A few weeks back, during an ECIU Challenge in Barcelona, I talked with the Office for Urban Ecology of Barcelona’s municipality.

They showed me the city’s plan to win its war on cars.

The plan is to install 503 Superblocks all over the city by 2030. Not only that, they also want to turn all major avenues into walking areas.

It’s bold. It’s ambitious. And it’s happening. Barcelona has a long history of innovative urban practices. Now its plan stretches far out into the future.

Recipe for a Superblock

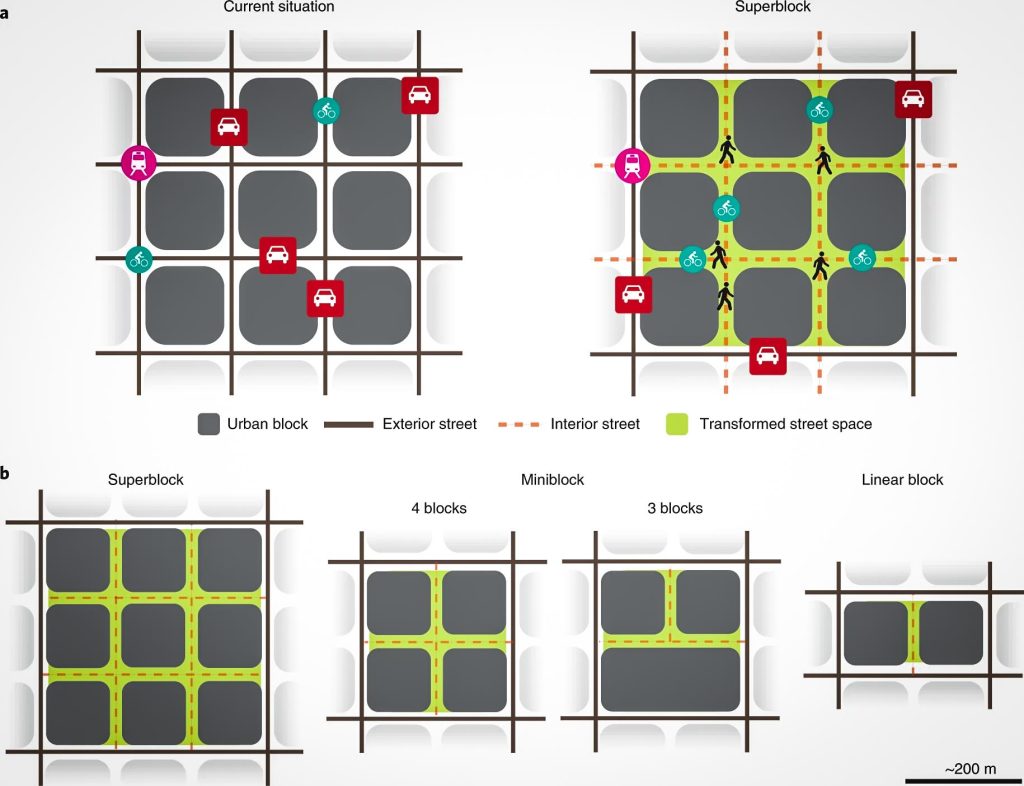

Take 9 blocks on a 3×3 grid. Close all the inner streets off to cars. Divert all traffic to the outer streets. That’s a superblock.

What happens is that all inner streets become “pacified”. You create an island of walking space, green, and quietness without claiming extra land.

When architect Salvador Rueda first proposed the concept of superblocks in 1987, he called them “super-manzanas”. Manzana means apple in spanish. It referenced the shape of Barcelona’s blocks. They are not quite squares, like most blocks in grid-laid cities such as New York or San Francisco. Barcelona’s blocks look more like octagons; the edges are smoothed. This creates more space between them, and increases road safety.

When you take 9 manzanas and force the traffic out on the perimeter, you get a supermanzana.

Today, superblocks have become a buzz word for urbanists all over the planet. The United Nations recently recognised them as an effective climate solution.

They were born in Barcelona for a very specific reason.

Blocks Before Superblocks

In the second half of the 19th century, Barcelona’s city centre was overcrowded.

The municipality asked several architects to plan the construction of a new district to accommodate Barcelona’s demographic growth. Among them was Ildefons Cerdà, an unknown architect and engineer who would revolutionise urban planning forever.

High death rates, as well as the inadequate air circulation and health conditions in the mediaeval city centre encouraged Cerdà to re-think the way we plan cities. Cerdà studied the volume of fresh air needed for every resident, calculated the orientation of the streets so as to give the buildings as much sunlight as possible, and prioritised space between buildings to increase safety.

In doing so, he coined the term “urbanisation,” which did not exist at the time, and formalised it in his General Theory of Urbanisation in 1867.

The result was the Eixample district (“expansion” in Catalan).

