Economic hardship drives many struggling city centres to relent and force manufacturing and commerce to give way to residential developments. But some cities are resisting. The historic Abattoir site in Brussels is proof of how we can revive historic districts with modern concepts like circularity, diversification, and public participation.

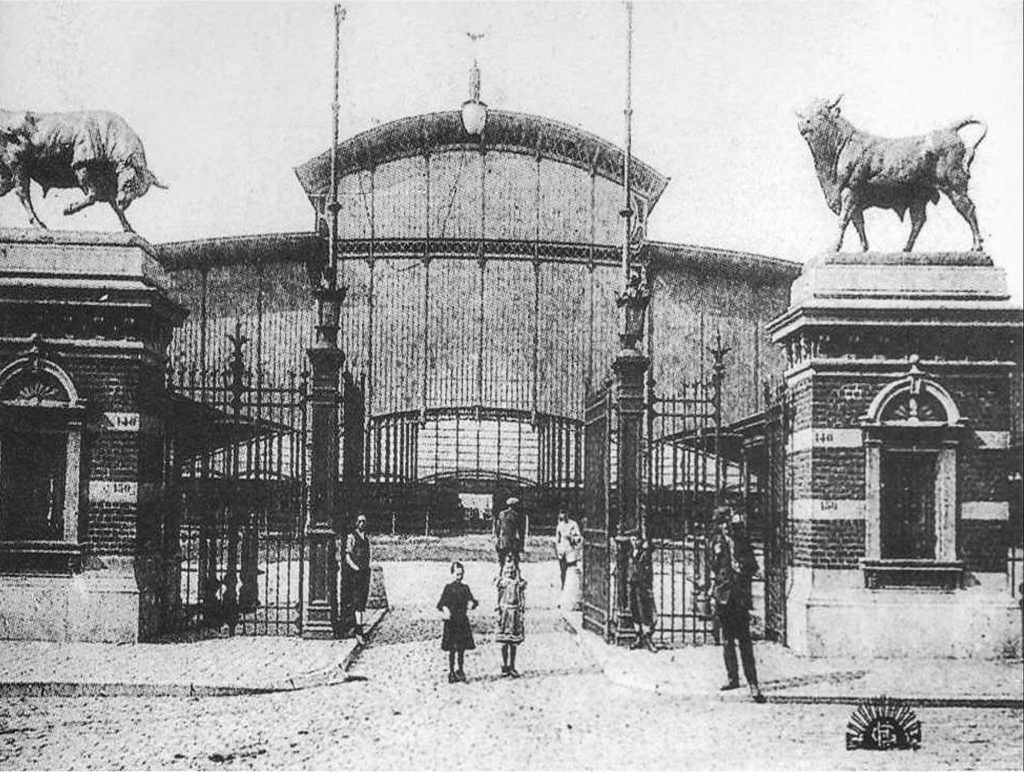

Found in Anderlecht, one of Brussels’ poorest districts, the Abattoir site dates back to the 1880s. This was once a hive of food production, but, by the 1980s, it was too expensive to modernise and was facing bankruptcy.

Financial pressures on similar sites throughout Europe commonly see them sold for lucrative housing deals, pushing SMEs out of their workspaces. Rents rise in what becomes the hippest district in town, forcing the poorest households to move away, referred to as gentrification.

It doesn’t have to be this way. In Brussels, the people behind the Abattoir site dug in. Using a long-term vision, they rallied collective power and turned around the fortunes of a district in its death throes.

Collaborative Resistance

Before the site could be lost to a private developer, 150+ local businesses and investors clubbed together to buy the 11-hectare site. This was 1984 and this action saved the surrounding meat-cutting and food production companies that depended on it. The company Abattoir SA/NV, was formed, and it has managed the site ever since.

Shortly after the millennium, another threat arose. The Abattoir site’s proximity to the Gare Midi international train station led Dutch real estate developers to put in an offer to buy the site and convert it into real estate.

Abattoir SA/NV’s board of directors sensed they could still decide their own future and instead decided to develop their own vision for the site. This was the start of its reincarnation.

The Masterplan: A Master Stroke

Jo Huygh, now a member of the board of directors of Abattoir SA/NV, developed this vision. Together with ORG Architects and a commercial consultant, he proposed a masterplan that would not only preserve the historic architecture but also keep production and commercial activities on the site. This includes a food market, which now see almost 100,000 visitors flocking to the site each week.

Jo explains that, before the masterplan, the company had no long-term vision.

This proposal changed that and saved what is possibly the only remaining inner-city abattoir in a European capital. It gave them guidance and a “red line to follow” to achieve their vision.

The masterplan set out to create a mixed environment, diversifying the activities taking place there.

Going Circular

Inspired by similar sites in Lyon, London, and New York, Abattoir SA/NV created their first big project, Foodmet – a covered market similar to the (albeit much larger) la Villette in Paris – making space for 50 stallholders.

Not forgetting the purpose of the original abattoir, on the ground floor, the Manufakture project was the next project to be developed. This, importantly, preserves the meat producing and cutting industries and makes room for food related start-ups to develop.

The real feather in the cap, though, is how waste is recycled as a resource on the Abattoir site.

