Since writing his thesis on “Recyclable Building in Residential Construction” over 20 years ago, Thomas Romm has only delved deeper into how we can reduce the environmental impact of construction and planning practices. Cue: Urban mining. We sat down with Thomas to talk all things urban mining, circular construction, deconstruction, and creating new business models.

It’s fair to say that our supply of resources is not exactly getting any larger. Meanwhile the demand for said materials continues to grow exponentially. And it doesn’t seem there’s a secret stash somewhere for us to dig into when we get desperate. Yet, we still need buildings to live, work, relax and enjoy ourselves in. Never fear CityChangers, Thomas and his team at forschen planen bauen may just have the answer to our resource issues with their three-pronged approach in research, planning, construction.

Diggin’ It: What Is Urban Mining?

If you break this down, the term basically does exactly what it says on the tin:

- Urban – cities, built environments, buildings.

- Mining – to obtain, extract, or dig for materials.

Urban mining is “the process of reclaiming raw materials from spent products, buildings and waste”.

In this case we’re ‘digging’ through the urban environment or a construction site to obtain or extract all reusable or recyclable materials and resources. Therefore, these valuable resources remain ‘active’ for longer. In reality, we’re not really digging up anything new. As Thomas’ architecture office forschen planen bauen suggests, it’s more about “the intelligent use of resources, the recyclability of constructions”. The demand for mineral building materials globally has tripled over the last 20 years, meaning recycling and reusing are crucial if we are to meet the ever-increasing demand for resources.

Re-using and recycling materials from construction sites can take multiple shapes and sizes. Here are just a few examples:

1. Excavated Earth

This is usually dug up and removed from the building site, yet a lot of this material actually has potential. For instance, in Germany, it is thought that ¾ of excavated earth can be utilised rather than sent to landfill. The quality of the soil and the levels of impurities and pollutants will influence how it can be used.

2. Topsoil

If soil is dug up but cannot be used in construction, there is still no need to throw it away. Fertile soil is a nonrenewable resource. In fact, nature needs 500 years to produce just 2cm. Such precious material can be used in planning the form of balancing earthworks, for green roofs, for backfilling and terrain modelling. Additionally, lightweight, and water-absorbent aggregates, such as crushed brick from demolitions, can be used to improve and optimise soil properties to serve climate change adaption – the sponge city.

3. Sandy Gravel Excavation

Also found in excavated earth, it could be “turned into aggregates for concrete on-site without much effort”.

4. Demolition & Construction Waste (DCW)

The onsite use of DCW is an important planning issue. The processing in mobile machineries onsite reduces emissions by 90 %, Thomas tells us. The use of DCW as drainage material, recycling sand and road foundations diminishes the need for primary resources as well as lowering building costs.

5. Individual Elements Which Are Kept Intact

If the original building is being dismantled, the individual elements are reused in the new building or put to use elsewhere.

6. Reusing the Structure

If a building is to be demolished, rather than tearing down the whole thing, the structure is left standing, is strengthened, and reused. Like Botox for humans, essentially, the old structure is just given a face lift!

Building Up and Building Down: Deconstruction

As with most things, eventually there comes a point when a building has seen better days. Let’s talk about the end-of-life phase. Perhaps a building is run-down, out of fashion, or has even been left abandoned; or maybe it’s actually in pretty good nick, but people no longer want to use it.

“Why must we demolish the whole thing, see it come crashing down and act like we’ve got to build a completely new building?”

This is where reusing and recycling stretch even further. Rather than tearing down a building, why not consider deconstruction. i.e., dismantling the building, taking the different components apart and reusing or recycling each of them.

“Deconstruction has only really been recognised in the last ten years”, Thomas tells us. It is not only important to note this as a method for dealing with the building site itself, but also something to bear in mind when planning and constructing a new building. Thomas highlights that we’ve got to ask ourselves: “How can I construct a building today which I can easily deconstruct later?”.

Plus Points

The term ‘recycling’ should only really conjure up positive images as an incredibly advantageous process however it is implemented. And recycling in terms of urban mining is no different, with multiple benefits for everyone involved.

