Finance is an unavoidable puzzle piece in making cities sustainable. With scaling a priority, leveraging enough money is a challenge. Too often, if forces us to focus on a single objective, when what we need for meeting climate targets is holistic change. Rufus Grantham speaks with CityChangers to offer his guidance for attracting millions in investment – and says it’s easier than we’d assume. Not only that, but approaching with an unconventional perspectives can turn that initial cash injection into an inexhaustible financial resource.

Many CityChangers tell us that we already have a lot of solutions that could help overcome urgent urban challenges. If that’s true, they’re clearly not being applied fast enough or to the scale necessary. That’s often a financing issue.

James Hooton from the Green Finance Institute told us that there is enough money out there to pay for greener, fairer cities. It’s just not (yet) invested appropriately. And in her book, “The Gendered City”, Nourhan Bassam explains that this is “inherent logic” in an economic system that “prioritizes capital accumulation over human well-being and environmental sustainability”.

How can convince those with sizeable assets to marry the money with initiatives promising impact?

Turning around a long-established financial system seems a Sisyphean task. It’s going to take a well of perseverance and a whole lot of fiscal know-how. Rufus Grantham has both.

He’s in the Money

Our CityChanger is a former financier, twenty-plus years into an “accidental” career in the banking sector.

As a directionless psychology and neurophysiology graduate, Rufus was advised to take an accountancy qualification and joined PwC, “one of the big six” financial bodies.

With that on your CV, people listen. Rufus became an equity research analyst and got to speak to high-profile business bods (senior management, CEOs, CFOs) and use that info to “build a financial model to say what that company is worth. He’d then tell investors whether it’s cheap or expensive” to stake their wealth against it. Basically, Rufus was evaluating return on investment (ROI).

It was interesting work but the end goal was always the same: making shareholders a little richer – including those of large, faceless global conglomerates. “At the end of the day it’s relatively meaningless,” he tells us.

Then came the 2008 financial crisis. At the time, Rufus worked for Lehman Brothers – a “challenging” time, he comments wryly. A few years later, while managing an under-resourced department of almost 100 people with a $30 million budget, burnout came calling.

The day he was made redundant, Rufus recalls, “my immediate physical response was relief. And I thought, that probably tells me I might not be in the right place”.

Bankers Without Boundaries

By this time, Rufus had children. He cared about the planet they live in – and pondered what his role in that might be.

From the inside, much of the financial sector didn’t seem to work to make the world a better place. Although, some organisations integrated sustainability in their investment decisions.

Now, though, a new concept was emerging: investing for sustainability impact.

IFSI sees wealth managers put their money in activities that actively “address sustainability challenges”, the UN Environmental Programme[i] reports. Rufus adds that it’s a mechanism for “connecting the outcomes of projects with the funding required to do it”.

If we can make that link clear to ethical investors, the finance bit will flow easily, he claims.

Growing evidence suggests that this more purposeful investing is what many individual investors want from those managing their investments.

UN Environmental Programme

That’s very much the idea behind Bankers Without Boundaries (BWB). This not-for-profit group provides wealth management and advice for investors wanting to build portfolios that have beneficial social and environment impacts. Determined to make a difference, Rufus began volunteering with them.

Breaking Convention: Creating Continuation Funds Via Cost-savings

Within his first week with BWB, and little clue as to the ins-and-outs of the sustainability world, Rufus was in Belgium holding imposter syndrome at bay.

His (more experienced) colleague was explaining to Leuven’s finance, sustainability, transport, housing, and planning teams the challenges involved in turning a city Net Zero. Rufus felt out of his depth. But he saw something they didn’t.

“What struck me was that the thinking in the public sector about finance is predominantly focused on a finite budget.” They have to prioritise how to spend the sum they’re allocated because when it’s gone, it’s gone.

Rufus realised that a bit of clever forward planning could see cities develop an almost inexhaustible pot to fund their projects.

Example 1: Electrification of Public Transport

A step for Leuven to become Net Zero was the electrification of the public bus service.

Electric busses are cheaper to run than those propelled by fossil fuels. And if claims are to be believed, because these vehicles have fewer moving parts, EVs are also cheaper to maintain.

So, there’s a cost-saving. Even taking into account the expense of retraining personnel in e-bus repairs.

Except, we still need to buy the vehicles. That’s a major outgoing, which the municipal budget won’t stretch to. The only option is to borrow, but how can cash-strapped councils justify such huge debts? Usually these have to be paid back by the taxpayer.

Step 1: Don’t pass on the cost-savings. Keeping charges the same.

If bus tickets cost the same as before but expenses drop, the city generates a surplus without increasing taxes. That can be used to pay off the debt. When the debt is paid, that surplus can be reinvested elsewhere.

Sure, the investor is making a profit, but they’re also happy about making a positive impact – as per IFSI principals.

Example 2: Retrofitting

Rufus describes this system as “applying financial-first principles and investment return structures to net zero related projects”. The same idea can apply to almost any Net Zero that leads to a cost-saving via improved energy efficiency.

