Changing the infrastructure is never an easy task. A lot of thought goes into designing an efficient transport system – but does it consider all modes of transport? Learn about the most important elements to consider when on a mission to make your city more pedestrian-friendly: from footpath design to intersections, from accessibility to the scenery.

If you’ve read the CityChangers’ article Walking: Facts & Figures, you’ve probably noticed the reasons why people don’t walk. To refresh your memory, they include:

- Fear for personal safety

- Traffic noise and fumes

- Poor path maintenance (or no footpaths at all)

- Unpleasant aesthetics en route

- Lack of lighting

It’s good to keep these causes in mind, in order to improve the situation and implement the solutions into infrastructure.

Key Elements of a Pedestrian-Friendly Infrastructure

Here are some of the main elements to pay attention to when transforming the infrastructure into a more pedestrian-friendly one:

a) Footpaths

Let’s start with the obvious one – safe and functioning sidewalks. The right design requires a lot of planning, researching, and organising.

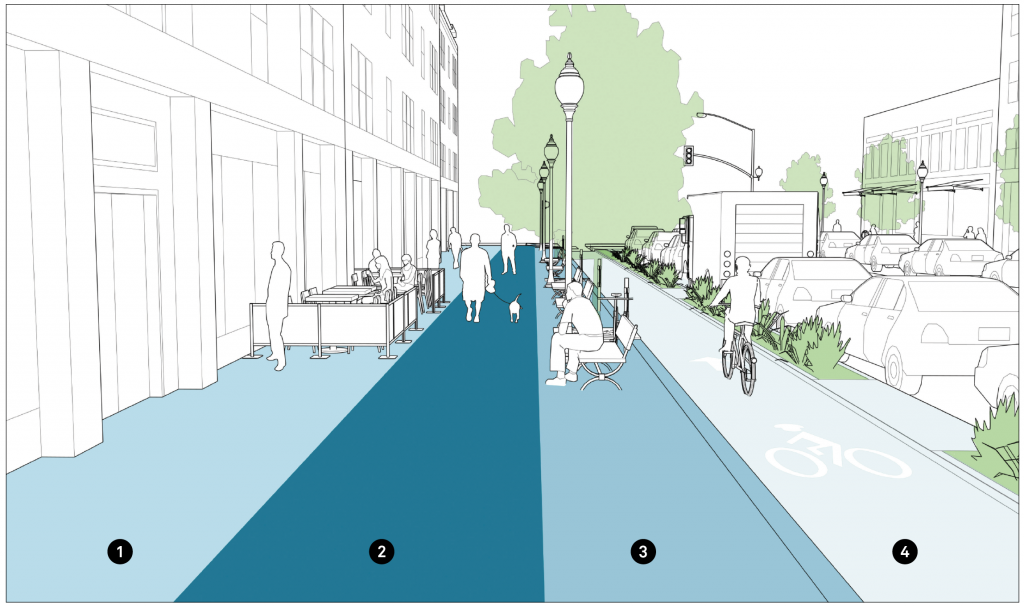

First and foremost, perfect sidewalks consist of four zones (see depicted model below):

- Frontage Zone: The zone provides a bit of space between the Clear Path Zone and buildings (entryways, sidewalk cafés, etc.).

- Clear Path (also known as ‘the throughway zone’): This path provides safe and sufficient space for pedestrians. It should be 1.8–2.4 m wide in residential settings and 2.4–4.5 m wide in areas with heavy pedestrian volumes.

- Street Furniture Zone (also known as ‘the furnishing zone’): Here, space for landscape and street furniture is provided, including lighting, benches, newspaper kiosks, transit facilities, utility poles, tree pits and cycle parking.

- Buffer Zone (also known as ‘the edge zone’): It separates the road from the sidewalk. It can include different elements, such as curb extensions, stormwater management features, parking, cycle tracks etc.

Next, there are different types of sidewalks to be considered, each with its own specific needs and important elements. They include residential sidewalks, neighbourhood main street sidewalks and commercial sidewalks.