- Compared to primary raw materials, using secondary raw materials or recycled materials from on the building site itself requires zero transportation. This saves a lot of fuel, emissions, and energy. It has been estimated that “2/3 of inner-city freight transport is to and from building sites”. As well as saving on pollutants and dust particles, by reducing construction site transport, we are also lowering the amount of noise pollution.

- Recycling improves resiliency to climate change. For example, if recycled materials are used on green roofs, they can make the soil’s ability to retain water better, thereby reducing rainwater discharge and acting as a flood protection measure.

- Urban mining helps to “increase the environmental efficiency of construction work”.

- Recycling on site can often save on disassembly costs.

- Such processes also shorten time it takes to complete construction.

- Moreover, the EU Waste Framework Directive states that they do not class excavated soil which is reused on the same site it was extracted from as waste. This means that builders, developers, and contractors don’t have to worry about waste treatment in the same way they would if the soil was to be sent to landfill or reused on a different site. So, re-using and recycling excavated soil saves time and money on waste treatment.

Loop the Loop: Circular Construction

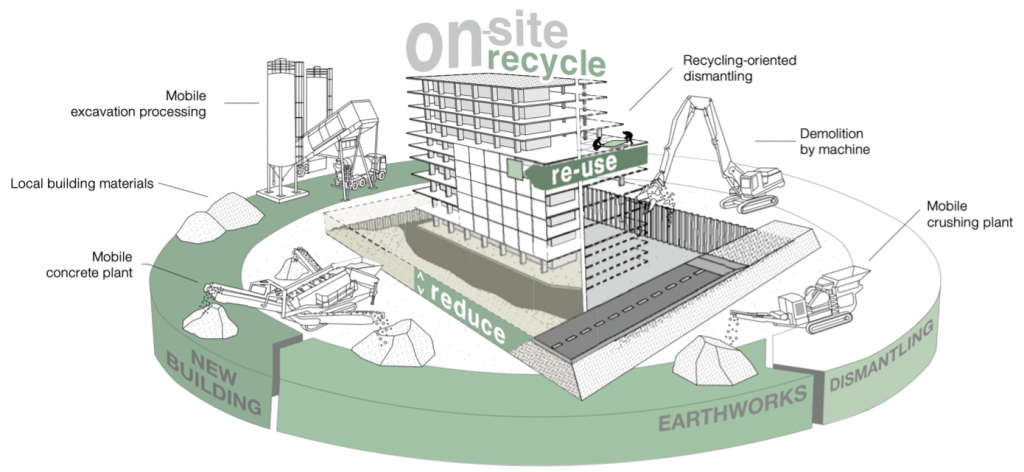

Urban mining could be a significant step in making our construction projects more circular. By circular we mean, much like the term circular economy, a “restorative and regenerative” system in which resources are kept ‘active’ and reused. Here we can apply the 3Rs of dealing with waste: reduce, reuse, recycle. According to the office of forschen planen bauen, this translates to: “on site recycling, re-use of materials, reduction of material flows”.

Sounds simple enough, right? So why aren’t we further along on our urban mining and circular building journey? Thomas suggests that, among other reasons, it’s due to the way construction projects are currently run with multiple building firms involved. “On the one hand, this is good for diversifying from the state”, he says, “but on the other hand, it is inefficient in terms of the construction processes.”

In addition, traditional construction practices are still very much engrained, despite sustainable methods consistently proving to be “cheaper, more affordable, and more cost-effective” Thomas tells us. And they have the added bonus of having a positive impact on the environment.

Thomas continues by explaining that it costs €1,250 per ton to dispose of mineral wool which is several times more than the initial production cost, i.e., throwing materials away can be more expensive than making them. The solution? Don’t throw them away but return them to the producer.

