The recent research conducted in response to JPI Urban Europe’s Urban Migration call offers a greater understanding of what the arrival of new populations means for the functioning of European cities, and what forces shape their experiences. It also provides new insights into what is being done to support arrival and integration processes in urban areas. Dissemination of these learnings should help municipalities strengthen their knowledge and provision, and pave the way towards new solutions. What follows is a synthesis of these findings, which are available in full in the comprehensive reports available online.

What is Integration?

Rinus Penninx broadly defines integration as “the process of becoming an accepted part of society”. Cohesion is constantly in flux as urban populations ebb and flow. This is why, even where it has occurred for centuries, migration is still a subject for debate and why we have not yet found a foolproof way of helping every newcomer find their place in a city’s social and cultural fabric.

A major contributor to this is the numerous and complex challenges and barriers facing different groups of migrants. Trying to become ‘like the locals’ seems an intuitive and desirable workaround.

But Melissa Fernández Arrigoitia warns us against misconstruing the idea of integration as “having to become like someone else, in order to fit a mould”.

Her project, MICOLL, addressed the barriers to quality and affordable housing migrants experience, especially as refugees. It was one of eight projects that researched what influence migrants have on destination communities, and vice versa.

Evidence from this exercise confirms how integration is a multi-dimensional concept, including the:

- sense of belonging

- physical places and/or communities migrants arrive and settle in

- unfettered access to essential services needed to lead a fulfilling life

- cultural citizenship of a new city

- feeling of being involved in a team or community

- chance to contribute a skill, activity, or service deemed to have value.

Any and all of these can help overcome alienation. As the Institute for Research into Superdiversity (IRiS) writes: “Migrants repeatedly express the desire to contribute and be accepted”, which is why restrictions to work can bring about feelings of detachment.

Why Does Integration Matter?

So cities need to understand that integration has to be baked in to “several domains or policy areas, including employment, education, social inclusion and citizenship”, the EMPOWER team writes. They looked into the impact that community-led infrastructure and place-making strategies in superdiverse neighbourhoods have on female residents’ sense of place.

But why should cities bother?

First, for asylum seekers, European countries have a duty to offer sanctuary as signed up members of the 1967 protocol of the Refugee Convention.

But a toxic political environment – supported by hostile policies and tight immigration control – has arisen in recent decades in response to waves of newcomers seeking sanctuary. Migration is effectively being criminalised, as those fleeing persecution are demonised as morally inferior, socially corrupt, and a drain on resources.

“The authorities are basically making their life as difficult as possible, so they won’t want to stay,” Jonathan Rock Rokem tells us. He represents MAPURBAN, a project which sets out to identify ways to improve migrants’ access to essential urban resources and participation in society.

What This Means for the City

While this hostility may be true of national policy, cities are typically expected to develop their own targeted integration strategies that meet the needs of communities at a local level.

Large historic cities like London are built on immigration. They have pre-existing migrant communities and the size and diversity of populations to absorb newcomers. This may be why researchers found them to be generally welcoming.

Even so, there’s widespread evidence that migrants are still excluded from essential services.

Exclusionary policy makes life hard for new arrivals. It can lead to migrants going without housing, financial aid, healthcare, education, and all manner of other services that resident citizens take for granted. It can even block them from learning the local language if courses are off limits.

These exclusions can lead to situations that require other interventions, such as:

- homelessness services for rough sleepers

- legal or medical support for victims of domestic violence (who are often denied spaces at shelters)

- legal proceeding, that could have been avoided if migrants were not reluctant to act as witnesses

- healthcare for diseases that could have been prevented with child inoculations.

We can also surmise that any working days lost to these issues only add to the financial strain.

Therefore, decision-makers should seek to construct a welcoming environment as part of their policy goals. This is a responsibility that cities have for the wider community and is beneficial for welfare and life chances of the migrants they embrace.

Healthier urban spaces are consistently those with signs of social integration amongst all people living there.