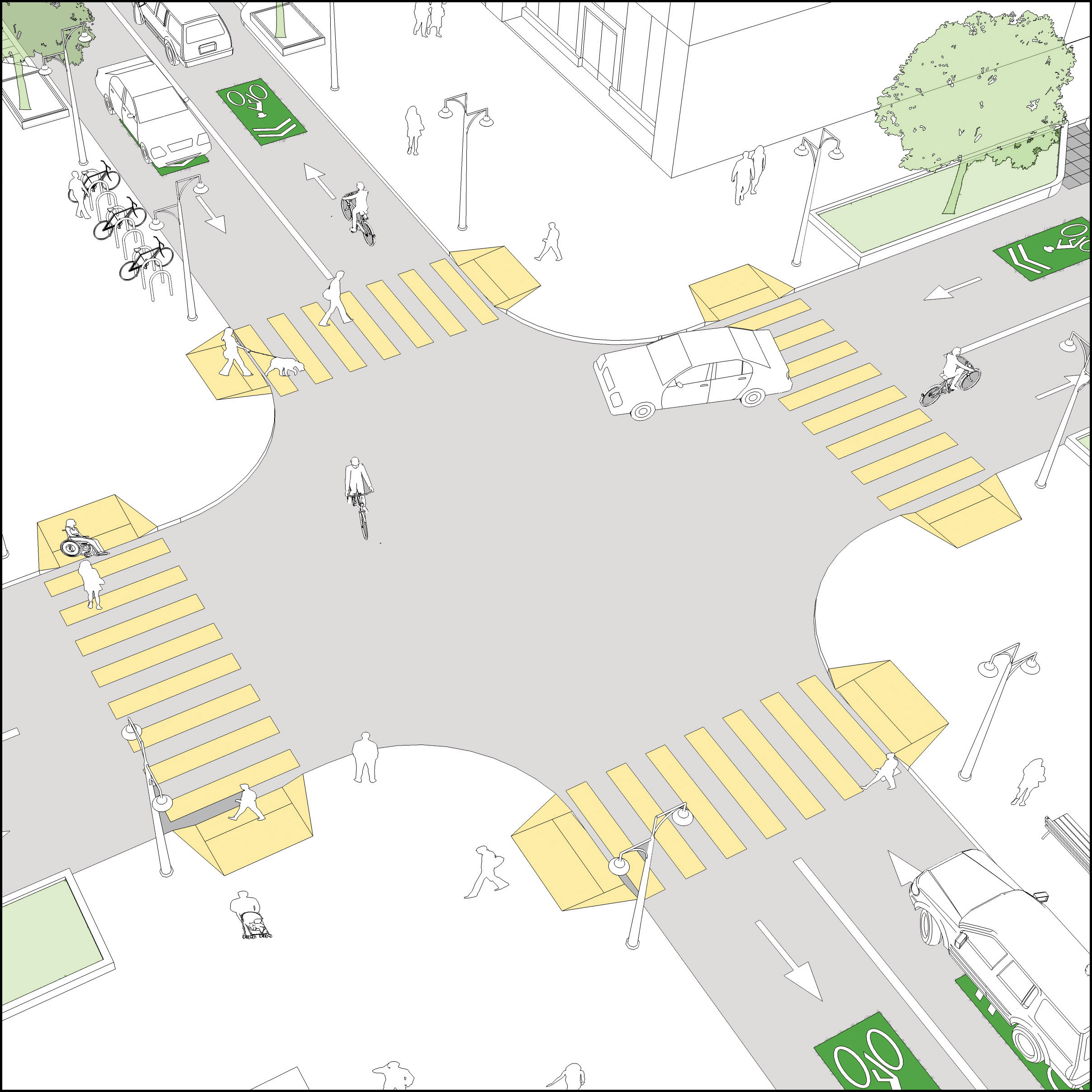

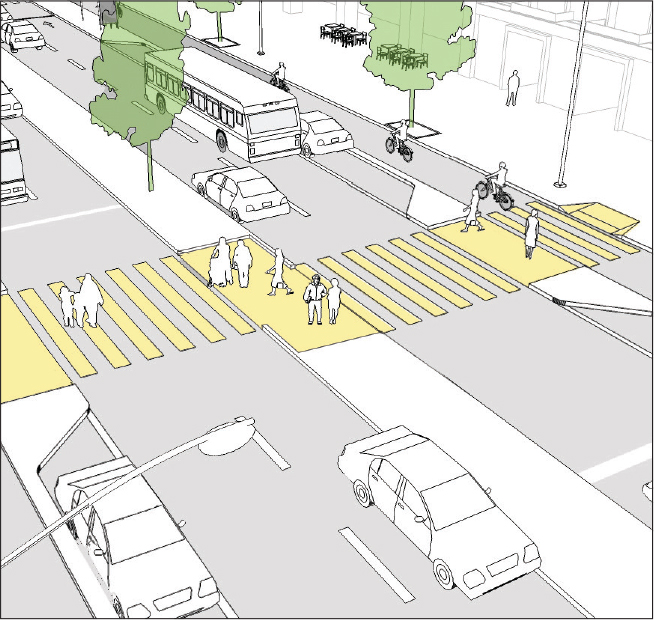

b) Pedestrian Crossing

When providing the city with a functioning, time-efficient and safe intersection for all road users, various types of pedestrian crossings can be selected. Each one is different and varies due to the different needs and characteristics of the neighbourhood. The Global Designing Cities Initiative recommends the following types of crossings:

| Crossing Type | Characteristics | Guidelines | Sketch Example |

| Conventional | – Low to high pedestrian volumes – Signalised – At intersection – Any speed of vehicles – Low to high volumes of vehicles | – Positioned as closely as possible with the pedestrian clear path – As compact as possible – Putting pedestrians directly into the driver’s field of vision |  |

| Diagonal | – High pedestrian volumes – Signalised – At intersection – Any speed of vehicles – Medium to high volumes of vehicles | – When crossing, all vehicular traffic is stopped – Only at intersections with high pedestrian volume – Provides enough space for a large number of people – Reduced waiting time for pedestrian safety |  |

| Raised | – Medium to high pedestrian volumes – At intersection – Mid-block – Speed of vehicles below 30 km/h – Medium to high volumes of vehicles | – Raised crossing – In busy neighbourhood main streets and commercial streets – Where small neighbourhood streets with slower speeds meet larger corridors |  |

| Traffic Calmed | – Low to medium pedestrian volumes – Mid-block – Speed of vehicles above 30 km/h – Medium volume of vehicles | – Use of speed bumps, tables, and cushions – Speed control elements 5–10 m from the crossing – Use of pedestrian-activated warning lights – Raised crossing |  |

