Technology and greenery will be more synergetic in cities of the future. Leading the charge for melding nature and the artificial is Professor Carlo Ratti, who is pushing the frontiers of innovation in urban design at a fast pace. He tells us why data is the gateway to integrating nature-based design, why we should be suspicious of smartphones, and how to put citizens at the forefront of innovation.

Carlo Ratti is passionate about cities because they bring people together – to live, to collaborate, as communities. He is also surprisingly modest. When asked why he thinks so many respected design and technology publications have listed him in their ‘most influential’ rankings, he dismisses it as fake news.

He is much more comfortable talking about a lifelong passion for design and integrating the natural and artificial worlds in his designs through increasingly innovative concepts. Indeed, for Carlo, innovation is the driving force. He summarises what this means: “Like Schumpeter was saying, doing old things in a new way or doing new things.”

But what exactly does Carlo mean by the “artificial”?

The Challenge of the Artificial

Known to quote Herbert Simon and his book ‘The Sciences of the Artificial’, Carlo uses the term “artificial” as a shortcut for everything man-made. Although, he adds, the concept is obviously much more nuanced. In this context, architectural structures, depending on the way they are conceived, could lead cities in either a positive or negative direction. For instance, he cites how the twentieth century-built environment was often characterised by cities which architects created as antagonistic and alternative realms to the natural world.

Carlo continues to explain how designers and planners favoured a sprawling city and the issues this presented.

“We often saw buildings or even entire neighborhoods becoming these kinds of spaceships, landing in the middle of the countryside. Cities were expanding and eating up all the nature around and destroying green belts in their expansion. Today, the challenge is the opposite: how can we bring back nature inside the city?”

In other words, the ideal city of the future, to his mind, is one that acquires some features of the natural system, such as the ability to respond dynamically to our needs. Stimulating co-evolution between natural and artificial elements creates more functional, liveable cities. Regardless, reconciling the built environment with the biological, Carlo believes, is among the biggest systemic challenges our urban spaces face.

Seawater as a Natural Insulator

One way to bring nature inside buildings, our CityChangers recommends, is with ‘support’ plants and different growing techniques (hydroponics, aeroponics) as a building block of infrastructure.

He has more envelope-pushing ideas. Such as one project presented at Urban Future 2022, which provides some clarity as to how he combines the disparate artificial and natural sides.

Hot Heart, developed by Carlo’s design office CRA-Carlo Ratti Associati, was a winner in the Helsinki Energy Challenge. As an attempt to decarbonise the city’s energy supply, it is harvested from renewable sources when costs are low and is converted into heat. To store this, it is pumped into water tanks which carry the appearance of “floating islands” in the Baltic Sea, near the Finnish capital’s coastline. When demands increase in wintertime, the heat will be withdrawn and injected into the district heating system – making the concept function like a giant battery, and the basis for a more affordable, resilient heat source.

.

There’s one resource that we now have readily available that helps us optimise a process like this.

Of the multiple dimensions, such as materials and circularity, that make up his ‘utopian’ visions, Carlo tells us one reigns supreme: data.

Big Data: A Creative Component

As an architect and engineer by training, it’s a natural fit for Carlo to be so heavily influenced by data in his discipline.

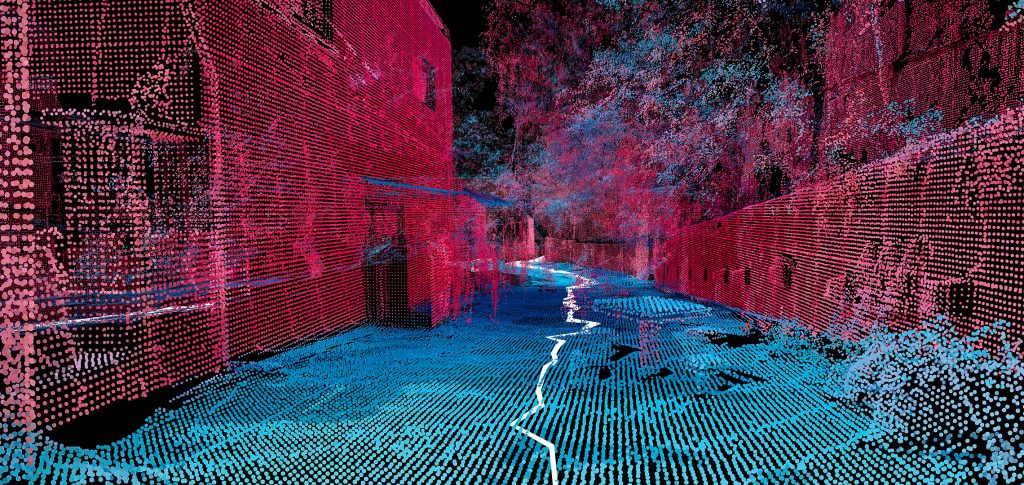

Digital information shines a light on what’s working and what isn’t. It unlocks our comprehension of demographics, resource management, people’s needs and movements, segregation, traffic flows and bottlenecks, and service provision. It aids us in assessing the impact of initiatives and innovations.

