Safe intersections are critical to any cycling city, yet are often the last link to be thought about. Here is a beginner’s overview to bike-friendly intersections, based on advice from three experts in the field.

Out in the Open: Why Bike-Friendly Intersections Are Important

There are two main reasons why any city trying to improve cycling needs to address intersections. Safety is the first concern. Over 70% of all lethal or serious cycle accidents happen at intersections, as this is where cyclists and motorists interact most.

“It’s the jungle law in traffic that you pay attention to the ones who can hurt you, but not the ones you can hurt,” says Troels Andersen, traffic planner for Odense city and the Cycling Embassy of Denmark. “Cyclists are therefore quite often overlooked and, by accident, get hit by cars.” Designing safer intersections for cyclists is therefore essential to reducing fatalities.

Secondly, intersections are important because they influence how people feel about cycling. “In many cities, the separated bike lanes or traffic calmed roads suddenly end when you reach an intersection,” notes Lucas Harms, Managing Director at the Dutch Cycling Embassy. “It leaves you out in the open, feeling very unsafe and vulnerable.”

This feeling puts people off cycling, particularly families and the elderly. “The reason that comfort is so important is because if people remember these near miss events, they stop biking” says Aaron Villere, Senior Programme Associate at America’s National Association of City Transportation Officials. Ensuring that intersections do not become a barrier to cycling is therefore vital for any city wanting to increase those riding a bike.

Guiding Principles: Visibility, Reduced Speed + Clarity

Once a city acknowledges that intersections are important, the next steps is to understand what the guiding principles should be when designing them.

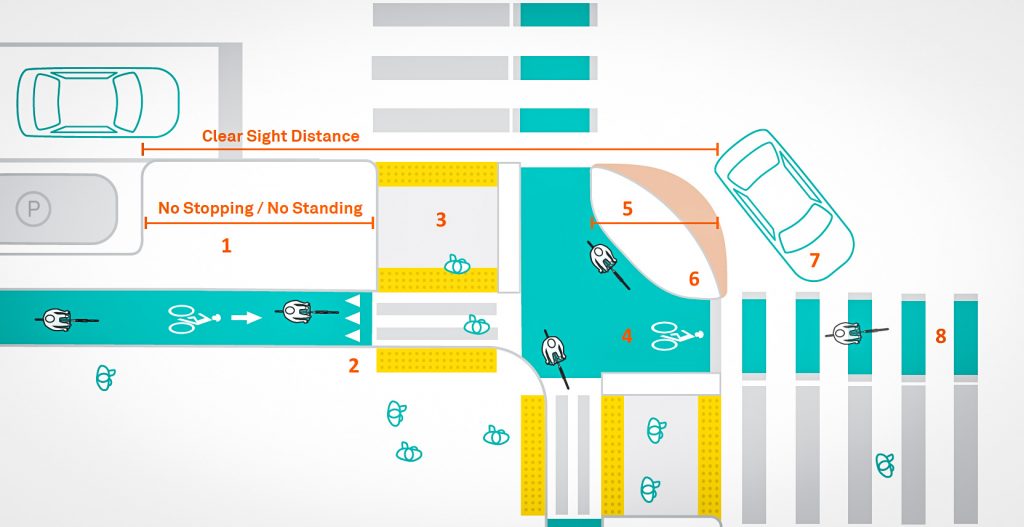

“One crucial element is that bikes are visible at the intersection,” states Lucas. This means that intersections should be planned to heighten the awareness of cyclists; bringing cyclists to the front of the traffic, having colour coded sections and ensuring that the angles of turns increase visibility are ways of achieving this.

Another guiding principle should be reduced speeds. “The faster people are turning through intersections, the more likely you’re going to have a conflict, and the more severe the conflict is going to be,” says Aaron. “So reducing vehicle speed is really at the crux of it, along with maximising visibility.”

A third principle commonly emphasised is self-explanatory intersections. If the intersection is unclear, then this will cause confusion and hesitation, which can increase the chances of collisions. An easily understood design is therefore crucial.

These three principles – visibility, reduced speed and clarity – should be the cornerstone for any bike-friendly intersection. By realising all three, it will help reduce fatalities at intersections and increase cycling comfort.

Intersection Designs: Which to Choose?

From the Dutch roundabout to the Danish left turn, there’s a huge range of intersection solutions and ideas which aim to increase cyclists’ safety. Many have overlapping concepts and some feature multiple names. Whilst intersection designs differ depending on the type of junction, the most common cycling intersections are the following:

- Protected intersection

- Dedicated intersection

- Right of way

- Dutch roundabout

- Phased Signal intersections

- Right turn on red

- Bike boxes

- Traffic islands

- Right turn shunts

- Grade separated crossings

- Two stage turn queue box

Determining which type of intersection to apply depends on a wide array of factors, from road speed to culture. We’ve outlined below some of the most important things to consider when deciding which intersection design.

