Retrofitting Europe’s built environment would drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions and position us closer to climate goals. It’s a tantalisingly tangible but costly outlook, and progress is slow. To change this, the Green Finance Institute (GFI) set itself the task of creating conditions where finance is instead a driving force. Now, with a proven track record, the GFI is venturing into Europe. Let’s explore how they’re making money talk where it matters and what it takes to replicate the ideas that actually work across borders.

The built environment is a major source of greenhouse emissions because of poor energy efficiency performance. Overall, Europe needs to reduce building-related emissions by 55% by 2030 to stay on track with climate targets. With 87% of Europe’s built environment predicted to still be in use in 2050, we desperately need to change the nature of what we already have in place. Retrofitting offers a way to decarbonise and turn them into more habitable and eco-friendly properties.

But achieving the ambitions of the EU’s Renovation Wave requires change at scale and speed. The annual rate of deep retrofits in Europe currently stands at just 0.2%. The Buildings Performance Institute Europe tells us that this needs to increase to 3% “[i]f the EU is to achieve both its 2030 climate target and climate neutrality by 2050”.

Given the urgency, why are retrofitting rates so low?

The Financial Barriers to Retrofitting

We spoke to James Hooton from the Green Finance Institute (GFI) in his role as Managing Director of GFI Europe.

Having previously worked for Goldman Sachs in Europe and Asia, James knows that finance professionals are driven by fiduciary duty and making returns for their clients. Green investments, therefore, need to match the same level of risk-return as clients’ existing profiles. Up until now, this has rarely been the case.

According to James, one of the reasons for lack of progress in decarbonising the built environment is largely down to perspective.

There’s a persistent focus on return on investment – or ‘payback period’ – meaning that if the occupant isn’t set to quickly see a cash saving on their energy bills, they may be reluctant to meet the upfront costs of retrofits.

So, James says, we need a narrative that makes people realise the benefits of upgrading their properties. The GFI saw the potential for finances to be used as leverage for raising this kind of awareness and propelling action forward.

Finances too often come at the end of the conversation. If you can bring it much further forward, then it can have that catalytic effect or lever in the right project.

Plugging the Investment Gap

The European Commission estimates that achieving the ambitions of the Retrofit Wave would cost around €275 billion in additional investment in building renovation every year. In the UK alone – where the GFI originated – it would require about £360 billion to upgrade the 29 million homes and other buildings that need it by 2050.

Data from the Climate Action Network, James points out, suggests that if this hefty sum was actually invested appropriately, we stand to gain 291 billion Euros in terms of “economic, social, governance, and health benefits” – the ROI “is bigger than the European investment gap”.

The benefits he refers to include a reduction in damp and mould, a real threat to residents’ health. This would significantly reduce the estimated costs to the National Health Service of treating people impacted by poor housing, which currently stands at £1.4 billion a year.

Plus, research by PwC suggests that making homes more energy efficient could support more than 500,000 jobs in the UK alone. There’s a convincing business case to the Retrofit Wave.

“The capital is absolutely there,” James tells us. But to make it effective, we must create an enabling environment.

That calls for a long-term market that consists not only of input from policymakers but so about creating “the right sort of returns and the commerciality” to activate support from the private sector.

“This means making sure that financial solutions are in place to support the customers and businesses looking to make energy efficiency upgrades at pace and scale required.” And it’s exactly what the Green Finance Institute is doing.

Activating Relevant Actors

Thanks to support from Laudes Foundation, the GFI is financially independent and therefore not a competitor for funds.

Being seen as a neutral facilitator by other organisations was essential for establishing the Coalition for the Energy Efficiency of Buildings (CEEB), which convened more than 400 built environment stakeholders to share their knowledge of the challenges in the retrofitting workflow. This, they discovered, include:

- high upfront retrofitting costs

- disruption to residents while the work is underway

- a general lack of public awareness of the benefits

- high interest rates

- the cost-of-living crisis.

With this knowledge under their belt and realising that new practices wouldn’t come into being unless someone with their impartiality would take the lead, the GFI set out to scale existing and develop new financial products.

Green Finance Institute – UK Success Stories

The GFI now has a number of impactful products and ventures, including a Green Mortgage campaign, which has helped scale the UK’s green mortgage market to more than 60 products – having grown from just three initially.

They have also advised individual cities on large-scale projects. The GFI was instrumental to creating the London Climate Finance Facility, to which the Greater London Authority has committed £500 million for net zero projects. It’s reminiscent of Bristol City Leap, a public-private partnership that seems to be the example poised for replication these days, having created confidence for private investors to jump on board. There’s hope that London will soon see the same.