As with every revolutionary idea, there was friction. Cerda’s plan was rejected many times before finally being approved in 1860. Today, Cerda’s blocks (or manzanas) are the key feature of Barcelona’s unique city centre, and the Eixample has become an example for the many grid layouts that we see in cities all over the world.

The Downside of Development

What Cerda couldn’t predict was the enormous amount of cars that would take over the streets. Barcelona’s population has increased three-fold in the last century (to 1.7 million in 2023).

But all cities grow, so what’s the problem?

The Mediterranean Sea sits on one side, the Collserola Hills on the other. Barcelona is enclosed. There’s no space for growing. These topographical constraints have led Barcelona to become one of the most densely populated cities in Europe, with 16,000 people per square km. This is 5 times higher than Amsterdam, and 4 times that of Berlin.

As a result, until the 1990s, Barceloners lived in one of the noisiest, most polluted, and trafficked metropolises in Europe.

High population density has many downsides, especially when coupled with a lack of green spaces. Cerda’s plan did not include space for parks, but planned to have green courtyards inside every block. However, 90% of the courtyards in the city centre got taken up by stores.

According to WHO standards, there should be at least 10m2 of green spaces per person. Barcelona as a whole has 6.6m2. The neighbourhood of the Eixample stops at 2m2, including non-proximity green spaces.

Benefits of Superblocks

How do you reduce traffic and create more green spaces in a city that doesn’t have space?

Superblocks! Barcelona’s grid layout perfectly lends itself to Rueda’s plan.

The first experiments were run in the district of Gracia through tactical urbanism.

Tactical urbanism is the practice of installing temporary, cheaper infrastructure in order to experiment with urban transformations. Typical examples of tactical urbanism are the temporary pop-up bike lanes installed in the deserted streets of our cities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

After the experiments in Gracia, the first real superblock was installed in Poblenou. As of now, only a handful of superblocks are built across the city, but the plan is to introduce 503 of them.

In 2017, a superblock was implemented in the neighbourhood of Sant Antoni. Did anything change? What were the benefits? What does the data say?

Before-and-after quality of life measures in Sant Antoni show the effect that the superblock had just 2 years after implementation:

- Air Quality – Sant Antoni saw levels of NO2 reduce by 33% just one year after the implementation of the superblock.

- Quietness – 55% of the population lives in an environment where the average daylight noise level is above 70 db, with the recommended WHO safety level at 65 db. Noise pollution has been linked with several risks such as detrimental mental health and hearing loss. Noisy streets are not used as much by pedestrians. One year after the superblock was completed, noise had reduced by 4 db.

- Traffic reduction – significant decreases in vehicle usage (-92%) was met with no substantial increase in traffic in neighbourhing streets (+3%). The technical term is that the cars “evaporated”: people chose not to use them as often.

Superblocks Beyond Superblocks: Superilla Barcelona

The superblock is now not merely a space. It has become an approach. Adopting the superblock approach means putting people at the centre, literally.

The good news is that you can do that even without resorting to superblocks.

Take the example of Avinguda Meridiana. The Meridiana is one of the three major avenues connecting Barcelona’s city centre to the outskirts. It’s a massive (and noisy and unsafe) six-lane urban highway.

If you can’t have a superblock here, at least you can apply its principles. This is how Superilla Barcelona (the office leading Barcelona’s urban revolution) envisions the future of the Meridiana.

It consists of a small “rambla” (a walkable path) in the centre with two car lanes on each side, bicycle lanes, and very wide street-level sidewalks. The street suddenly becomes liveable, with all the same benefits of noise reduction, improved air quality, and safety. It’s a superblock, just in another form.

Parks, Not Car Parks

The same approach has been applied to the planning of the new Glories Park. Glories, once one of the busiest and most dangerous intersections in Barcelona, will become the city’s second largest park. The cars, this time, will go underground.

Since the project will take so long (10 years), it will be built in phases. For now, a smaller park is already in place there, which will be part of the bigger green area once construction is completed.

The developments of Avinguda Meridiana and Glories Park show that the concept of superblocks is not limited to a grid-layout city. It can be applied anywhere.

At its core, it’s all about putting people at the centre of the street. It’s about turning car lanes into usable, truly public spaces.

Bonus! See for yourself: Barcelona’s office for Urban Ecology is going the extra mile to offer transparency on all current and future projects. You can check out an extensive gallery of superblocks and other interventions at on their website.

This article was written for CityChangers.com by Michele Castrezzati, a sociology student at the University of Trento entering a master’s in Urban Studies. In November 2022, Michele took part in the ECIU “Big data and climate change in Barcelona” challenge where he had the chance to visit Barcelona’s superblocks and learn how this concept has changed urbanism for the better and the multiple benefits they offer our cites and the people that inhabit them.

[1] Eggimann, S. The potential of implementing superblocks for multifunctional street use in cities. Nat Sustain 5, 406–414 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00855-2