1. Junction layout

The first determining factor will be the nature of the junction. Some intersections designs are only applicable to those with traffic lights (phased signalised intersections, protected intersections or bike boxes), whilst others can apply without traffic lights (Dutch roundabouts or traffic islands). Other designs focus on specific turns (right turn shunts, right turn on red) or T-junctions (right of way). The layout of the intersection will therefore significantly shape the design chosen.

2. Speed and Volume of Traffic

Where there are high speeds (>25mph) and heavy traffic volume, intersections which separate motor vehicles and cyclists are most commonly chosen. “If you’re turning right, and there’s a lot of vehicles behind you, you feel pressure as a motorists to clear the intersection quickly,” explains Aaron. This ‘back pressure’ increases the chances of collision, as drivers are incentivised to move quickly. Intersection designs which separate traffic, such as the protected intersection, dedicated intersection, phased signals or Dutch roundabout are therefore preferred at high speeds and volumes.

“If there’s not much traffic, our studies found that a lighter touch intersection works because vehicles aren’t feeling as pressured to get out of the traffic stream, so are more willing to yield,” Aaron states. “At really low speeds and low volumes, mixed traffic can work because you’re still getting visibility and clear interactions, and people aren’t coming from unexpected directions.”

Right of way solutions, mixed traffic or traffic islands may therefore be more appropriate at lower levels of speed and volume.

3. Space

The amount of space available will inevitably limit which intersection design can be implemented. A roundabout or protected intersection is simply not feasible at narrow crossroads.

That said, phased traffic lights can be a solution. “If you can’t separate people biking and motor vehicles in space, the other way you can do it is in time,” explains Aaron. By signalising for cyclists to move at separate times to motor vehicles, this provides the safety that would be afforded by physical separation.

As with all intersection solutions, however, there are certain drawbacks to this option. “The more phases you have, the longer waiting times, so the higher risk you have of people running the red light or of people getting tired of going by bike because it takes too long,” explains Troels. He nevertheless points to how the use of sensors to detect oncoming bicycles could alleviate some of that.

4. Range of Riders

Traffic planners should be mindful of range of people on bikes. “The design has to reflect the diversity of users and really listen to their voices,” Aaron urges. “People who are riding to work behave differently to weekend warriors or those riding with friends, family members or adaptive bikes. Intersections need to accommodate the whole universe of riders.”

Designs such as mixed traffic approaches or bike boxes may end up being exclusive or more vulnerable users who are wary of vehicles. Alongside considering the differing needs of riders, planners should also consider the expected number of cyclists at any given intersection. Traffic islands, for example, will have to be wider where a large number is anticipated.

5. Subjective and Objective Safety

When determining which cycling intersection to choose, cities need to be conscious of both subjective and objective safety. Feeling safe is not the same as being safe; even if a design is objectively safe, people will not cycle if it makes them feel unsafe.

“If people stop cycling because they feel insecure, then intersection solutions can become more unsafe as you lose the effect of safety in numbers,” warns Troels. “The more cyclists and car drivers get used to an intersection, the safer it becomes.”

Troels gives an example of how well-lit bicycles, with hi-vis clothing and bright coloured helmets would increase the visibility of riders at intersections; however, mandatory requirements would deter a lot of people from cycling. This may then reduce overall safety, as motorists are less accustomed to cyclists. Urban planners therefore face a balancing act between subjective and objective concerns.

6. Local Context

Local culture can also affect the intersection design chosen. Roundabouts, for instance, will be more popular in cities where they are commonly used. Allowing cyclists to turn on a red traffic light will work best in cities that strictly adhere to traffic light codes. Hence, some designs are better suited to cities than others.

The local traffic regulations will also impact which cycling intersections are possible. For instance, Aaron’s work with NACTO found that regulatory reluctance recognised new cycling intersection developments in certain states in America would inevitably curtail each city can implement.

Along with the other factors described, local context is therefore another significant influencer on the choice of intersection design.

In a Nutshell…

When it comes to creating a cycling city, intersections are the missing link. Not only are bike-friendly intersections crucial for safety, they are also a necessary piece to encourage people to cycle.

This overview has outlined the guiding principles, types and factors determining which intersection design is appropriate for building cycling connections. For more detailed information, we can highly recommend NACTO’s ‘Don’t Give Up at the Intersection’ guide and the Danish Cycling Embassy’s ‘Intersection Solutions’.