The electric car revolution is already underway on a global scale. Everywhere we look we are told that electric vehicles are green vehicles. But should we really be including ‘clean vehicle’ infrastructure in future plans for our cities’ urban landscape, or is this battery-powered solution just a dead-end road?

There are many benefits to swapping from fossil fuel-powered vehicles to electric ones – and it’s true that they will help when it comes to reducing levels of pollution, but maybe we should think twice about whether or not they really are the silver bullet solution to our emission enigmas before we redesign our cities to accommodate them, and what the better alternatives might be.

Framing the Problem

The first thing to mention is that the demand for electric vehicles is increasing… and it’s happening rapidly. Deloitte predicts that by 2030 there will be 21 million electric vehicles on the roads – a huge jump from the 2 million sold in 2018. Likewise, a recent study from the universities of Exeter, Cambridge, and Nijmegen predicts that by 2050 every second car on the streets of the world could be electric.

The second thing to note is that this same study shows that the average ‘lifetime’ emissions from electric cars, including those generated from their manufacturing, are up to 70% lower than the average EU petrol car. They will help in the fight to increase urban air quality – but while they may be a move in the right direction, they are not necessarily sufficient on their own to create liveable cities.

Why? Because air quality is only one of the problems we’re facing in modern cities today. The problem with concentrating only on electric car infrastructure is that it does not increase city life, encourage more active lifestyles, improve cityscapes nor decrease traffic congestion.

A parliamentary select Committee’s report by Professors Phil Goodwin and Jillian Annable hits the nail on the head about what the real problem is about moving only in the direction of electric infrastructure investment: “The uptake of electric cars is likely to put upward pressure on traffic growth by lowering the costs of motoring. Clean growth means considering the combined effects of continued car dependency – which leads to more urban sprawl, inactive lifestyles, and congestion together with the lifestyle impacts of vehicles and batteries, charging infrastructure and car-parking capacities.”

But even if all of the cars on our streets became electric tomorrow, we would also still be faced with what is perhaps the most fundamental problem of all:

Space, Space, Space!

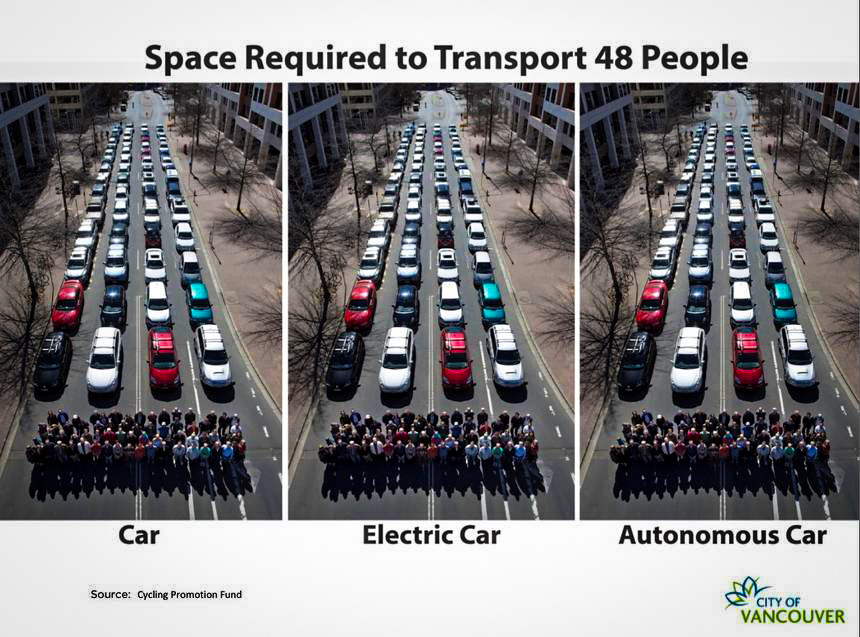

Space is the most valuable resource in any dense urban area, and while the engine may be different, at the end of the day an electric car is still a car. No matter if it runs off petrol or electricity, both require roads, parking, fuel / charging infrastructure – and when they are accommodated for on an increasing scale, the city space is still being taken away from people.

Technology is moving in a new and exciting direction when it comes to electric mobility – but should we now decide that self-driving and battery-powered vehicles should run our cities, or instead if there are better ways to make use of urban space?

Clearly, what we should be doing is prioritising people over any modes of transport whatsoever.

Advice From One CityChanger to Another

We summarised some of the key pieces of advice from CityChangers we’ve spoken to that may be useful for cities that are considering going down the road of electric car investment, and some things they may want to consider before doing so:

1. Ask the Fundamental Questions

When asked whether or not we should be redesigning cities with electric cars in mind, former Commissioner of the Chicago Department of Transportation and entrepreneur Gabe Klein responded that “we must always have north stars – but these must always be centred around people and the environment broadly. Therefore, we should not be prioritising modes per se. But when we do, they need to be filtered by whether they are good for societal outcomes.”

He outlined some of the questions that CityChangers should be asking before investing in any kind of electric infrastructure in urban planning:

“We must ask, for example, do the decisions I’m making contribute to health, to positive impacts on the environment, to a more equitable society, to better social cohesion, are they cost-effective on a long-term scale of 30 or more years? Or are we forcing people to make a capital investment in electric transportation?”

2. Do We Really Want to Widen Our Roads?

We know that demand for electric cars is increasing at a rapid rate – and if this continues, eventually we will have to make roads wider and bigger to accommodate the increased number of cars on our roads.

But the problem with this is what’s known as the Downs-Thompson paradox, or induced demand: as roads improve, more people will drive. So even if roads are bigger with greater capacities for cars, they will eventually become just as congested before.

World-renowned city planner and urban designer Ludo Campbell-Reid elaborates that “what tends to happen is that when you widen a road then there’s a benefit for a short period of time. But within 6 months to a year, the traffic is often worse than how it was before you built that extra lane.”

3. Be Cautious

50 years ago, we believed that the combustion engine was the solution to all of our problems. In another 50 years’ time, who knows what position our cities will be in with technology. Perhaps there will be another revolution of a new kind of transport – and then we will have to rebuild our cities all over again.

Therefore, it’s probably a good idea to approach the electric car revolution with caution, as we cannot predict how fast our technology will be revolutionised again in the future.

Ludo noted that “cars are like a gas, they fill every space and every void – and if you allow it, cars will totally consume our public space.”

The Conclusion

Perhaps electric cars will help us to reach some of our goals when it comes to making cities more liveable – especially when it comes to urban air quality. But we should also keep in mind the potential dangers of deciding to fully accommodate them within our urban planning designs.

Who knows what the future of our cities will be like, but there’s never a better time to start putting people first and regaining city space for pedestrians and cyclists to make our way towards better cities for everyone.