Does history affect our relationship with cities? According to Young Leader Aleksandr Vlasov, the Soviet era has left a modernist mark on social attitudes and the physical makeup of Russia’s urban spaces. Thankfully, up-and-coming designers and planners like him are taking on the challenge and championing transitions that create more comfortable (former Soviet) cities.

“In Russia, we don’t have a long history of quality urban space planning and development since the 1960s.” So explains Aleksandr Vlasov, a designer and city planner who studied a master’s degree in Urban Design & Territorial Branding at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics. In some way, that explains why the field was unknown to this Young Leader until he encountered bloggers writing about urbanism in 2015, little more than five years since it became a mainstream topic for discussion in the country.

Prior to this, Aleksandr took an Advertising and Public Relations degree at the Moscow Polytech University (MPU). Even then, he felt this wasn’t his destined path. Exposure to sustainable design changed something in him: “I started to be concerned about the environment outside of my apartment.”

A Change of Perspective

Aleksandr wants to make places more comfortable. It’s a word we don’t often hear from city planners, but it makes so much sense! Liveable, enjoyable, easily navigable, temperate cities where it’s easy to access the goods and services we need – “comfortable” sums it up nicely.

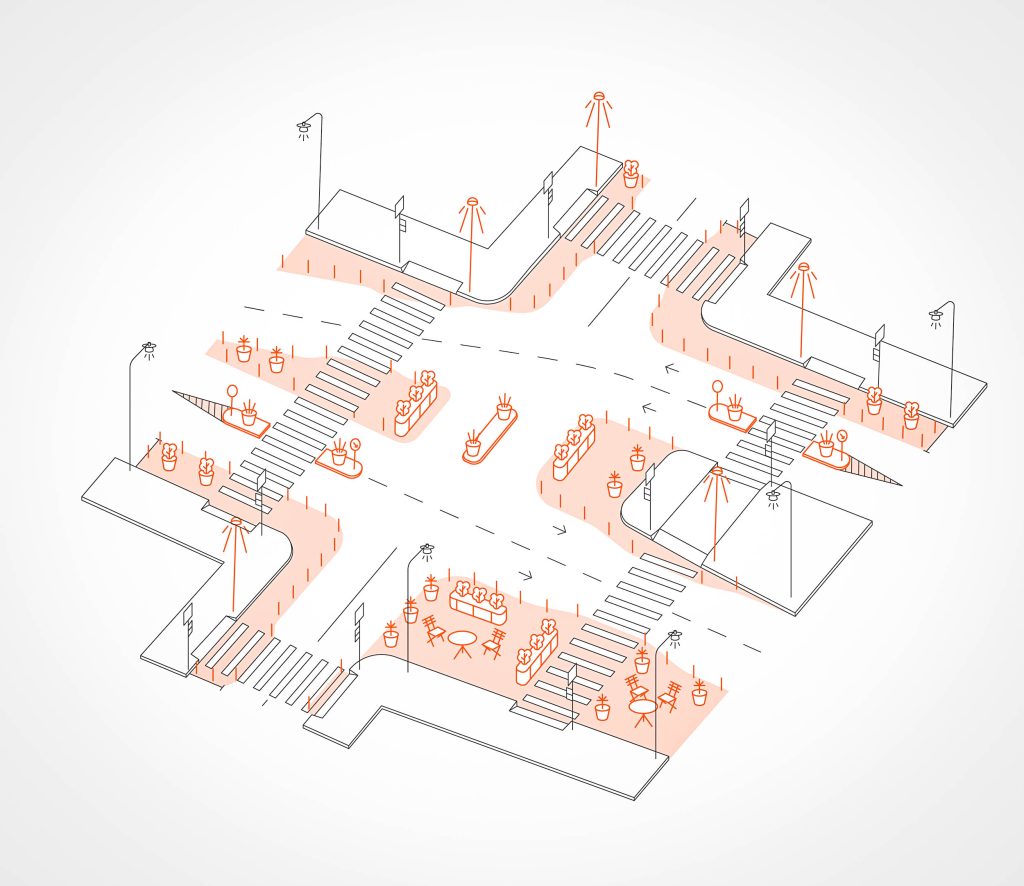

“In my opinion, a comfortable city is about proper design, furniture, lighting, greenery, and so on. It’s about making places where people feel like they’re at home. And home expands to the city scale.”

In this CityChanger’s opinion, the Russian urban environment is often “abandoned and bad”. Due to “the lack of a strong civil society,” as Aleksandr puts it, “people think that they don’t influence anything”. This pushes many citizens to stay indoors much of the time. In their apartments where they can make decisions and changes. Therefore, “an apartment is more important for them” and city structures get little attention.

Towards the end of his bachelor’s degree, Aleksandr decided he wanted to make a difference. “I really understood that I would like to make the environment better and educate people that it’s really good when you have a comfortable, functional, liveable city.” That’s why he started volunteering.

Vision Zero

Like many cities, Moscow is a hive of motorised vehicles. In 2012, City Projects – or “Foundation for Urban Development ‘City Projects of Ilya Varlamov and Maxim Katz’” – was established to bring together authorities and citizens to beautify what was an area unfit for walking.

When Triumfalnaya Square near to Mayakovskaya Metro station was due for redevelopment, urban blogger Varlamov and Katz, a famous opposition politician, organised a protest to push for an open professional architecture competition. They got their way. “Before this,” Aleksandr explains, “the Moscow Complex of Urban Planning Policy and Construction developed projects as closed tenders without involving quality architectural firms and the participation of residents. It definitely resulted in bad-quality and outdated planning and design, or the absence of it”.

