Implementing spatial changes that benefit citizens isn’t a straightforward process. In many cities, there’s not a process for it at all! Or is there? The case of Muscat, in Oman, shows us that it may be disadvantaged citizens rather than authorities who possess the real change-making power. We talk to Rowa Elzain and Shaharin Annisa, who share their lessons in facilitating cooperation between the two, and how this has proved to change mindsets for actors in urban design – including their own.

Sustainable cities should adequately support their most disadvantaged citizens.

Listening to people’s diverse experiences is key to identifying and plugging gaps in provision, creating equitable access, and designing-in social and urban resilience. But these voices are frequently left out of decision-making processes.

In Muscat, Oman, this is changing, thanks to a team of friends who have achieved something novel: getting the city’s leaders to listen to their citizens.

Discovering Muscat’s Empowered Communities

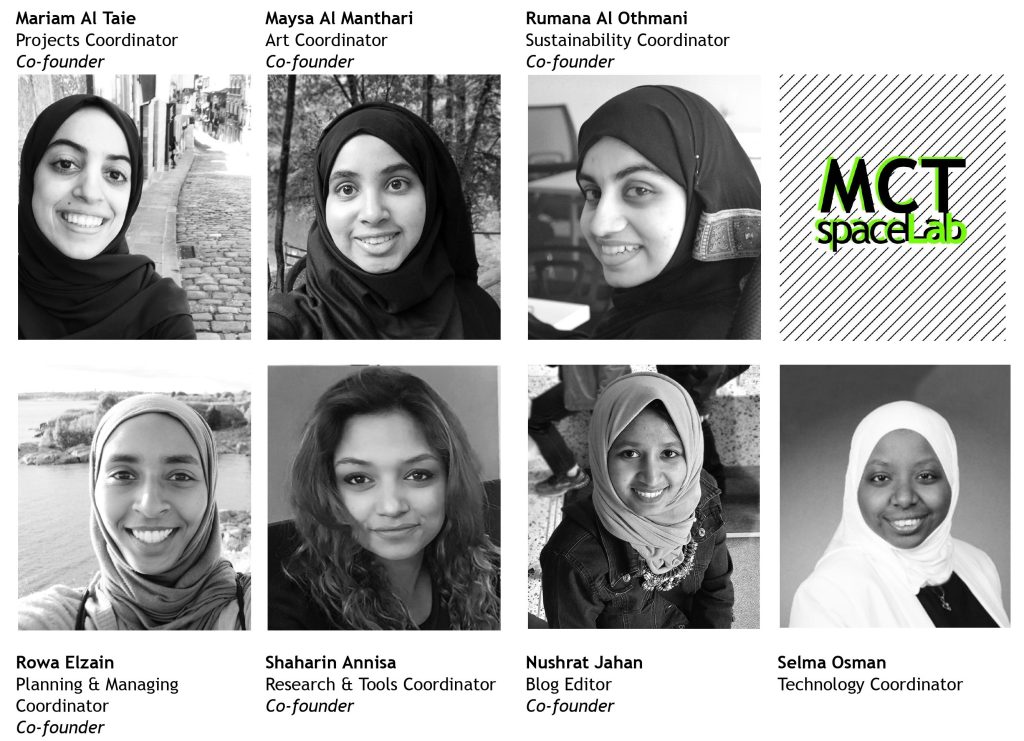

Officially launched in 2017, the concept behind non-profit grassroots initiative MCTspaceLab began as Rowa Elzain’s master’s thesis. She drafted in the other five founding members to assist with her research, and they never stopped!

The group asked people in Muscat about their lived experiences of urban spaces: how they use it and for their needs and wishes.

It was the first time many of the participants – especially women – felt that their opinions on urban design were heard. Until then, they thought this was a matter only the municipality could weigh in on.

Unbeknownst to them all, these communities were already influencing the use of local spaces, having set up plenty of activities for informal education.

This included a building for children of both genders to engage in further education after school, and to act as a learning space for women, where they can read and exercise together.

They hadn’t set out to shape their outdoor environment so didn’t recognise their own capabilities to do so. In fact, what motivated them to act was the want to create opportunities that benefit their children, especially in lower incomes communities and those with limited facilities.

As a result, “they had a very strong sense of community, and managed to achieve a lot in comparison” to wealthier parts of the city, Rowa observes.

