How does the design of public spaces influence mental health? Could urban design reduce isolation and loneliness and increase accessibility and mobility? “Rosario is also its older adults”, a pilot project in Rosario, Sante Fe, Argentina, taps into the hidden potential of inclusive cities – project leader Ignacio Foyatier shares his findings. This article was co-authored by Rocío Suarez Ordoñez, psychologist, president and co-founder of Kozaca.

The life expectancy of the world population is increasing. It is expected that by 2050, the population over 60 years of age will double1. As of today, older adults represent 15% of the Argentine population, and it is estimated that by 2050 they will reach 25%2. Currently, most cities are not prepared or designed to accommodate the physical limitations of older adults. As we age, our cognitive and executive functions are diminished and present a challenge to living independently.

Neuropsychiatric disorders represent 6.6% of total disability in older adults. 15% of adults aged 60 and over suffer from a mental disorder, radically impacting public spending on healthcare and treatment3. Older people are the most likely to be affected by dementia, which is accelerated by reduced mental and physical stimulation, and loneliness. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the number of people living with the disease will be close to tripling by 2050, implying a high demand for public health services.4

At the same time, in most societies, there are no public spaces designed for their inclusion. Urban design unintentionally excludes the active participation of older adults. The shortage of ramps, well-lit spaces, and designed accessibility for the elderly demonstrates that the isolation of older adults is not elective but consequential of a lack of inclusive design and urban planning.

How can urban design reduce isolation? How will we face the coming pandemic of mental illnesses resulting from long days of quarantine and loneliness? For older adults, it results in significantly longer periods of time in solitude. Consequently, older adults become increasingly more prone to illnesses associated with poor mental health and a sedentary lifestyle.

Rosario is also its older adults has become a pilot and benchmark experience for the use of public spaces in the city for the elderly and people with reduced mobility. It has been recognized by the Municipality of Rosario as an Activity of Municipal Interest according to Decree No. 58.086.5

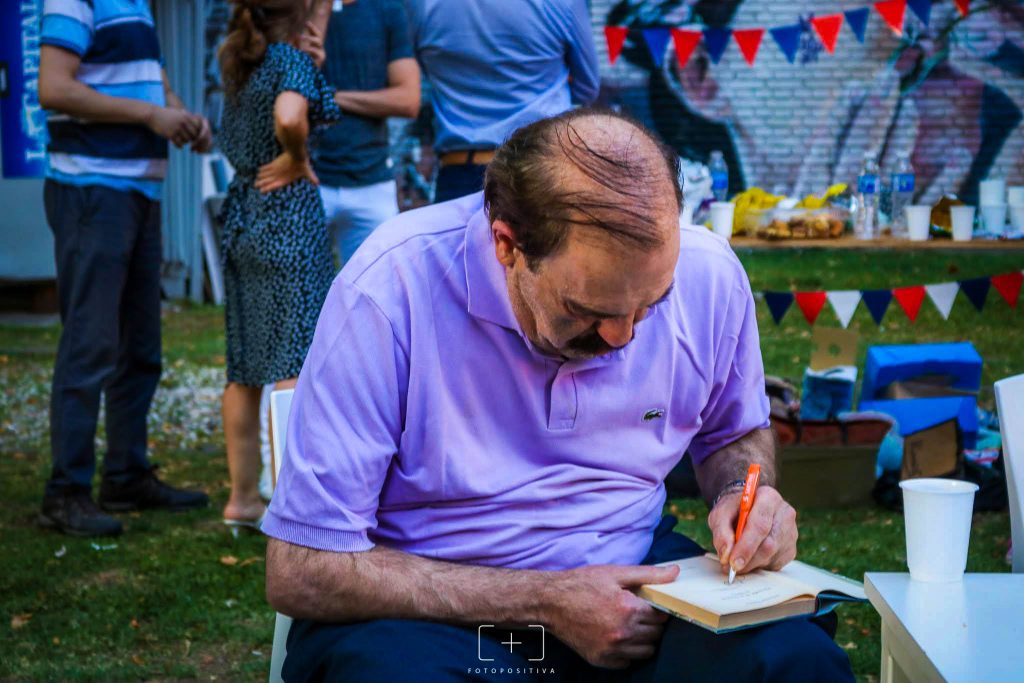

The project sought to design urban spaces and equipment focused on older adults. The main objective of the intervention was to invite older people to have access and activities6 in the public spaces of the city according to their needs. During the journey, there were game cards, Jenga towers, darts, and memory games available to use. Additionally, there was a whiteboard to write down ideas on how we collectively imagine our city, books, snacks, and drinks. Most importantly, there was easy access to chairs and tables for older citizens, where they could enjoy a simple conversation.