By installing swings and benches and good lighting, they showed Muscovites that “it’s better to have some furniture, some green spaces, then to have a car in such a crucially important urban space like a town square”.

The now common presence of architectural competitions and consultation with residents has created a shift towards quality space developments. After a few years, the experience began to spread throughout the whole country.

City Projects took off. It went on to create initiatives, give lectures, translate and distribute printed and digital materials, and now also works with volunteers and share their knowledge on social media. They released a book – “100 Tips for Mayors” – to promote up-to-date European and worldwide approaches towards urban design and planning throughout Russian municipal authorities.

This was influential for Aleksandr. Skip forward almost a decade, to when he joined the NGO on their Vision Zero project; a movement aiming to make city mobility safer. It’s an important focus: our Young Leader, who is now a head of the Tagansky District branch of City Projects in Moscow, explains that “we have problems with speed restrictions in Russia, because there are quite low fines for speeding”. The incentive for prevention just isn’t there. Although better than a decade ago, “outdated approaches to street design” make this worse still. We’re talking about wide streets, high speed limits, and priority given to cars over pedestrians and micro-mobility.

Making full use of his skills and experience in graphic design, Aleksandr put together a book that throws light on the problems and frequency of traffic accidents in the city. It uses examples of tactical urbanism from Europe and car-centric USA, and visualisations for solutions specifically for the streets in Moscow’s Sokol district. It was shared widely with the district authorities and on the web.

Sign of the Times

As you may expect, as a designer-cum-urbanist, the heritage of urban fabric is important to Alex. Preserving it is a concern for many Russians, who donate to the NGO, Vnimanie Foundation in support of their mission to save Russian architectural heritage. “I really adore it,” Aleksandr exclaims cheerfully, explaining how the organisation trains volunteers throughout Russia in the art of restoration.

“For about five months, we restored the interiors of buildings in the historical district of Moscow. And it was a really good experience in the way of networking and connecting with people.” And for gaining hands-on skills in restoration, he adds.

It wasn’t the first time this Young Leader worked on a heritage project. In his hometown of Alexandrov, he restored the font of the city’s Soviet-era signs dating back to the 1960s-70s. In doing so, he creates a positive aesthetic that solidifies a citizens’ relationship with their environment.

Wayfinding

Aleksandr is a tireless CityChanger and proud of his work. From commencing university to today, he has developed concepts for the waterfront project in Fryazino, the reconstruction of the historical centre of Klin, and two transit maps: Alexandrov and Dubna.

Aleksandr also gave a lecture during an event at the Moscow branch of the Goethe Institute, where he spoke about eco-friendly urban planning.

This has all led our Young Leader to a realisation: “Urban design and planning is definitely more than appearance; it’s also about functionality, about how cities work, what amenities are used by residents, and also about deep things, emotions, and feelings”.

Maybe that’s why, among the various landscape and architectural projects he worked on at university, one was an accessible and multipurpose city toilet.

While this might seem obvious to the Young Leader now, an holistic approach of combined aesthetic and function – and incorporating liveability – has long been missing in Russia. Thanks to Aleksandr work, that’s no longer the case.

Winds of Change

Compared to other European nations, Aleksandr gauges progress in the authorities’ and developers’ attitudes towards sustainable cities as slow. They frequently build as western countries did in the 1970s and 1980s: the modernistic model of, as he puts it, “an inhuman scale of buildings, a lack of liveable spaces and street retail, a car-oriented environment, and a lack in the necessary amenities and infrastructure”.

“It’s not about whether people want or don’t want to use a car. In some districts they literally can’t live without a car!”

While the pace of progress is frustrating, he sees it changing. “People are starting to be concerned about what they have outside their apartments”. Various urban bloggers and non-governmental organisations, he believes, have been “really helpful to get to this point”.

Have Hope – Overcoming the Challenges

A bigger challenge for Aleksandr was the personal change from advertising professional to the urban realm; he lacked the skills in planning and spatial design enjoyed by his classmates.

“Urban design and planning are perceived as really hard spheres and you’re really responsible.”

As a planner your name is forever linked to the development that is implemented. This wasn’t something he could wing! Under the pressure, Aleksandr may have come close to giving in during the first year.

Persistence paid off. He began to navigate the maze of information, source the right books, acquire the relevant know-how. Aleksandr started to see how this field is totally interdisciplinary: a background in design worked in his favour.

This CityChanger discovered he had the skills to “understand what you can do for people living in a city: some infrastructure, knowledge about how you can form the environment where people can live comfortably. A liveable city, a walkable city”. And he had the visual knowledge to present his ideas, to communicate concepts to authorities and citizens. As Aleksandr says himself, “I think you have to implement some really good slides, some really good designs to impress them.”

Aleksandr’s conclusion and advice are one and the same: “Don’t lose hope.”

Even in seemingly unchangeable conversative environments, transition can occur.

“I am sure that the young Russian generation looks different at what cities should be. We are definitely more European oriented than others. It is also important to educate people and, perhaps, they could take part in making changes in the future.”

Soviet Cities, Hope & Heritage in a Nutshell

Regardless of where we are, or the political, urban, or historic landscape, we can create change. Soviet cities, like other modernistic places, are slowly becoming more liveable and sustainable. By making urban centres comfortable – while respecting the social and built heritage – Aleksandr Vlasov is tempting Russians out of their apartments and creating a sense of pride and interest among citizens for enjoyable, liveable cities. Above all, he gives us all hope for the future.