| Staggered | – Low to medium pedestrian volumes – Mid-block – Speed of vehicles above 30 km/h – Medium volume of vehicles | – Only when the depth of the cut through allows full accessibility – Width of the median min. 3 m and distance to the sidewalk to not exceed 1 m – Stop bars set back 5–10 m – May include speed bumps |  |

| Pinch point/Yield | – Low pedestrian volume – Mid-block – Speed of vehicles below 30 km/h – Low volume of vehicles | – Short crossing distance at mid-blocks – Lane width of 3.5 m at the pinch point (for emergency vehicle access) |  |

c) Traffic Light Signalling

Regulations for traffic lights and signals for pedestrians vary from country to country; however, here is a mix of recommended regulations by the Inclusive City Maker and Planning and Designing for Pedestrians (a guide), creating the ‘perfect’ pedestrian-crossing traffic light system for a smooth pedestrian experience:

- You should educate yourself about traffic volumes at a specific intersection, the complexity of the intersection (from the pedestrian’s point of view), the actual need for traffic signalling, etc.

- Traffic lights should include pushbuttons or passive detection devices for pedestrians to signalise their wish to cross the street. They should be accessible to all (including wheelchair) users, no higher than 0.9 m on the support pole, should be within 3 m distance of the pavement and be parallel to the used crosswalk. Ideally, to enable access to all pedestrians, pedestrian traffic light buttons should also include integrated audible tones, and the name of the street should be written down in braille or convex print.

- Additional devices, such as animated eye indicators (eyes looking left and right to remind pedestrians to look out for vehicles), count-down pedestrian signals and enhanced pedestrian push buttons (for pedestrians with physical disabilities), are helpful to increase intersection safety.