Small activities like these in a green space prevent cognitive deterioration and encourage light exercise and mental stimulation. These can help prevent the onset of dementia and manage symptoms, improve cognitive abilities, build physical strength, increase confidence and independence, and reduce feelings of isolation.

This pilot project goes to show how public environments can enhance social ties, produce adaptable spaces for interactive mental stimulation and enforce community building. More than 50 seniors participated and shared their feedback and opinions through surveys and a “public whiteboard” where the participants and passerby could express their ideas about what makes a good public space.

Take-Aways for Next Editions

The surveys7 were open to everyone who wanted to share his or her ideas. 58 surveys have been answered, with respondents aged from 22 years to 84 years, 64% being female, and 36% being male.

The respondents show a great interest in promoting quiet, accessible, and safe meeting spaces – spaces for having conversations, spaces without noise, places to chill and relax, and places for meeting friends. This includes better accessibility for the elderly, public events, level pedestrian crossings, sidewalks in good condition, and more benches and gaming tables, among others.

92.3% of the respondents would return to participate in this type of event weekly, while 93.1% would go to places designed for the elderly, if available. 60% of respondents want to have outdoor events, like cinemas, festivals, and art. 51% wish to have quiet spaces for meeting and adult tours inside the city. This demonstrates the great interest of adults in participating in public space and, on the other hand, the lack of consideration towards them in the design of public spaces in the city of Rosario.

Final Reflections

Measures that were put in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19 have generated anguish and frustration in many, causing (in some cases) emotional destabilization, which brought along both physical and psychological symptoms in people of all ages. The reduction of physical activity leads to sleep problems, insomnia and daytime sleepiness, which has already been demonstrated in different investigations8. An increased cognitive impairment due to having stopped carrying out cognitive stimulation activities, workshops, gatherings, group therapies, and volunteering affected the emotional and mental state, with an increase in depressive symptoms9 due to a lack of contact with the social network and loneliness. Loneliness increases the risk of a sedentary lifestyle, cardiovascular diseases, inadequate nutrition, and the risk of death.10 The quantity and quality of sleep can also be affected in people who suffer from loneliness, causing greater fatigue during the day.11

At the same time, the pandemic has confirmed that human beings are social creatures. The loneliness and confinement that we feel during quarantine is part of an episode that humanity has rarely ever collectively experienced. It is hugely important that conducive public spaces as meeting places and recreation are included in the daily lives of citizens, as they allow for activities that decrease cognitive decline while also allowing for social distancing.

Urban parklets show that quiet and accessible meeting spaces are more important than roads or car parks. Car space needs to be redistributed to have enough distance between customers in open-air markets. The value of active mobility, where safe social distancing can be achieved, has revealed the urgent need for adaptation in the design of sidewalks to avoid crowding. Special hours were established for the vulnerable population. Bicycle paths have begun to pop up across cities as mobility alternatives to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

These urban interventions in response to the pandemic further validate and emphasize the necessity of the findings of Rosario. As urban planners, we must begin to implement design changes in our cities to develop behavioural changes that can facilitate the activities of older adults.

This is just one starting point in designing suitable spaces for our older adults. When we furnish our cities with urban equipment catering to older populations, we create spaces promoting psychological well-being for all urban dwellers by promoting human contact and social interaction.

“We should recognise that every detail in the physical composition of the built environment has the potential to deliver comfort, convenience and connections to others. We have to create a state of mind.”12

1 United Nations – Department of economic and social affairs (2019) World Population Ageing 2019.

2 Centro de Economía Política Argentina (2019) Informe sobre situación de las personas mayores.

3 World Health Organization (2017) Mental health and older adults.

4 Rooney, K. (2019) The parks of the city of Bilbao offer mental training circuits for older people.

5 Municipal Council of Rosario City (2019) Decree No. 58.086. Retrieved from https://www.rosario.gob.ar/normativa/Decree No.58086

6 All these activities were carried out with the help of Physiotherapists and Staff of the Institute of Cognitive Neurology Foundation and Red-I Staff

7 Own source. 58 surveys have been carried out. The age range of the respondents is from 22 years of age to 84 years, with 36% male and the remaining 64% female.

8 P. Moreno, C. Muñoz, R. Pizarro, S. Jiménez. (2020) Efectos del ejercicio físico sobre la calidad del sueño, insomnio y somnolencia diurna en personas mayores. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol.

9 Y. Huang, N. Zao. (2020) Generalized anxiety disorder depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 epidemic in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. MedRxiv.

10 P. Eng, E. Rimm, G. Fitzmaurice, I. Kawachi. (2002) Social ties and change in social ties in relation to subsequent total and cause-specific mortality and coronary heart disease incidence in men.

11 Sacramento Pinazo-Hernandis (2020) Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on older people: Problems and challenges. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol.

12 Sim D. (2019) Soft City. Building Density for Everyday Life. Island Press