All of us are pedestrians. We’re born with all we need – legs – to participate and use them throughout our lives without even thinking. Walking makes our lives more convenient, enjoyable, affluent, and worry-free. With so much to gain, the benefits of walkable cities are about more than just a stale old argument against driving. Keep reading to find out why foot-friendly cities are the right step to a brighter future.

It’s an unavoidable fact: we travel by car far more than is necessary. In England, 23% of journeys are under 1 mile (1.6 km), yet only 25% of people walk them. Barcelona, a beacon of walkability, still dedicates 60% of street space to cars, when just 14% of its residents regularly get behind the wheel. Hopping in the car has become the norm because cities are designed to fit the use of motors more than the needs of people.

However, driving is often far from the best option. Citizens and decision-makers are starting to wake up to the benefits of infrastructure with walking at its foundations; in a 2020 YouGov survey across 21 European cities, 74% of responses – including drivers – supported the reallocation of space from vehicles to people-centric transport. But why?

Maybe they’ve read the CityChangers case for car-free cities.

Or maybe they’re aware of the robust and manifold benefits that arise from making space for pedestrian activities. With the economy, public health, transport systems, political office, and equity all set to gain, it’s a convincing case for taking a stroll.

Money Talks When People Walk

Let’s face it, fiscal incentives lubricate the change process. Walking is good for business.

Despite assumptions that slashing vehicular access and parking negatively impacts trade, pedestrian-oriented areas bring in the big bucks. The density of outlets tends to be higher, allowing shoppers to ‘bounce’ between stores and spend more. Up to 40% more in London, while New York City has seen a rise in retail above 170% since rezoning parking spaces for pedestrian purposes. Cha-ching!

It’s a virtuous cycle. More paying customers means fewer empty stores, so high streets thrive, creating jobs. That’s in addition to the workforce taking care of the design, construction, and maintenance.

Every car off the city’s streets makes room for 20 pedestrians – or space for cafés to have tables outside, increasing scope for patronage. It also creates a safe space for children to play, interact, and develop friendships and social skills.

Shops, restaurants, and those who live above them, attracted by safe pathways and accessible amenities, pay rent. Up to $1,200 a month more than in non-walkable neighbourhoods.

Throw a pebble into a pond and see the ripples spread. Throw in a coin and the same happens. Walkable City, Seoul’s creation of a people-oriented centre resulted in a more mobile population[1], which radiated outwards, revitalising other districts of the city with their presence and purses. If a city boasts interconnected walkways, people will tread them, and they’ll bring coin. It’s as true for boosting tourism as it is shopping and entertainment.

What about the street as a workplace? Cities depend on those who deliver our post, takeaways, and newspapers by foot. We turn to food trucks for lunch and avoid the swarm of charity fundraisers. Wider paths, better lighting, drop kerbs, fewer vehicles, benches to rest on and trees to shade under all make their everyday working lives better. And as regular walkers take 43% fewer sick days off work, employers, health services, and insurers all benefit from cost savings.

Mixed Modes Offer Better Transport

In 2020, Europeans spent five-and-a-half days sitting in traffic. Not fun. It makes us irritable and late. Emission levels are unsafe for breathing in at least 80% of cities and around 15% of all greenhouse gases are attributed to transport. Seven million people die from air pollution each year. It’s clear we need a change.

Putting amenities within reach ‘displaces’ travel choices: if a local bar is within walking distance, why drive? No parking, no fuel costs (or consumption), no need to find a designated driver willing to stay on juice all night, and no waiting for a bus or taxi. Complete independence.

Cities are big places. Urban sprawl has led to a reliance on cars. Mário Alves, Secretary-General of International Federation of Pedestrians, told us that “the distances become very, very large, and people cannot walk. So, they start taking the car… they start making larger cities.” Unless we break this cycle, we’re setting a trap for ourselves.