- Duration of green traffic light should allow an average pedestrian to cross comfortably – on average, a walking speed of 1.2 m per second is used to determine the signal duration, however, using a reduced speed of 0.9 m per second is recommended to take into account the elderly and people with different abilities.

d) Accessibility

It’s important to include all pedestrians in the process of designing walkable sidewalks – they are the ones who are going to use them after all. This means the inclusion of people with different abilities, too. Providing sidewalks with ramps, pavements with useful components, installing traffic lights equipped with acoustic signals, etc., is a way to go about it.

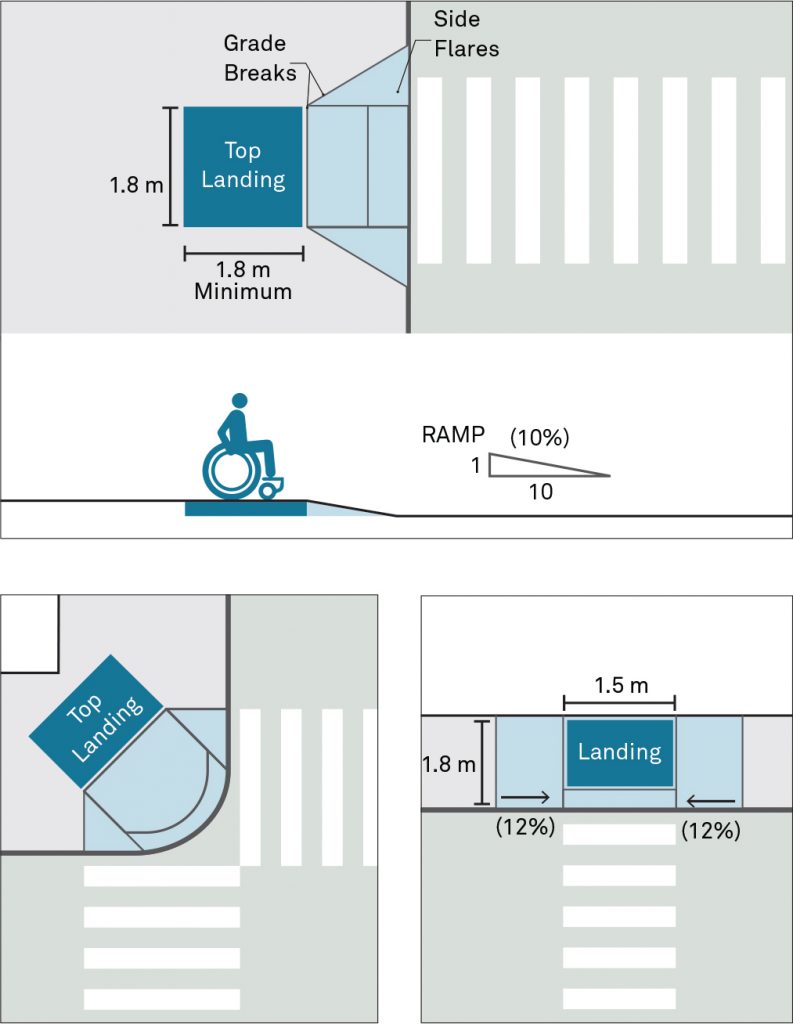

According to the Global Designing Cities Initiative, sidewalks should be equipped with pedestrian ramps for people using wheelchairs, pushing strollers, carts or heavy luggage. Ramps include three elements (see depicted model below):

- Slope: It is constructed of non-slip materials and should have a maximum 10% incline, while the width of the ramp should be at least 1.8 m, ideally 2.4 m.

- Top landing: Located at the top of the ramp, the landing allows ramp access across side flares, the width should be at least 1.8 m.

- Side flares: They prevent risks of tripping. The grade breaks should be at the bottom and the top of the ramp and be perpendicular to the direction of the ramp.