Of course, there are other issues too. As Thomas points out, if money really did rule the world, then the construction industry would have introduced these strategies long ago as they are more cost-effective. But other aspects also influence people’s willingness to change lanes. Of these processes people may think, “it’s too laborious, it’s too slow, it’s already been allocated to someone else”, explains Thomas. He adds: “And there are some very strong business sectors for whom even money isn’t enough of an incentive.” Our expert does, however, display some optimism, as there are people who are interested. The problem is that these are often “the sub-groups who can’t make a lot of difference”. Of course, the more people, the better, but perhaps it’s time to start targeting the bigwigs with the sway to influence others and make a real impact.

The Next Steps

So, what do we still need to do to implement urban mining and make circular construction the norm? Thomas gave us his insights into the four areas which need to be put in the spotlight.

1. Think Again

The first step is taking a good, hard look at ourselves and our practices and “rethink these processes and understand them differently”, Thomas reports, “then we’ll be able to construct every building in a circular way”.

This means reconsidering every ingredient and every step of the construction recipe. It’ll make little difference if we build with highly sustainable, natural materials but use them in non-circular processes. Linking back to deconstruction, Thomas elaborates, “we need to completely rethink how we can build more robust structures which we can continue building and re-building in coming generations, which are tough and flexible enough in the first place to stay standing for a long time before they are dismantled because we don’t have that much material left.” By constructing buildings that last longer or have an adaptable structure so they could be used for various purposes while also making them easily deconstructable, we’d already be saving time, money, and resources.

Thomas tells us that there are certain sectors which already use the same construction methods every time and that the structures are most often industrially prefabricated anyway which makes them easy to disassemble. Yet, they still aren’t built with deconstruction in mind. He insists that “dismantling needs to become the norm, rather than demolishing and recalculating”. Some specific examples of areas to focus on, according to Thomas, include commercial developments, warehouses, and the logistics sector.

2. All Aboard

There are numerous interested parties when a construction or deconstruction takes place. The lack of crossover, communication and involvement of all actors throughout can really hinder the ability to make these processes circular. As an example, Thomas describes how “we always have far too much soil on our hands as soon as we construct, and no-one has any idea what to do with it. But urban planning is not connected yet to construction issues – at the beginning so much can be initiated.” Just by involving a range of people and processes, the solutions for all those extra-earth-problems could be solved.

The belief at forschen planen bauen is that if we can close the gaps between the different, interested parties and ensure that everyone is involved throughout, then a lot of progress could be made in terms of sustainability. Thomas describes their work as aiming “to get this large crossover of people who are concerned with construction involved in such processes because everyone can contribute something”. By “everyone” he refers to: urban planners and developers, landscape architects and architects, the civil engineers, construction companies, excavation and demolition firms, the approving authorities, the waste authorities “and all the way up to the City Planning Director”.

“There’s a whole group of different parties involved who have got to contribute here in order to change construction. That’s the idea.”

3. Rules and Regulations

While there is much to be done in the realm of construction, our expert strongly believes that there are also steps to be made in terms of regulations “which will make a new way of constructing possible”.

Thomas revealed that some of his latest work involves figuring out a way to create a legally binding situation for circular building. There were first questions of what form this should be in: “Should we create a tax? Should we set up a levy like in the waste sector? Or should we write an OIB 7 [Austrian Institution of Construction Engineering] – a guideline that belongs to the building regulations and has to be shown like an energy certificate?”.

And it’s the idea of an OIB 7 which has taken off. The concept is similar to that of having an energy certificate or a structural engineering calculation, both of which are processes and documents which are needed and are now taken for granted. Equally, Thomas argues, “we think that it’s also necessary to document the circularity of a building and for it to be required by law”.

At the start of 2021, forschen planen bauen worked with the Federal Environment Agency in Austria to carry out a stakeholder investigation. Thomas explains that “it should act as the preparation for a white paper, for the draft of a law”. This process is currently ongoing and is being observed closely by Thomas and his team. “I think this will mean we will have achieved an important prerequisite”, he remarks: a vital step towards making circular building a priority.

4. New Business Models

Closely linked to making circular building legally binding, forschen planen bauen also dedicates time to conceptualising new ways of doing so in practice: “We work not just on ideas for how you can measure what is circular and how we can compare lifecycles, but also on the business models behind this”. The aim being that people will then be able to picture the outcome from an economic perspective. This could turn out to be more profitable than the traditional way.