These are insights we can exploit today that weren’t available years ago and that lead to solutions that tackle urbanity’s gravest problems – using sensors attached to taxis to assess air pollution levels and road quality, for example. “Data means better knowledge of the city,” Carlo explains.

It’s not a new idea. He notes how Ildefons Cerdà, “the father of modern Barcelona”, already dreamed of how the study of cities could one day become a science in his 19th century book, ‘General Theory of Urbanisation’. Data, Cerdà predicted, would make this possible.

This has become a reality, Carlo recognises, because of the internet, “the most amazing invention of the past century”.

Sensible About Sensors

These days, sensors collect real-time information processed by artificial intelligence. This data feeds into Carlo’s designs. Even so, he reserves an air of hesitancy about it.

He’s wary of the endless streams of data the smartphones we carry collect about our physical movements and digital footprint.

“The accelerometer can be used to see if I’m walking, cycling, taking the bus, taking the car. All this information is collected. It’s shared. We don’t know exactly where. So, there’s some people who know a lot about us; we know very little about them. It is an asymmetry that really bothers me.”

How we deal with data is a discussion Carlo’s team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) contribute to with a series of conferences called Engaging Data. They bring together privacy advocates, big tech companies, and academics to debate information management. Better understanding and use of data will, according to Carlo, benefit policymakers and citizens by making them an integral part of the urban feedback loop. It gives them a voice.

Designers, our CityChanger believes, lie on the intersection between digital data and people power: “I like to think about designers as mutagens.” That is, catalysts for change. It gives citizens a chance to decide what future they want for their city. “Let them be more involved and listened to in the process of proposing new urban transformation.”

And that’s important because the decisions we make now will be felt for generations.

“The society we’re going to build tomorrow depends on the choices we make today.”

The Might of 10,000

Carlo doesn’t work alone. In fact, he mobilises a network of around 10,000 innovators via three operations:

- As professor with the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning.

- Directing the research institute Senseable City Lab.

- At CRA-Carlo Ratti Associati, his international design and innovation practice in Turin and New York, which turns research into on-the-ground projects.

Given how these are such fertile arenas for creativity, they frequently give rise to a fourth channel: start-ups that test new ideas.

These melting pots of professions breed collaboration.

“The important thing really, is about how that is bringing together different disciplines and different skills. People can move from design, architecture, planning; people coming from big data, analytics, complex science, physics, mathematics; it’s also people coming from the social sciences: economics or sociology. You really want to look at all those vectors, because only by bringing that knowledge together, we can make sense of the complexity of today’s cities.”

However, he has found that disciplines can attribute different meanings to a term. It’s important to eliminate confusion and potential conflict by aligning definitions to accelerate progress.

“The first thing is to establish a common language.”

Know Your Audience

The second objective is to share findings. This generates influence.

Carlo speaks of the range of metrics that various disciplines are familiar with. The best leverage for giving their work exposure is to tap into each of them.

Some professionals are used to, for example, publishing their discoveries in Nature or similar top-tier journals. Others aspire to exhibit their work in museums, such as the Museum of Modern Art. A transdisciplinary approach means visions can be shared broadly and discussed in new environs. The consequent feedback informs further ideas and testing.

“Urban innovation is about trying different things. Some will fail, some will succeed. It’s a bit like a Darwinian process.”

The Selection Process

This requires a certain type of person, our CityChanger suggests. He’s developed a “collaborative admissions process” to find suitable candidates.

Carlo builds a selection committee for each project. Stakeholders are interviewed to determine where their perspectives match and who has the “willingness to branch out to other disciplines”.

People at the top of their game do not always get selected because their objective doesn’t align with that of others: “They’re not a good fit, because they want to become number one in the world in their field. What we want is people who are able to branch out.” Teamwork is the name of the game.

Combine the Artificial with Nature Through Design in a Nutshell

Designers can be mutagens, transforming cities, testing, seeing what works and what doesn’t, and constantly improving. Coexisting with natural elements in cities opens up a new world of possibilities. Idealistic urban spaces, Carlo Ratti advocates, are possible if we allow citizens the chance to be heard. Data – the artificial – provides an opportunity for this to occur. It’s an intelligent tool for understanding needs and solutions unlike any we have envisaged before. If we speak the same language, and share a vision, there may be no limit to what cities can achieve.

If you are interested in following Carlo’s MIT courses online, head over to the institution’s Open Courseware page.

We thank Vincent Leung and Daniele Belleri from CRA-Carlo Ratti Associati for their contributions.