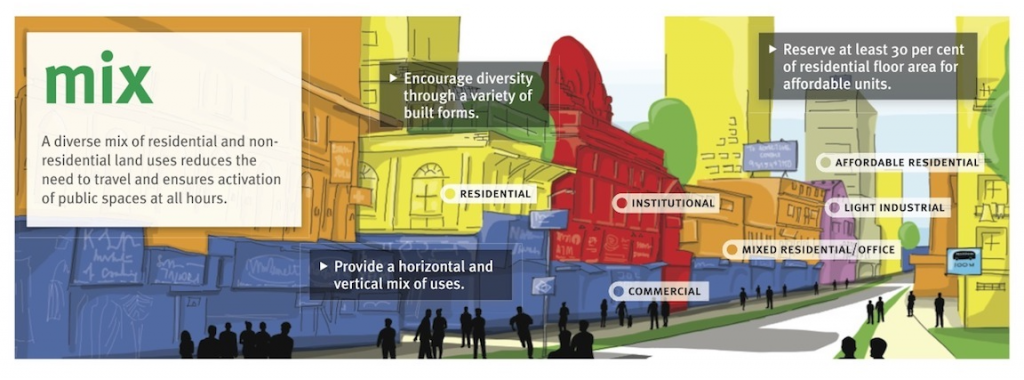

Compact cities provide an answer. However, where facilities remain decentralised, walking alone isn’t feasible. Municipalities where public transport and walkability are complementary work for a reason.

Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) advocates for dense, walkable neighbourhoods served by clean, efficient, reliable public transport accessible within a 5-minute walk. It makes sense: a PT network that requires citizens to take private motorised means to and from end stations is not fit for purpose.

“While walkability benefits from good transit, good transit relies absolutely on walkability.”

Jeff Speck[2]

Swapping away from private modes does increase demand – and therefore wear and tear – on public transport, but also ticket revenue, feeding cost-recovery and reinvestment. It streamlines traffic, reduces stand-still congestion and accidents, and speeds up journey times. Roads become, in a word, efficient: ironically, drivers – those who really must go by car – have much to gain from foot-friendly policy.

Politicos, Pay Attention

It requires political commitment – bravery, even – to challenge the status quo. Alves explained that the car lobby is slipping away as people vote for initiatives that welcome greener policy. Urban sprawl, road-building and new bridges are no longer the answer to meeting the demands of rising populations. Political might thrown behind walkable areas is raking in the votes.

Mayor Miguel Anxo Fernández Lores is a notable example. He pedestrianised Pontevedra city centre in Spain in his first few months in office, reversing a residential exodus. Now, children walk to school unaccompanied. People can talk without shouting over the hum of traffic. No pedestrian fatalities have been recorded since 2009.

Lores has been elected mayor continuously since 1999. “Some people can’t stand you ideologically, but value that you’re doing things well”, he said. Progressive politicians do well in elections, it seems.

To find out more about Pontevedra, you should check out the CityChangers interview with Xosé Cesareo Mosquera, the city’s head of infrastructures.

Living in a Healthy Body and Happier Community

Unsurprisingly, walking is good for us. It helps our physical health, longevity, and mental wellbeing. Regular legwork can save up to $1,900 in annual healthcare expenses per person – see the facts for yourself.

In the elderly population, a regular stroll has proven beneficial in cognitive processing.[3] This is also the age group statistically most likely to suffer in traffic accidents as pedestrians, which leads to fear, and so a decline in mobility. Isolation follows. This can be avoided.

Foot-friendly neighbourhoods provide a safe space where the anxiety of crossing a busy road is replaced by a setting suitable for mingling, sometimes people’s only chance to be sociable.

Alongside interpersonal relationships, a study in the Republic of Ireland[4] found a city’s walkability increases social capital by as much as 80%[5]: that’s a bolstering of shared values, trust, participation in volunteering, political involvement (think Fridays for Future), and sense of identity.

If Rotterdam’s ‘The Neighbourhood Takes Charge’ project is anything to go by, that’s a further cost saving to the local administration.

It began street cleaning and graffiti removal in a move to make the routes more welcoming to walkers. This led to a dramatic reduction in drug crime (30%), vandalism (31%) and burglary (22%).[4] Increasing safety and confidence, such schemes lead to people walking more – and enjoying it.

All this adds up to a happy, cohesive, cost-effective community. We defy anyone not to be impressed. And the best thing is everyone benefits.