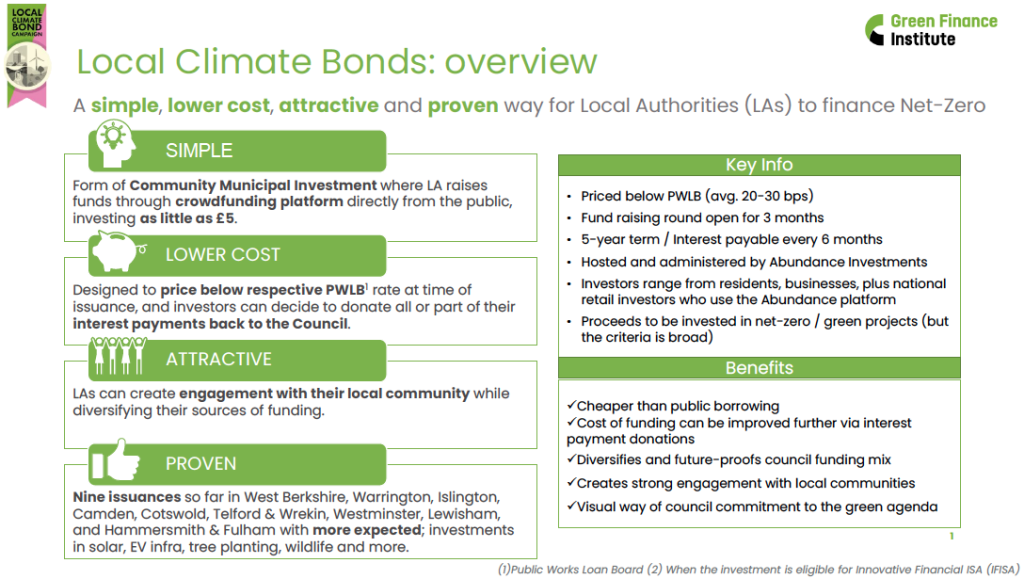

The kinds of projects that these investments enable are similar to another of GFI’s successful products: Local Climate Bonds.

Local authorities issue a type of community-municipal investment, via a crowdfunding platform, to fund local, net-zero projects. It’s a low-risk venture for the authority while creating opportunities to engage with local residents.

Nine UK councils have already participated, raising more than £6 million for initiatives such as installing solar panels and EV charging stations, LED lighting, retrofits, and even rewilding schemes.

The beauty is that investors can donate as little as £5 and expect to receive interest on their contributions. In London, where £1 million was raised in support for the Islington Greener Futures programme, 21% of the capital originated from the local community.

For us, it’s about how you use finances for a catalytic effect that actually serves the public good, and to do it in a way that the financial pot doesn’t run out.

Other cities can follow in their footsteps, thanks to the simple steps in the GFI’s Local Climate Bond toolkit.

Lessons from Europe

Despite these wins, the challenges of scaling retrofitting persist.

The European market is even bigger and attempts by other countries at similar concepts haven’t necessarily taken hold.

There was Italy’s Superbonus 110 scheme, for example. Also known as the Ecobonus, the government offered a 110% incentive on expenditure for residential energy efficiency upgrades. Its popularity exceeded expectations, leading the authorities to overhaul the scheme in order that it could be better managed as a revamped, more sustainable version.

Then there was the EU version of the Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) programme, in which the US pumped almost $14 billion into energy efficiency upgrades. Europace was funded by Horizon but failed to grow in European countries like Spain, James explains.

What Europe really needs, the GFI recognised, is a joined-up approach. After all, climate change doesn’t respect boundaries and Europe has a lot of retrofitting to do.

In response, and with support from Laudes Foundation, GFI Europe launched in October 2023.

GFI Europe – Challenges, Scaling & Sharing

Eduardo Brunet and Signe Fosgaard were appointed to GFI’s newest roles: as directors in Spain and Denmark, respectively. These are the first carefully chosen locations where there’s “a GFI-shaped hole” and local partners willing to work with them have been identified.

Signe and Eduardo are tasked with creating long-term plans for cashflow (generating investment needed to support initiative) and an enabling environment in these territories. They need to set up testbeds to see what works on the ground under local conditions. This knowledge, theoretically, can then be transferred from one country to another to plug what James calls the “execution gap” and accelerate change. The team hope that the public-private-partnerships like those seen in London and Bristol will find roots in Madrid and Copenhagen.

That means GFI Europe also needs “to work through the legal frameworks” of rolling out pilots between territories, he adds. Even within the EU, differences can complicate matters.

In Denmark, for example, legislation prevents property owners borrowing for retrofitting. Instead, they have to rely on public funding that is accessible only once the building requires renovation. And so, a scheme that works in Spain may not serve as an oven-ready solution elsewhere.

But plenty will. And by working out who can act as the local counterparty for new forms of financing, GFI Europe will establish these mechanisms as a major part of decarbonisation ‘business plans’. James is keen to work closely with the European Commissions to figure out the details of this: how to create the business case for sustainable finance and how to link it to industry. Answering these kinds of questions are the next steps to the scaling that is predicted to really take hold.

When you’re buying a house, you’re the counterparty for the bank. When you’re trying to decarbonise a city’s subway system, who owns the subway system, who’s actually going to borrow the money to make all the lights LEDs, etc.?

GFI’s Ongoing Impact

The clear message is that getting this right isn’t about having one winning idea. The Green Finance Institute – in the UK and now across Europe – promotes prototyping, adaptation, and diversification of financial products so that they suit local environments – financial and physical.

So, while GFI currently appears to be the partner Europe needs to fill the execution gap, it’s not the products but the impact they have on decarbonising the built environment that will prove to be the team’s legacy.

This article is produced in collaboration with the contributors as part of Laudes Foundation‘s support for the 2023 Urban Future conference.