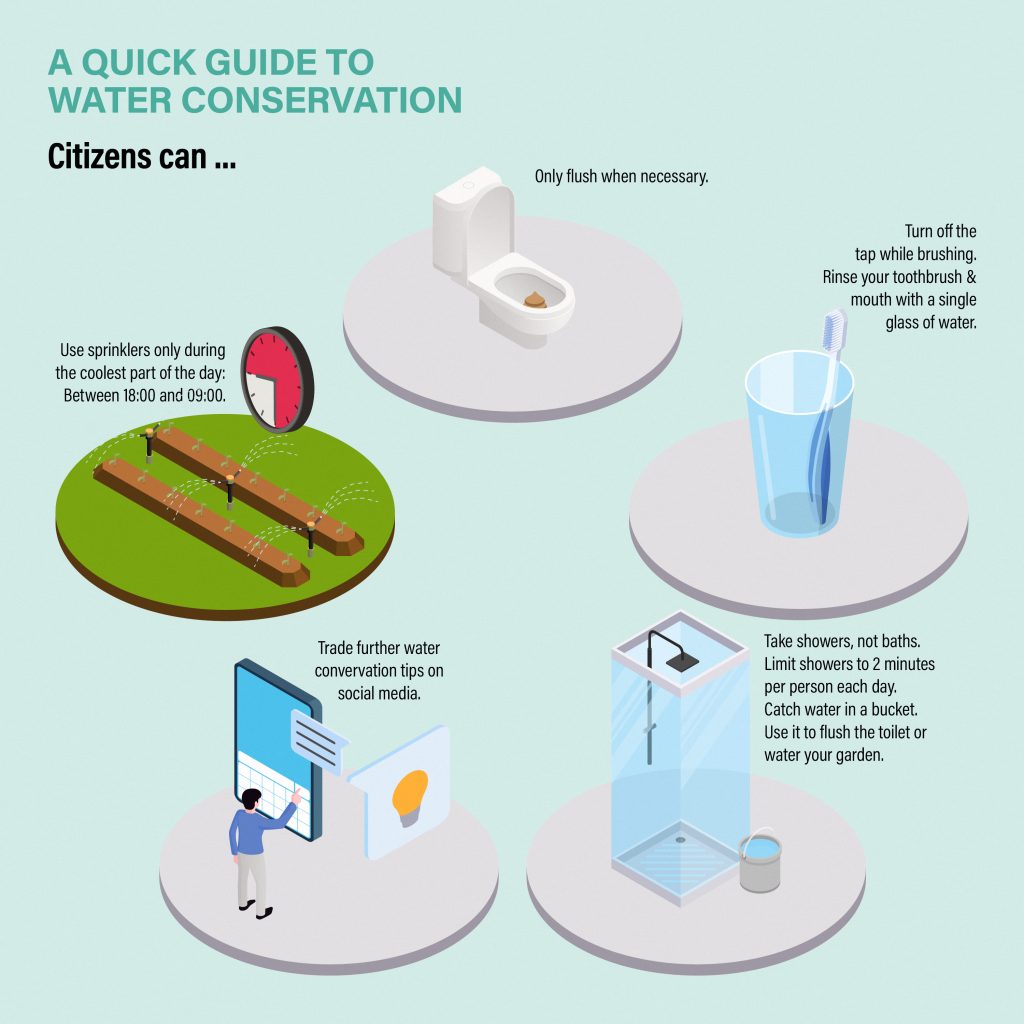

By the time water use was capped to 350 litres per day per person, many citizens were convinced of their role, but they still needed guidance as to how to conserve water.

Over the duration of the campaign, various rules and advice were issued.

.

Momentum increased. Collective daily water use dropped by 30%. The public took to social media to trade their own tips.

To assist residents to limit washing time each day, South African musicians re-recorded some of their best-known songs in two-minute versions.

Ask for Help

What resonated with the public, it seems, was asking – not telling – people what to do.

All stakeholders must be involved. It is not just a government thing. We should never claim that we know everything.

The mayor hosted a two-day exhibition at the International Convention Centre. “I invited communities and companies and design people to come up with ideas about how we can save and manage water. It was amazing!”

Each week innovative companies were given space – gratis – in shopping malls to showcase and sell their water-saving products. Water-wise Capetonian’s were snapping up “water tanks, waterless car wash products, tap aerators, and water efficient flushing and shower systems”.

Equal Enforcement

Eventually, the costs of water increased fourfold to help drive down waste. High-yield consumers were charged even more.

“It took a long time before people in affluent areas started saving water properly,” the Minister recalls. Fines were introduced for overconsumption. “When it started hitting their pockets, people started saving water in more significant amounts.”

In hindsight, the mayor would have raised tariffs and introduced fines sooner.

Some citizens needed more persuasion still.

What may seem a heavy-handed move reflects the severity of the situation: persistent offenders were publicly named and shamed.

The mayor personally visited these households with the media in tow to document practitioners swapping out their water meters – which belong to the city – for one that limits water flow to 350 litres per day per person.

Some landowners attempted to get around quotas by drilling boreholes to extract underground water. Not suitable for drinking, they used this for irrigating gardens. It risked forming sinkholes, the Minister reports, so permanent regulation and monitoring were introduced to limit the number of permits and track water levels.

Public & Private Responsibility

Local businesses, too, were expected to make concerted efforts to reduce their water use.

Nevermore was this demonstrated than by the reaction to a well-known blogger bragging on social media about lazing in a full bathtub at a luxury hotel.

The mayor marched in and calmly told the management that their guests must follow the same steps as everyone else. She also handed them a pile of buckets – to collect the bathwater for flushing their toilets.

The hotel went a step further and now has a system in place to redirect and reuse greywater.

Under Patricia De Lille’s custodianship as Minister for Public Works and Infrastructure, South Africa has begun a programme to replicate this by refurbishing water systems in public buildings.

And unless the landlords from whom the municipality rents offices make efforts to ‘green’ their buildings, the city will make good on their threats to find alternative premises.

Those who introduce efficiencies save the municipality money, which they split with landlords to help recoup their investment.

Mitigating Day Zero in a Nutshell

The rains returned to Cape Town in 2019 and soaked the parched ground of the city’s reservoirs. But, until they were saturated and started refilling, the restrictions had to stay in place. They were gradually lifted in November the next year.

Cape Town was able to retain enough water until the rains returned because of a mix of bottom-up and top-down short- and long-term responses, incentives, and penalties. Ultimately, however, what kept the taps on was the combined efforts of all Capetonians.

By being an honest and realistic leader who led by example, and by expressing the urgency before it truly became a crisis, now Minister De Lille led a response that averted catastrophe. So we’ll leave the final words of advice to the CityChanger herself:

“Plan, design and implement all projects factoring in the impact of climate change. It is real and it is devastating, and it is unpredictable. In the face of crisis, be bold, be innovative, act now, and collaborate with stakeholders to get the job done quicker.”

And for more guidance on how to avoid Day Zero, check out this guide published by Unicef.