The Long Walk to Equity

Dirty air has dire social consequences.

It is becoming more common for schools to close due to smog and for parents to keep kids home to protect their health.

The more frequent a child is absent, the lower their attainment level and the higher the likelihood of dropping out of studies. This creates a void in attainment and life-long opportunity.

What about childcare? As we’ve seen with home-schooling during the coronavirus pandemic, this is problematic for gender disparities; women in the US were three times more likely than men to provide childcare. And where pollution is greatest, inequalities in the labour market are highest.

Walkable cities are cleaner cities. Therefore, they’re more socially just cities.

But is walkability a barrier to fairness? Guru of walkability Jeff Speck warns of the association walkable neighbourhoods have with elitism. It’s easy to see how. The ‘Walk Score’ tool claims easy access to amenities, entertainment, and green spaces has a monetary gain: each point “is worth $3,250 in home value”. Cue alarm bells of gentrification – and inequity.

It needn’t be unbalanced. Low-income earners who own property are just as likely to cash in. Cue upward mobility. Even if not, TOD offers more solutions by allocating space for affordable housing in accessible communities, offsetting the traditional effects of gentrification-based displacement regardless of class, income, or cultural background.

Foot-friendly cities are a powerhouse for combatting transport poverty, itself exacerbated by car dependency. Driving is costly, walking is free. If jobs, amenities, relationships, and other building blocks of a dignified lifestyle are out of reach, we encounter a schism of affluence and breakdown in independence. This is such a prominent issue that evocative terms have been coined for the obstruction of access to sustenance (food deserts) and health services (care deserts).

In our streets, people of colour and anyone over 65 are 54% and 68% more likely to be struck by vehicles, respectively. Low-income earners are also more at risk. For a sobering look at the inequality of safety for people of colour in our cities, read this article.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) campaigns for safe spaces in the built environment, where youngsters have opportunities to be active. It’s a matter of health inequalities. While obesity levels in the USA are declining overall, “black high school girls are two-and-a-half times more likely to be obese than their white counterparts”. The NAACP’s answer is walkable urbanity, says Director of Health Programs, Niiobli Armah:

“Regardless of what community you live in, you should have access to healthy eating and active living.”

A walkable space is a safe space, an active space, and a more equal space.

The Case for Walkability in a Nutshell

Proponents of walking are not as plentiful or outspoken as lobbyists for cars, cycling, and public transport. This is changing, and it’s important to see how these multi-modal means can work together to meet the needs of citizens rather than focus on competing for dominance.

We may have a long way to go before whole cities, rather than silos, become fully navigable by foot, but with innovations, investment, and political support the groundwork is set. And we’re already seeing – and feeling – the benefits.

[1] Shafray, E., & Kim, S. (2017). A Study of Walkable Spaces with Natural Elements for Urban Regeneration: A Focus on Cases in Seoul, South Korea. Sustainability, 9(4), 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040587

[2] Speck, J. (2012) Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[3] Alhamidi, Reema; Naydenova, Edelina; Dahlin, Katherine; Rush, Jason; Gonzales, Margarita; Ryan, Kevin; Harmon, Laura; Schaeffer, Marcel; Iliesi, Bianca; Silverman, Laura; Jones, Brady; Todoroff, John; Mulsoff Brown, Megan; and Wells, Adrian (2013). Aging in our Communities: Six Case Studies of Neighborhood Walkability in Clackamas and Washington Counties, Oregon and Clark County, Washington. Asset Mapping: Community Geography Project. 3. http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/ims_assestmapping/3

[4] ARUP. (2016). Cities Alive: Towards a Walking World. https://www.arup.com/perspectives/publications/research/section/cities-alive-towards-a-walking-world

[5] Sinnett, D., Williams, K., Chatterjee, K., & Cavill, N. (2011). Making the case for investment in the walking environment: A review of the evidence. Living Streets. https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/971643

[…] the healthier, the happier you are. After all, the fact that in 2020, Europeans spent on average at least 5.5 days stuck in traffic (over the whole year, not at one time) can’t be doing a lot for them mentally or […]