Melissa Fernández Arrigoitia, MICOLL

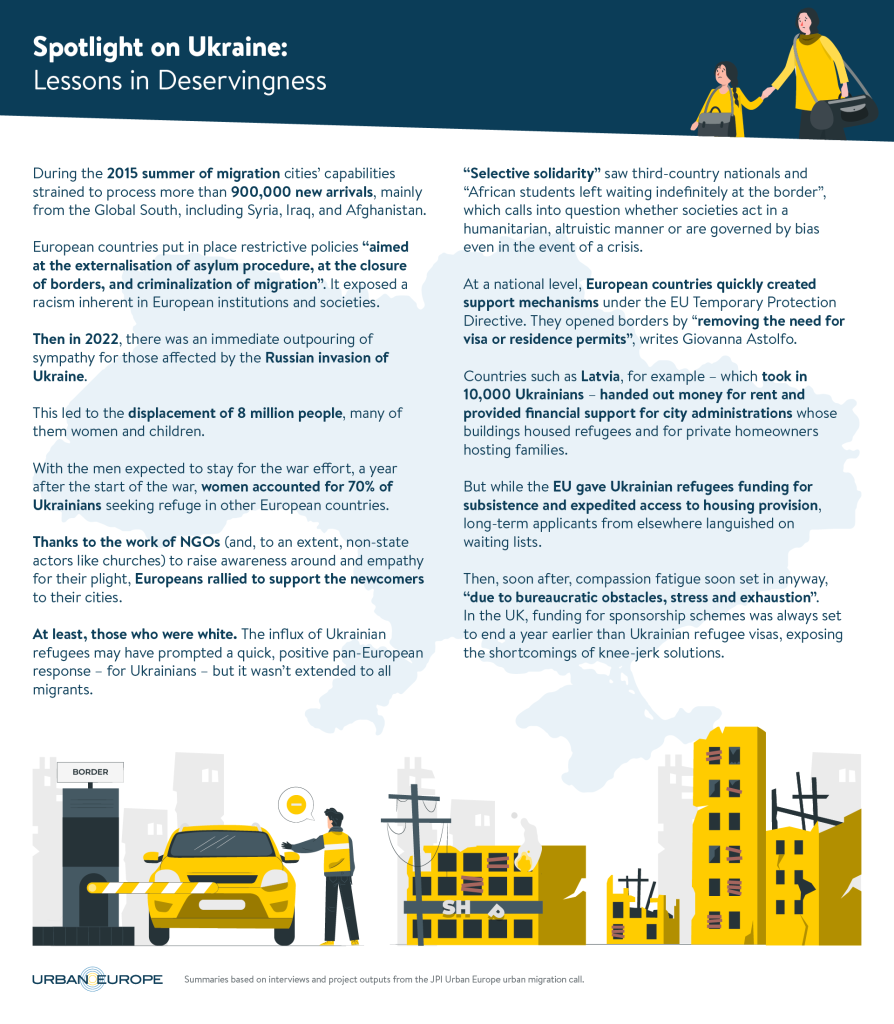

The Europe-wide solidarity shown to refugees arriving from Ukraine in 2022 is an eye-opening case study in how to get this welcoming environment right and wrong simultaneously. It provides many lessons for future crisis management – the most notable being the need to combine an urgent response and long-term planning.

How Cities Promote Integration

Host cities must nurture migrants’ experiences along spatial and relational dimensions to help them feel welcome and included. They need to look beyond simply what money they can throw at a situation to meet fundamental human rights and migration laws in the most rudimentary way possible. Rather, authorities must offer chances for migrants to build social capital – meaningful connections with local people and places.

In the research, forced migrants who had access to stable accommodation rather than being stuck in temporary shelters or hotels reported feeling quite settled. Permanent housing contracts give people time to build relationships within neighbourhoods. Innovative housing models, like collaborative housing, enhance social mixing, which combats the loneliness that is common among migrants coping with isolation.

That’s why cities that offer access to affordable housing are also supporting migrants’ root-making processes.

Arrival Infrastructure

Then there’s the arrival infrastructure. This refers to the public urban resources that are essential to the integration process. EMPOWER’s report states that arrival infrastructures include “a variety of housing typologies (including asylum centres or squatting), shops as information hubs, religious sites, facilities for language classes, hairdressers, restaurants, transnational networks and call centres”.

MAPURBAN takes this a step further. They found that new arrivals gain some of their ‘right to the city’ from public transport, which is a means to reaching resources and amenities. As a public arena in its own right, public transport also provides a place for chance social encounters and therefore for forming connections. Other public spaces do too, like parks, streets, town squares, churches, cafes, and sport facilities, where newcomers get to mingle with other diverse populations.

Solidarity & Sharing

What stands out about these places is their similarity to those that proved significant to sharing practices in the ProSHARE study. This project focused on non-commercial sharing, asking what forms it takes in socially mixed neighborhoods, and what conditions influence it.

So while “the most important place for sharing is … one’s own house”, social contacts are the primary motivator. That’s why the locations mentioned above are popular hubs for sharing “activities, help, and information”. They’re also spaces of solidarity that bring communities together on common grounds for peer-to-peer support: almost 40% of survey respondents in the Hustadt area of Bochum, Germany, reported getting help from people in their (superdiverse) neighbourhood.

Cultures of Solidarity

Sharing practices were found to help communities fend off threats of gentrification, too. It is therefore in municipalities’ interests to promote these activities as a way to protect affordable and social housing stock.

But besides creating easy-access infrastructure and a supportive community, having a common denominator can also be integral to a newcomers’ sense of belonging and social integration.

Known as a ‘culture of solidarity’, familiar factors that metaphorically connect people are enablers – they aid newcomers in accessing informal support structures and navigating language barriers.

“Religion and faith have a special social significance,” the MAPURBAN report confirms. So too does food and other such indicators of cultural identity.

The significance of conviviality in these relationships must not be understated. Celebrations such as weddings and public events during holidays and religious festivals are important to feeling part of a community.

Fair Social Spaces

Unfortunately, there’s not always room for conviviality in marginalised people’s priorities.

‘Fun’ is less important than finding a place to live, an income, schools, bank account, a doctor, childcare, etc. This pushes some people to disengage from recreational activities. But leisure time is important to wellbeing.

As that’s also a public health priority, cities should act. They can exploit quick wins by improving access to green areas, sports facilities, and other grounds for recreation with low barriers for use.

These spaces also offer possibilities for interaction, and not only with other migrants. Diverse social mixing sounds like a pretty good sign of integration.

What Cities Should Do Next

Where these mechanisms are not yet present, or where they are not well known, cities can facilitate their creation and visibility through funding, promotion via (multilingual) communication, and by connecting local actors who share an interest in migrant integration, planning, and policy.

And as improvements to infrastructure benefit the general population, the investment is a political and socio-economic win.

For a more comprehensive look at what can be done to understand local conditions and to improve the arrival and integration experience, visit our guidance on tools and recommendations for policies and urban transformation mechanisms.

Note: This article is commissioned by and produced in collaboration with JPI Urban Europe, a European research and innovation hub founded in 2010. JPI Urban Europe funds projects which address pertinent global urban challenges. Between January 2021 and January 2023, their support enabled eight projects to explore the concepts of urban migration and integration. CityChangers.org has partnered with JPI Urban Europe to make the findings of these research projects more tangible and accessible to a wider audience. More details about the Urban Migration call can be found on the JPI Urban Europe website. The original version of this article is published here.