On top of the covered market an urban farm has been set up, which utilises the heat of the food market’s refrigerators – a by-product – in its greenhouses to both grow vegetables and heat water for fish production.

Situated on the roof is an aquaponics project. Fish are raised for food, and the water they inhabit and the carbon dioxide they produce are reused in vegetable and herb production. It’s efficient and all natural: no chemicals, no pesticides.

Meanwhile, down in the darkness of the Abattoir site’s basements, mushrooms are grown on wheat leftovers from nearby breweries. And under highly efficient LED lighting, Eclo‘s vertical farms are cultivating baby herbs – packed with nutrition – producing three times as much as conventional growing methods can for the same surface area.

Investment Begets Investment

Three decades ago, there wasn’t much hope for the old abattoir’s future. Now it’s a vibrant community.

The gamble to try something new has paid off. In a world where sustainability is increasingly valued, investors are getting braver about what to chance their money on.

Much of the Abattoir site’s development has been made possible by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), which recognised the potential of the masterplan’s clear vision.

That was enough to leverage support in the form of a bank loan and ERDF subsidies from the Brussels region and Europe. This has funded a huge chunk of the development, Jo notes. Brussels’ regional administration has added a further cash injection by buying a parcel of land on site, next to the canal, with plans to build affordable housing.

Diversifying land use and income streams is known to offer security to a district.

The masterplan also sets out a vision for leisure facilities, such as a rooftop swimming pool on top of the Manufakture, also warmed by residual heat from the activities in the building below.

“One thing that is sure is that there will be a heat network on site.” Our CityChanger refers to the link between the projects on site – such as the Foodmet and Manufakture building – and the new (and existing) housing nearby, such a student housing in the upcoming Kotmet project.

“That has been the idea from the beginning, to link everything, because we think that in terms of energy, this will be the best solution.”

Rewrite the Law to Your Advantage

Jo’s advice for reinvigorating sites like the Abattoir site is to take the plunge and just do something.

Innovation is about trying something, being confronted with obstacles , and eventually, if needed, rethinking it.

This is how Abattoir SA/NV’s positive energy district came into being.

Because the historic covered market building is a listed monument, it was “impossible” to get permission to add photovoltaic (PV) units to the for solar power generation when discussions first started.

But priorities and minds change. Almost a decade later, energy conservation became a hot topic. Now the covered market building is full of PV panels. “So, you see, there is also an evolution of our ideas about sustainability and the future of this world.”

While legislation prevents this electricity from being sold on to consumers, sharing the power among the merchants on site is tolerated. And it would now be difficult for anyone to close it down.

A clause in Belgium’s constitution prevents laws from negatively affecting the environment.

So, lawmakers struggle to impose restrictions on initiatives that are proven to work.

Jo encourages CityChangers elsewhere, who maybe don’t have the law on their side, not to give in, but to shift the focus of change: “Maybe the law is the problem, not your project.”

You’re (Not) Speaking My Language

It’s a wonder the Abattoir site has undergone so much structural and aesthetic renovation at all.

Many countries have protection orders for buildings deemed of cultural value. Getting permits to change the face of heritage architecture can be a real challenge.

But for Jo and his team, the legalities weren’t the holdup.

Belgium has three official languages: Dutch, French, and German. The company’s statutes, and consequently the Foodmet’s building permit documents, are written in Dutch, but – it turned out – the officer assigned to their building permits spoke only French. This threatened to delay proceedings.

This is why, Jo reminds us, it’s important to keep the pressure on.

Obstacles may not be clear. When you don’t get a reason for delays, push for answers.

A Public Meating Place

A benefit of keeping the Abattoir site alive is the continuation of traditional industries, from “beautiful designer woodwork shops” to the meat production itself.

Meat production is a contentious subject in terms of animal welfare and environmentalism, but here it contributes to the economic prosperity of a deprived region of the city.

The Cureghem neighbourhood of the Anderlecht commune (district), where the Abattoir site is located, is populated largely by migrants, “new arrivals”, and low-paid communities.

Given the diverse population, voices in the former Abattoir Quality Chamber – a committee of “experts from the economic sector and the academic sector and the public sector” who reflect on the project – pushed for the representation of international architecture in the Foodmet’s construction.

But getting citizens to contribute their own ideas in the development was hard going.

“If you apply for a building permit for a project like this, public consultation is part of the procedure. We decided to organise public meetings to explain the project,” Jo explains. “We’ve done more meetings than we are legally obliged to. But we saw that it was very complicated to attract people to these kinds of meetings and to involve them in the discussion.”

.

The People’s Abattoir

Eventually the media caught wind of the masterplan and encouraged the community to come forward.

One person suggested making better use of the open space on site, such as the space under the covered market building. Abattoir SA/NV surprised her by handing over the reins.

The Cultureghem association now regularly runs social-cultural events. “They involve a lot of people from the neighbourhood,” Jo beams, and for good reason: public dinners, cinema nights, exhibitions, and dance performances pull in the crowds and bring vibrancy to the Abattoir site.

And how do people feel about the Abattoir site now?

“Many people are proud of it,” Jo exclaims. Considering the masterplan is still in its early stages, the future bodes extremely well for this district, which has impressively kept dereliction at bay.