The UK has a target for all homes to meet Environmental Protection Certificate band C by 2025. “But only 29 per cent of homes today meet this standard,” writes the Green Alliance, and business-as-usual will see emissions targets fall short by 40% by the deadline.

Retrofitting is sorely needed. But like EVs, double glazed windows, insulation, and heat pumps are expensive.

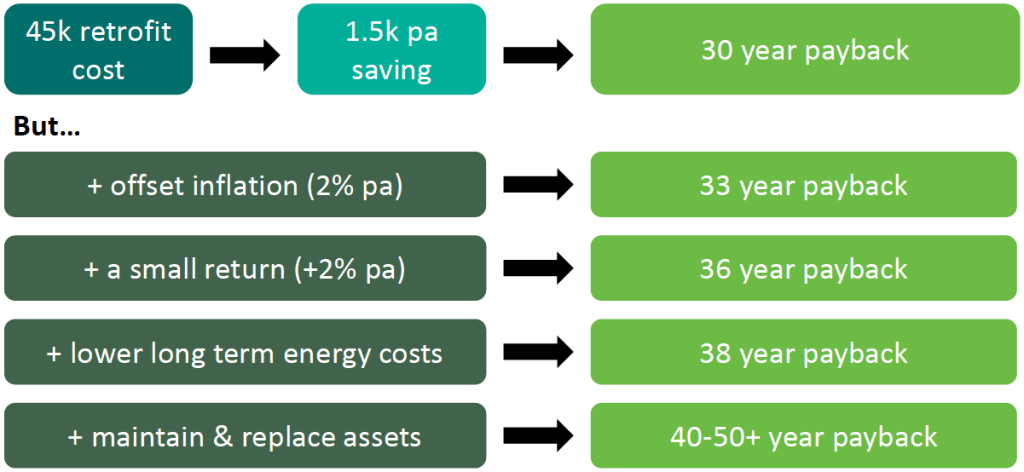

Rufus suggests a full deep retrofit could average around £50,000 per household. A loan of that size – such as a green mortgage – is difficult for individual households to pay back. The rates they pay are usually much higher than the amount they save by cutting energy bills – especially as extra costs accumulate over time. Given that “the average UK household homeowner is 56 years old”, a 25- or 50-year debt is likely out of the question anyway.

Are we really thinking we can get tens of millions of householders in a country to go to their bank, borrow £50,000 pounds, and undertake a really complicated technical task in order to be out of pocket? It doesn’t add up.

Public subsidies haven’t helped much. Up until it was withdrawn in March 2021, the UK’s Green Homes Grant would only cover half of the costs, up to a measly £5,000.

Ethical investors have their hands on a lot more – and they’re willing to share.

The Retrofit Doorstep Challenge

There’s another barrier, though: “People won’t let you in their houses”.

Retrofitting is dirty work and a lack of awareness for non-financial gains – comfort and quality of living – stand in the way.

Engaging residents is an artform. Rufus suggests we stop talking of technicalities like heat pumps and climate change, and instead address people’s personal needs.

Or we could show them what they stand to gain. Jeff Colley of Passive House+ suggests councils start by retrofitting the empty units in their social housing stock. Tenants can then move in temporarily for a “retrofit holiday” while their homes are renovated.

Whether this is an option or not, Rufus says plans need to factor in financial incentives to encourage households to participate. A rebate of, say, £300 rebate each year should be enough to get them to open the door.

The Name’s Bonds, Green Bonds

Unlike a single public transport network, retrofitting will be a long ongoing process. We need to act at scale: almost 70% of the UK’s 28 million residential properties need to be retrofitted.