Lessons in Community Engagement

In terms of communicating ideas across multidisciplinary actors in urban design, we can learn a lot from MCTspaceLab and the communities they’re working with.

Initially, engaging the people was not that easy, Rowa recalls. “You’d talk to them, you’d send them something, and then you’d get a response weeks later.” This was the first time the people were asked for their opinions on their city, so they needed to learn how to respond, what was expected of them, and to trust in those asking for their opinions. Which meant the MCTspaceLab crew had to prove it.

Leading workshops, they shared inspiring examples of the uses and looks for urban spaces. Then they moderated discussions to encourage participants to come up with ideas of their own, based on their needs.

We’re talking to people and telling them they can take ownership of their public spaces, that communities can do such a thing.

Shaharin Annisa

To begin with, they focused their work at the narrow end of the wedge; building on existing concepts, they started with activities for children.

In a MCTspaceLab summer holiday workshop, young girls were asked to draw what they thought a public space should be. Requests for pavilions and other spaces to be sociable and safe revealed much about their needs.

It’s Not One Size Fits All

For the idea to really take off, MCTspaceLab had to demonstrate respect for cultural sensitivities, especially among more conservative neighbourhoods.

That meant separating sessions into smaller groups along gender lines – for women and men, girls and boys.

“Of course, it’s tough to have to repeat things four times,” Rowa acknowledges. “But when you function the way they function, you can extract more information that is beneficial to everyone.”

Especially as this clusters traditionally dominant and quieter perspectives, Shaharin Annisa adds: “The moment you separate men and woman, you see that the women have more of a voice.”

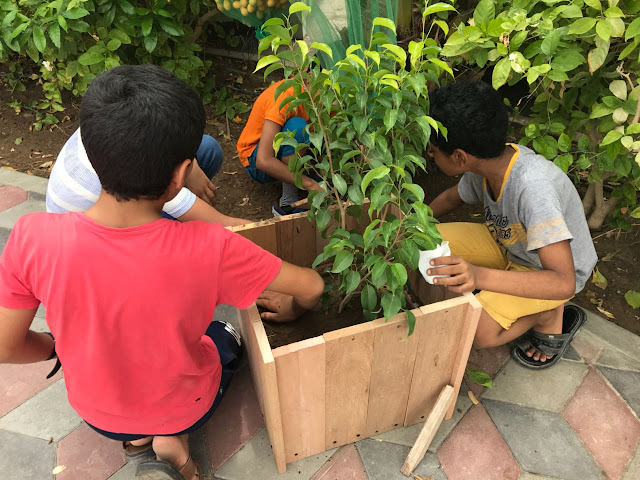

At first, adult males were a little hesitant to join discussions about what the municipality legally offers and how this correlates with their need. That is, until they saw their sons participate in their own workshops.

When they saw that the kids were doing things with their hands, and they’re learning from us, this is when we could start a discussion with them.

Rowa Elzain

Real engagement has to be on the terms of those we want involved.

Why Facilitation Matters

The community offered plenty of ideas for their urban spaces. But the team noticed how individuals still felt powerless to assert their wishes.

Running informal social and educational activities is different to implementing spatial transformations. That’s much more complex and requires municipal input.

“There is a need for somebody or a group like us to take the role of a facilitator,” says Shaharin. MCTspaceLab’s real success is mediating conversations between the community and Muscat’s decision-makers.

Challenges of Being Pioneers

MCTspaceLab is a volunteer network. In their day jobs, each member is a practicing urban planner or architect. They know first-hand that planners persistently fail to produce the kinds of urban environments communities really want, so the team understands the need to converse in the professionals’ own terms, too.

“It involves a really different kind of participation,” Shaharin tells us. “It’s about creating awareness. We have to tap into it.”

But persuading the city to see the ideas through can be tough going. This is why MCTspaceLab acts as an intermediary, lobbying Muscat’s municipality on behalf of communities to implement peoples’ proposals.

“In Oman, we are still kind of ahead of our time,” Rowa says.

But that makes things tricky: there is no precedence for community-led initiatives having the backing at the city level in Oman, which means there’s a lack of streamlining in the process – from concept to design to approval to implementation.

One early hiccup came from both the citizens and authorities clinging to the ideas they really wanted to push – and having expectations of what the other should and shouldn’t do.

It took MCTspaceLab around five years to navigate through these loggerheads. And at least the three parties – community, municipality, and MCTspaceLab – are now at the table, having these conversations.