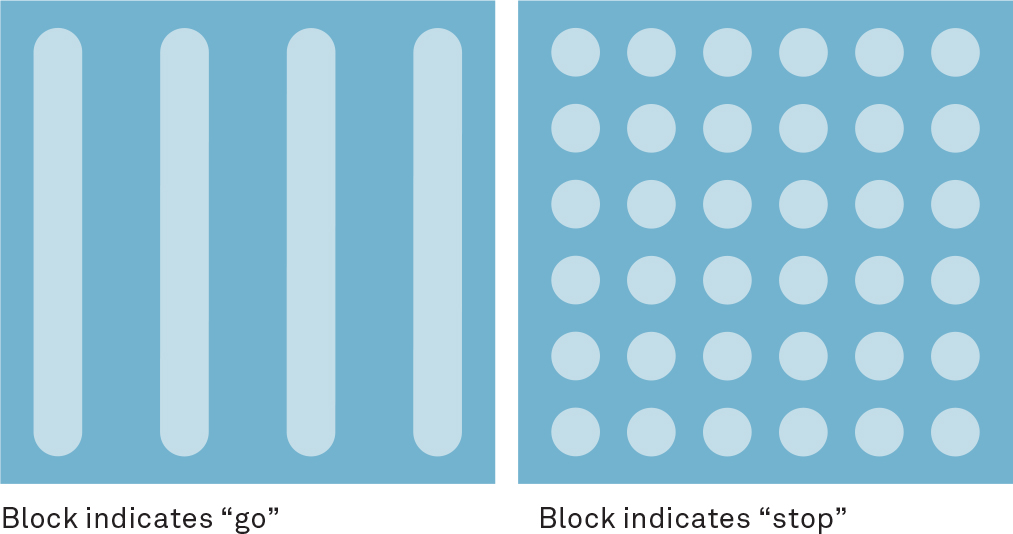

To alert people, especially visually impaired pedestrians, about the ramp or other potential hazards, pavements should include tactile paving:

e) Safety

Cities can easily get overwhelming for more vulnerable road users. Too many cars, too much noise, too much ‘chaos’. In this infrastructural web, it’s even more crucial to implement safety elements into the everyday lives of your city’s residents. See here for how to make your city safe for pedestrians.

f) Pollution

Walking next to loud and busy roads is no fun. According to Mário Alves, Secretary-General of the International Federation of Pedestrians, if cities are noisy and polluted, people don’t like to walk – furthermore, they start thinking they should buy a car and drive, consequently contributing to the problem. So how to make sure walking zones are comfortable for pedestrians? Avoid creating walking routes next to main roads, and keep things like lighting, benches, and providing shade in mind.

g) Scenery

Walking in an area with beautiful scenery is always a pleasure. It doesn’t have to be the perfect view of sandy beaches and golden sunsets, but walking zones should include fewer parking lots, garages, and grey buildings. Routes should be interesting, fun, colourful. Merely walking past a cute shop window can make a big difference. As Mário explains, people don’t necessarily like to walk, and if they walk without the distraction of a scenic route, they get tired faster.

Of course, the main point of walkable streets is to get from point A to B safe, quick, and stress-free. But streets should also be enjoyed, appealing to the eye, amusing, provide socialising possibilities and enhance economic development. Don’t plan walkable streets solely from the pragmatic point but add a human touch to it. Allow the street to serve as a travelling, social and commercial space for all road users.

Having said that, there are other purposes to frontage than mere amusement. Storefronts and windows of homes provide a sense of security, as there is almost a guarantee someone is looking out the window. Streetlights, positioning of buildings, trees and other architectural elements make sidewalks more appealing and safer, the weather-related aspect included as they can either provide shading on a hot sunny day or shelter from rain and winds on colder days. These buffers also help reduce noise and air pollution from motorised vehicles.

h) Efficient Parking

Keep in mind that not all road users will be able to switch to car-free for every trip they’re taking. There’s still a lot of room for improvement in parking management, though. If the city has an established and thought-out designated parking space provided for cars, drivers are less likely to park their vehicles on the pedestrian realm, where they take space away from pedestrians.

What to Consider – a Recap

There’s a lot to pay attention to when transforming infrastructure into a pedestrian-friendly one:

- Sidewalks should ideally consist of four zones and be accessible to all.

- Decide on the best type of pedestrian crossing, depending on the neighbourhood’s activity.

- Think about the functioning of traffic lights –putting them there is merely a start.

- Avoid direct road pollution and provide street safety with simple measures, such as providing street furniture and directing the route to colourful streets, passing interesting buildings.

- Provide parking for cars and create lively streets.

To better understand how to start implementing walkability in your city in the first place, read our ‘How to Get Started’ guide, as well as ‘The Challenge to Making Cities Walkable’ to get a grasp of the potential obstacles you might meet along the way.