It’s all about redefining the processes, logistics and business plans behind building and making these new strategies the norm, not the exception to the rule. forschen planen bauen develops, researches, and supports these new business models alongside clients and as part of the large construction sites that they are supervising. He explains that most of these are sites where “it’s not about just trying something out, but where a lot of living spaces have got to be developed quickly and for very little money”. There’s a huge amount of expertise here and a lot we can be learning from Thomas, and his team.

The belief is that if different business models can be established, if there is proof that they work, then people will no longer hesitate and question their efficacy and resort back to conventional planning and construction strategies. It’ll be just as easy to turn to these circular building methods and business models as it has been to turn to the current practices up to now.

One business model to make the norm is that of using whatever the available building materials are on site in the construction itself. For instance, to “create new models where it is clear that you don’t throw away the earth if it’s not lumpy or untreated or contaminated. But instead show there’s actually no reason not to somehow plan that earth back into the construction project”, Thomas argues.

One such project where such experience of urban development was applied to a single but immense project is the double high-rise at Q5 in Graz Reiningshaus, Austria. He tells us, “there was a lot of gravel very close to the surface and that’s all material that you can build with and which you can do straight away. You can set up a sieve, a mobile crushing plant, a mobile excavation process and build with the materials on site.”

So that’s exactly what they are doing. This ongoing urban development project will create living space for 10,000 people on the 100-hectare site of a former brewery. forschen planen bauen is focusing on creating an example or a role model for the “dismantling and earthworks with maximum added value for building construction at the entire area”.

The Proof’s in the Pudding

Proving that this is a promising future for construction isn’t difficult with numerous successful projects under their belt:

Case Study: Seestadt Aspern

The urban mining project that took place in Seestadt Aspern near Vienna. Spanning 240 hectares, this was one of the world’s largest urban development projects. In an article for Atlas Recycling, a book put together by the German publication Detail, forschen planen bauen reported that “more than one million tons of material was locally processed and used in the construction of the first 3,000 apartments”. With the help of a well thought-through logistics system between the plots, virtually all of the excavated soil was re-used on site. Not only are they using local resources, it is thought this circular construction process also saves over 100,000 heavy-duty truck trips in the city area. More details about Seestadt Aspern can be found here.

Case Study: Biotope City

Once again situated in the Austrian capital, the Biotope City is a mixed settlement with offices, a school, nursery, shops and 600 apartments. All of this is being built on the former Coca-Cola facility which was “50,000m2 of sealed surface”, as Thomas describes it. But they’re turning things around with the help of urban mining “used to support the goal of creating a resilient habitat that would adapt to the consequences of climate change and allow for high levels of biodiversity in the city”. By using secondary raw materials, the green facades, green roofs, and unsealed green spaces can retain more water. The added value and the rescuing and reusing of structural components was achieved through a “cooperative network of socio-economic enterprises”, named BauKarussell, Thomas explains. This is a network founded by Thomas in 2015 for creating added value through dismantling by employing long-term unemployed people.

Thomas is convinced that “these are enlargement models that we need to pursue further”. And quite rightly, given the multitude of benefits for the environment, for us and for our buildings. He continues, “It’s not about being climate neutral, but about being climate positive – building structures so that they have a bigger effect, a positive effect and which transform our world, our built environment, for the better.”

Urban Mining in a Nutshell

Does circular construction mean round-roofed buildings? Are we going to be mining for gold rings? Can we use urban mining to get rich quick like Bitcoin mining which is all the range in 2021? Not quite. While these are interesting ideas, circular building and urban mining have a much more significant meaning for us and the future of our climate. Using urban mining to change the way we build, transforming these processes into circular ways of working and making our buildings and our cities more sustainable, is the way forward. So, let’s leave buildings standing a little longer and implement the 3Rs to give them a face lift rather than demolishing them all in one fell swoop.

Interested in finding out more about more sustainable building materials? Why not check out our guide!