Acting, as they are, outside of any affiliations to institutions or agendas, the group’s credentials as impartial mediator counts for a lot.

We’re impartial in the eyes of both state and the community. That’s a way of starting the process of trust-building. They can talk to us. I think that’s quite important.

Shaharin Annisa

It’s clearly worked, as the city seems to have spotted a chance to share the burden of neighbourhood planning.

“They want to branch a law out of it to enable communities to take responsibility for their outdoor spaces and develop it by themselves,” Rowa explains.

A wise move for municipalities working with stretched resources.

Creating a Public Image… and Impact

Public exposure is important in sustaining MCTspaceLab’s public image as an impartial entity and building further legitimacy among Muscat’s communities and urbanists.

This didn’t happen overnight – or by chance.

The team worked hard to find a voice suitable for multiple media: updates on Instagram, blog posts, radio shows, lectures, speaking at conferences, etc. Each is a window into their activities and impact.

“We had to prove ourselves, that we are capable, we are doing things,” Shaharin reflects. “But this was good, because then we found that we had a lot of information prepared in different languages.” Not only in spoken languages like Arabic and English, but in diverse formats that target a variety of stakeholders.

Real Life Examples

All this points to real change in Muscat – like the introduction of more green open spaces.

It started with MCTspaceLab’s analysis proving that the city had just one small park per 10,000 inhabitants.

With their help, the community was able to identify suitable plots that could serve as public spaces and, where these were earmarked for residential or commercial development, carry out legal procedures to repurpose their use.

As urban designers, the MCTspaceLab team could help people design these spaces to suit their wishes. From there, the community took over, finding the funding, donating trees, and planting the park themselves.

In another case, a community acquired land from the city administration to build a mosque. Later, they expanded the compound to include a community hall and school. True to the original motivations the researchers observed, this created additional learning opportunities for local children but also safe, inclusive, social spaces for all residents.

For Rowa, the most important influence MCTspaceLab “had is that we kind of opened their eyes to the fact that they need public spaces, not just buildings, to interact”.

It has even gained the team some international attention, having since worked as a local consultant under UN Habitat on an project relating to urban planning law.

Progress Takes Time

Everything MCTspaceLab achieves is thanks to the team members’ personal commitment to Muscat’s communities. They do this alongside full-time jobs – without funding.

In the early days, Rowa quit her job in Germany to focus on establishing MCTspaceLab in Oman. It’s still operated between the two countries.

Shaharin admired this commitment to get the initiative off the ground. “You need somebody like this, who really has an interest a stake in the project, research-wise, who can drive it.”

But after a year with the initiative not bringing in any money, Rowa returned to work and the team decided that MCTspaceLab should be allowed to develop organically.

“We realised things need time, and we can do this as required,” Rowa admits.

They also recognise the importance of being able to walk away, Shaharin points out.

“So many times, we wanted to quit. When the stress level is very high, you need to physically detach yourself from that context, and that gives you the energy to continue.”

“It is really because we work in a team,” Rowa adds. “When two are frustrated and they take a break, the other four step in and take over, which is beautiful somehow.”

Money Isn’t Everything

This is a lesson they learnt in time – and that’s not the only one.

MCTspaceLab’s original appeal for funding failed. Starting out without capital presented a frustrating struggle. But members of the community clubbed together to put forward the money needed to implement their ideas in the neighbourhood.

First, it was citizens’ skills that rose up to create the change they envisaged. Now, it was because of their commitment and drive. They had just needed help to see that they could do it.

This self-reliance is MCTspaceLab’s legacy. “We have to really rely on the communities to take action by themselves to continue,” says Rowa. “This is what should happen at the end of the day. It’s not us providing but rather us guiding; if we hadn’t had a shortage of money, we would have failed to reach this point. Now I see the beauty in it.”

Growing a Passion Project in a Nutshell

Possibly MCTspaceLab’s greatest lesson for other CityChangers is that “you don’t have to have the support of everyone to push an idea”, Rowa Elzain concludes. “You can test it out with whatever little money you have.” And we cannot use cultural barriers as an excuse not to act – there is always a solution.

The final word from Shaharin Annisa is just as poignant. She reminds us that change isn’t only the plaything of the powerful, and that big cities can learn a lot from local communities, whatever their background: “Unlike many other processes in the Global South, these communities are already doing something. So, the potential is there.” Planners need to listen. And where they don’t, it helps if someone can step in to facilitate.