How does so much historic architecture endure the ravages of time? It’s because the architects of yore knew how to build cities to suit their environment, and they did so to meet the needs of the people. Omar Zahran, a Young Leader from the 2023 cohort, explains what lessons architects can learn from the past as they build cities of the future.

As the people who design buildings, architects have a direct influence on the makeup of a city and, in turn, how the urban environment affects our lives.

They can create liveable places by including that which people need, for example, green walls, organic shapes, natural materials, and shared public spaces in their plans.

To us today, the cities of antiquity that grew organically may appear to be chaotic because they differ from the much-planned places we’re used to seeing from modern times.

In cities like Cairo in Egypt the two exist side-by-side, but the buildings from the twentieth century arguably fail to meet the same human-centric standards as their historic counterparts, Young Leader Omar Zahran tells us. This, he feels, needs to change.

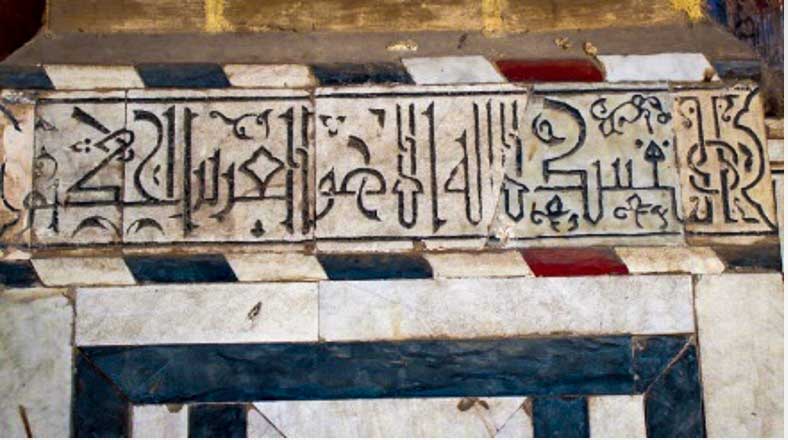

The Artistry of Architecture

Growing up in Cairo, Omar was exposed to many distinctive artistic and architectural influences that date back from Pharaonic times thousands of years ago. These layers of civilisation overlap in the very fabric of the city.

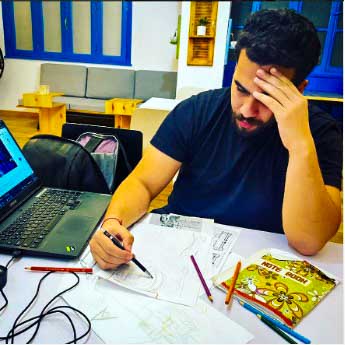

Omar’s appreciation for all artforms, and especially his enjoyment for painting, inspired him to become an architect and urban designer.

“I believe that all arts, like cinema, architecture, music, and painting and so on, are connected somehow. And the mother of all these arts is architecture.”

He believes that a building is an artform in itself: architecture has the power to affect the way people feel – in much the same way urbanists promote elements of liveable cities that not only provide a function but improve our relationship with the built environment.

Architecture is the art of building, not just constructing.

Architecture as art, however, seemed to disappear as rebuilding after the second world war coincided with booming urban populations.

Build Like an Egyptian

To outsiders, the thought of Egypt may evoke iconic images of pyramids and towering statues depicting ancient gods, but these ceremonial monoliths are an exception.

Like hundreds of other cities, over the course of the twentieth century, Cairo put the grandeur of the past aside and opted instead for quick fixes. New towns featuring featureless giants of buildings – housing blocks and factories – were hastily erected to meet demands for residential and industrial development. The social and environmental problems associated with this surge in people and buildings has a knock-on effect on the heritage too: pollution and traffic damaging old treasures.

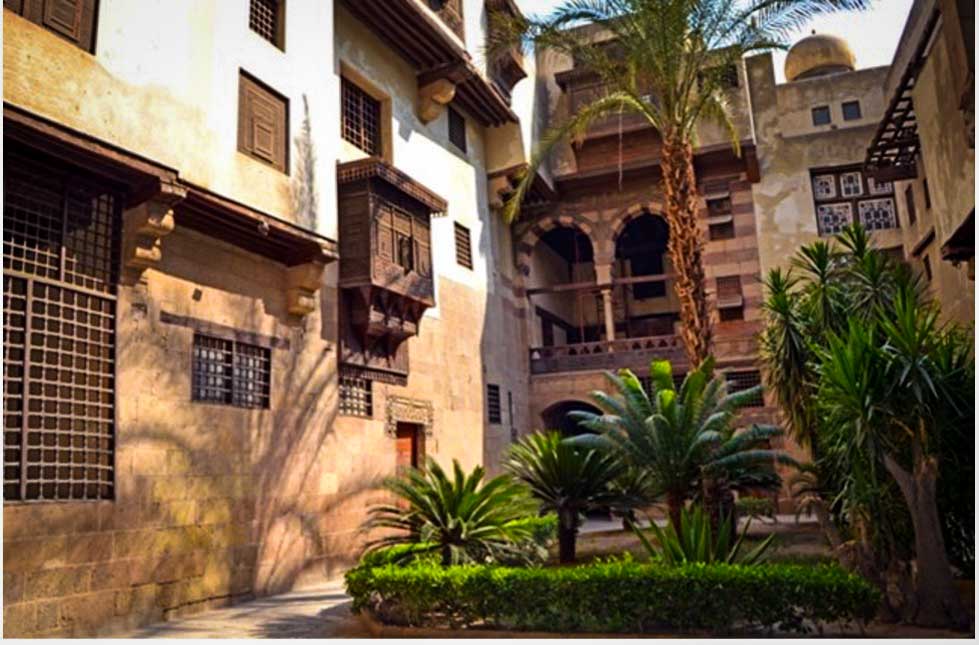

Omar reminds us, though, that there is a different side to the country’s construction, one that’s much easier on people and places: the bustling everyday streets clustered with markets, city walls, and houses – some dating back hundreds of years.