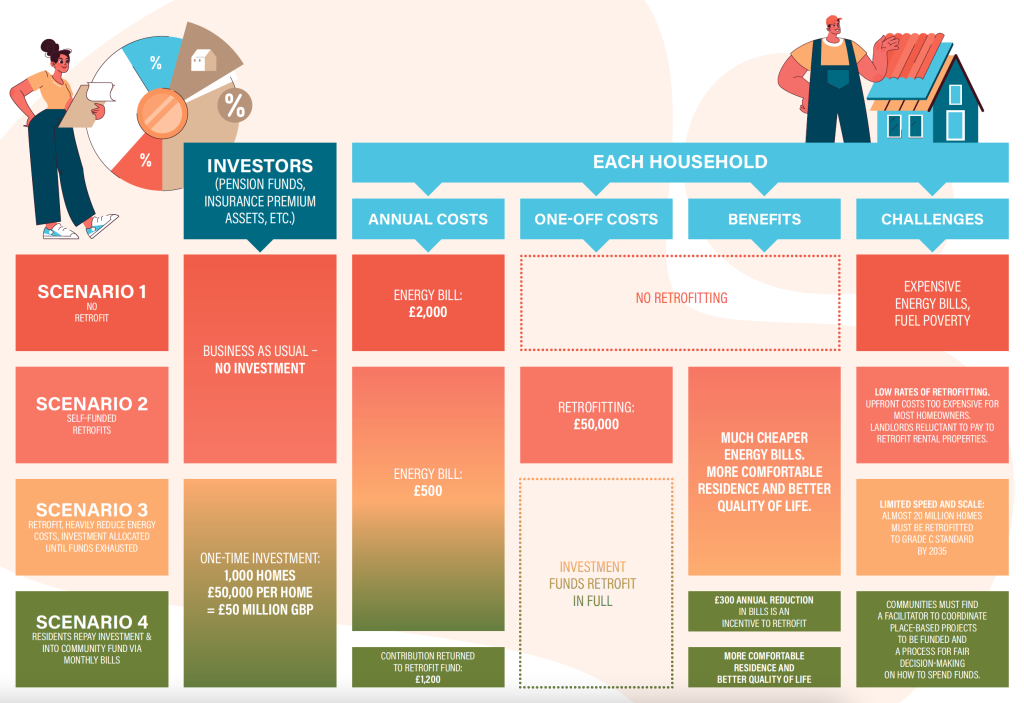

Managers of pension funds and insurance premiums handle the kind of cash reserves that match this magnitude.

They want good investment opportunities that offer steady, secure growth to meet their long-term liabilities – and turn a profit. It’s called asset liability matching.

In fact, those who deal in billions are only interested in investing considerable sums. The returns on a mere £50,000 to retrofit a single home are insignificantly miniscule. Give them 2,000 homes, however, and the potential for ROI accruing over 40 or 50 years will be heavily persuasive.

When the work is done, we can continue to charge residents close to what they previously paid (a ‘comfort fee’), and still via utility bills. The annual rebate makes it worth their while. But as energy use is reduced, and costs lower, we get a ‘cash surplus’ – similar to Leuven’s bus fleet.

At first, that surplus will pay the investor. Then what?

The Bigger Picture – And How to Fund It

Rufus recommends we put that extra cash in to a community fund. In fact, get the costings right and we can start paying into it from the very beginning (see examples of possible scenarios in the graphic below).

This is the idea behind Living Places, a UK-based advisory group specialising in investment for holistic sustainable solutions, which Rufus set up in 2023.

The multidisciplinary team are provoking community-wide improvement using these financial levers to fund place-based initiatives.

“We started thinking, well, you could re-green streets, you could put in EV charging infrastructure, you could install secure bike storage so that people can take active travel options…”

Maybe they want lighting for a dark alleyway where people are afraid to walk at night. Or repair part of a pavement that floods regularly, making access difficult, especially for those in the street with limited mobility.

But to really grab investors’ attention, we have to stop thinking in terms of a single idea.

Green Neighbourhoods as a Service

Similar to retrofitting, scale is important for attracting investment into a community.

So, Rufus is in the process of bringing together entire neighbourhoods to work together as a kind of consortium. That can include homeowners, public buildings, businesses, as well as private and social landlords and their tenants.

Whether independently or with the help of a facilitator, it’s up to the residents to identify the changes they want to see. Then Rufus can go to ethical investors and inform them that their money could change not only every home on the street but the street itself.

It’s a concept our CityChanger first wrote about in an article titled ‘Green Neighbourhoods as a Service’ (GNaaS). “It’s terrible branding,” he jokes, but it was the blueprint for this approach to financing holistic, comprehensive urban initiatives.

That fund, Rufus explains acts “almost like a collective insurance scheme,” paying for maintenance, repairs, and replacements, for example. Plus any legal and facilitators fees.

As time goes by, the community might identify new needs, or get even more creative. Possibilities are endless, but he suggests they could:

- give it back to households as an additional energy bill rebate

- set up a community education fund to give bursaries to kids going to university

- start an apprentice scheme to provide new work opportunities

- use it to augment the green infrastructure in that place

- support small businesses that are going to provide services to the community

- subsidise a local shop.

You may notice that, by this time, we’re not even asking where the money comes from. That’s because, surprisingly, attracting even millions in funding is the easy part.

Next Steps

Rufus is bothered by two things: taking action and working to scale.

“But the frustration is we haven’t actually done it yet. We’re still at the business case preparation phase, not the not the delivery phase.”

I don’t want to write any more reports about it. Because it’s driving me mad, we need to actually get projects going.

It’s a complex process. And citizens, decision-makers, and investors are rightfully weary of new, untested ideas.

Demonstrator communities, he believes, will help motivate cities to rally their citizens around the idea of neighbourhood consortiums. Investment will pretty much fall in to place.

The Living Places team is already in talks with plenty of municipalities to activate “a cohort of places to work together on a series of demonstrators” either at a regional or national scale: Manchester and Hounslow, London, UK; Copenhagen, Denmark; and groups of cities in Poland, Italy, and Spain are also considering it.

“I think we’re slowly getting there. But it’s difficult.”

Part of the reason that Rufus is keen to get stuck in is because he knows there will be teething troubles. Nailing the best solutions will be an iterative process, so it’s important to get started as early as possible.

Even so, our CityChanger is happy to have initiated dialogue around grand-scale investment, and to bring attention to a realistic and sustainable way to fund place-based change. Now he concludes, it’s time to act. And we must act together.

[i] Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, A legal framework for impact – sustainability impact in investor decision making, report commissioned by UNEP FI, The Generation Foundation and PRI, 2021.