Most of these were built long ago, but they still serve the purpose for which they were intended – meeting citizens’ needs.

Although he’s only been practicing for two years, this Young Leader has worked with prominent firms such as Mimar and EIIDT. His designs are characterised by human-centric practices influenced by the long line of multicultural builders from his country’s rich heritage.

Our main goal is making projects human-centred, sustainable, and resilient. Real sustainability is not just about putting up some solar panels. Sustainability means design for a better planet, a better life.

The Cutting Edge of Cairo’s Architects

Omar recognises that many places in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, like the historic districts of Cairo, are defined by the human-centric principles of Islamic culture.

This is, Omar calls it, “the most sustainable architecture in the MENA region”. That’s because it developed to meet the needs of the inhabitants.

One way is by protecting people from the elements.

Building housing with thick walls made of natural materials, for example, which maintain a steady temperature in the hot climate. Another was to build close together, and grading-in public spaces, which protects inhabitants from noise infringes. The inner courtyards of traditional Cairene houses provide better light and ventilation.

“A house is not just a house; it’s not just four walls covering you,” Omar explains. It is almost an organic extension and expression of the family that lives there.

That’s why plans should be informed by the needs of the community and should never be assumed.

These needs can differ between neighbourhoods, entire cities, and certainly from continent to continent.

You can’t make the same house for people who live in Aswan as you would in Europe. It’s a different climate – they would boil like eggs!

MENA’s Architectural Legacy

Human-centric design is prominent throughout the Arab world.

Abdullah S. Yawer et al. cite the historic city centres in the MENA region as “great cultural assets” with “attractive streets and public spaces” that are districts of social and commercial activity. And yet, they are under threat of destruction “as a result of urbanization, growing pollution, and limited resources”.

After surviving for so long, it’s now left to CityChangers like Omar to protect them.

“We must ask ourselves, how are these buildings still standing? Because they’re sustainable. Because if people didn’t like them, they would have been demolished. We must learn from it; we must conserve it and reuse it [or apply] adaptive strategies.”

Omar inherited this philosophy from his manager and mentor, the iconic Egyptian architect and planner Professor Adel Ismael, who was himself trained by Hassan Fathy, a pioneer who conceived the concept that sustainability in architecture should be a domain of the poor, not just the wealthy.

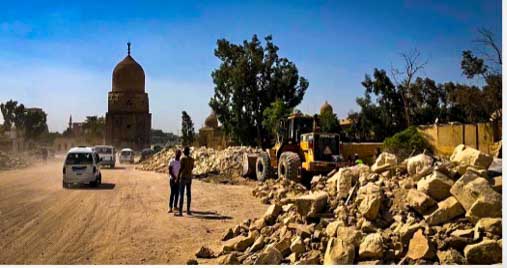

A Living Museum for Funerary Art & Architecture

One of Omar’s projects is to document and come up with proposals for redesigning Cairo’s City of the Dead. More correctly called Qarafa, this is a sprawling area of graves and mausoleums in the heart of the city.

As Cairo’s population boomed – it now stands at 22 million – the demand for real estate pushed up rents. People on low incomes are being forced to find alternative accommodation.

Qarafa has become one of the informal settlements they’ve turned to, residing side-by-side with those that have passed. Estimates put the population at 500,000.

Some may think this morbid, but Omar sees the beauty of Qarafa.

“It’s magical! It’s a really, really great place. There’s a lot of architectural styles, a lot of historical people buried there who affected Islamic history and Egyptian history… and global history.”

He considers the murals of grave art to be “treasures” worth preserving, as does UNESCO.

But this unique urban fabric is not protected. “They are demolishing tombs, and the government does not care about it. They see no opportunities in it,” Omar says regretfully.

Image credit: Omar Zahran

Image credit: Omar Zahran

Image credit: Omar Zahran

Officials are clearing it to build roads, bridges, and other infrastructure to serve the city.

This, Omar believes, is one of Cairo’s greatest architectural challenges.

However, protecting the heritage is not beyond question.

Many artists work there too, such as engravers, Arabic calligraphy artists, and more. Omar has proposed turning the site into a living museum, both to protect the historic architecture but also to recognise the human activities that occur there.

.

If it goes ahead, “[i]t will be a great change and it will have a great economic impact for people,” Omar estimates. “It’s the thing I’m most proud of.”

And why shouldn’t he be? Like those who have built before him, Omar is set to leave a lasting and positive legacy on the fabric of Cairo’s streets and the quality of the lives of those who inhabit them.

With his vision and aspirations, it seems that the region will find its way back to constructing in a people-centred manner, which could potentially lead the world not necessarily on innovation as much as rediscovering what we once knew to be the best way to build. Maybe because of Omar, we will one day forget that ever changed.