Micromobility has an image problem. In Paris, a mix of poor planning and bad user habits came to a head as the public voted for e-scooters to be banned. Mobility expert Dagmara Wrzesińska’s outspoken criticism of how the referendum was handled caught our attention – her explanation is a lesson for any city taking any controversial issue to public debate. She also offers suggestions for how we can better integrate e-scooters and other emerging micromobility into the fabric of everyday journeys – let us introduce you to MaaS: Mobility as a Service.

It seems no coincidence that in 2020 – the year that rentable e-scooters were introduced – car use in the Greater Paris region dropped for the first time. At their peak, the city’s 15,000 public e-scooters clocked 400,000 riders a month, most popular among young adults up to the age of 35 (71%).

That’s little consolation though, for the blow that was to come In April 2023.

In a referendum that sealed the fate of the e-scooters, Parisians sent an overwhelming message: 90% of those who turned out to vote wanted them gone. Although privately-owned e-scooters can still be used, a ban on public rentals came into effect on 01 September 2023.

It’s Not About Fun

The result of the referendum rolls back a lot of good work done during the COVID-19 pandemic. Paris authorised e-scooter rental services in response to social distancing policy, which had made it difficult for people to use conventional transport modes.

During this time, the popularity of e-scooters (and cycling) spiked. One service provider reports that they were used for essential trips such as grocery shopping and hospital visits. This flies in the face of some claims that e-scooters are mainly used as a novelty.

Dagmara Wrzesińska is a MaaS (Mobility as a Service) and urban mobility specialist. She saw first-hand how, especially during the pandemic, it was difficult to find an e-scooter not being used.

The majority of people are not taking the scooters because they want to look chic or whatever; they’re being used in peak hours as a regular means of transportation.

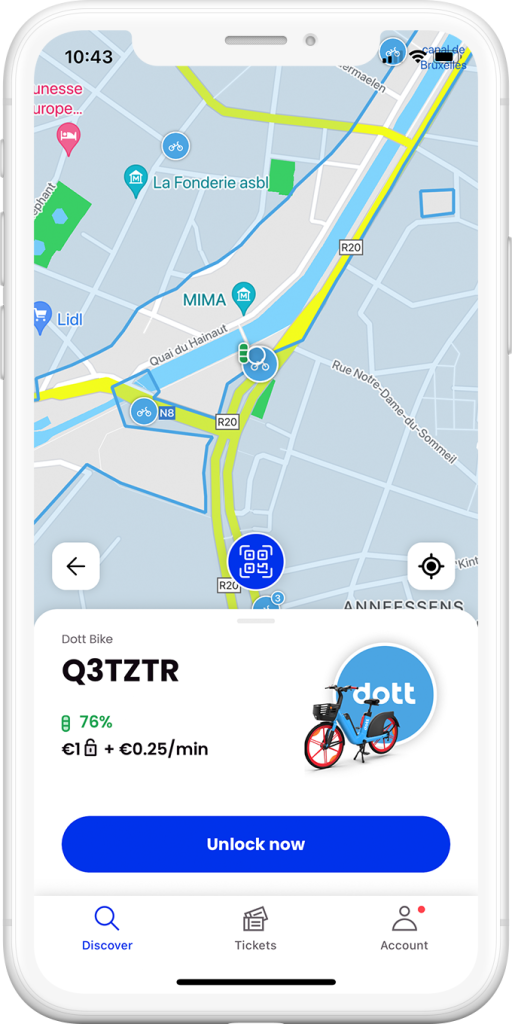

Located and activated via an app on smartphones, they could be easily picked up and deposited anywhere, making them more flexible than, say, buses and the metro. Plus, with no timetable, there is no waiting around.

As we push for car-free cities, e-scooters make sense. As short-term rentals, e-scooters are an affordable, low-carbon and a low-congestion alternative to cars. A study of the environmental impact in Germany, Belgium, and Portugal concludes that “an e-scooter emits 804 to 1679 g of CO2 per kilometer” with 70% of emissions created at point of production. Another source claims how 50% of average life cycle-sourced global warming impacts arise from raw material extraction and manufacturing, and as much as 43% expended on daily collection for charging. Riding them though makes few emissions.

Rumble in the Urban Jungle: The Clash of Mobility

Despite the advantages, e-scooters seem to have raised the ire of Parisians because of riders’ habits. It was common to see devices left blocking pavements (known as ‘scooter litter’), or people riding drunk, carelessly, or too fast, and even dumping them in the river.

Much of this, Dagmara points out, is a result of gaps in infrastructure.

“If there is not sufficient density in the parking zones, or these are very far from one another, it kills the point of the flexibility that the service offers.”

And if there’s no dedicated lane, as there often is for bikes, riders only have two choices: ride on the road or ride on the pavement.

It was a similar situation with cars in the early days. New rules – including designated parking spaces – were introduced in the very early twentieth-century to control the growing problem of vehicles being left blocking streets and pavements. User behaviour informed rules of the road and some believe that, rather than banning them, e-scooters should equally be given time to evolve their own infrastructure.

Behaviour Vs Design

These problems arise as many infrastructure issues often do, because of a lack of diversity: it’s generally non-disabled, full-time employed men who design our cities, and with cars in mind.

“If you never had the chance to take a baby stroller or a wheelchair, or if you never had a broken leg and had to move the crutches, you will never understand the struggle and take into account what a freaking terrible experience this is when you plan the infrastructure.”

Car is king and all other modes of transport are left to share the remaining space – or ‘street capital’. As new forms of micromobility come along, Dagmara says, they are forced to “cannibalise” from space that people already walk, roll, bike, hover, and skate on. Everyone feels their space being impinged on, which is what raised temperatures in the debate in Paris.

As surprising as it may be, this is as bad as it gets. E-scooters have low-level lighting and are mostly silent, but the risk of injury to pedestrians remains very low. In 2022, the rate of riders requiring medical treatment stood at just 4.1 per million kilometres, 20 times lower than for mopeds (interestingly, for comparison, in 2021, just 42 people per every billion car miles travelled were seriously injured or killed). But that wasn’t enough to save them at the ballot box.

When a Landslide Is Not a Landslide

Those who wanted e-scooters banned won the referendum, hands down. In reality, though, the 90% victory came from a turnout of less than 8%. Most people just didn’t bother to cast a vote.

Dagmara commends the use of democratic dialogue between citizens and the city, but explains how the Paris referendum was administered in a way that seems to have contributed to the low turnout:

- There was an obligation to pre-register to vote, even before the information campaign began, limiting participation.

- The electorate had to turn out in person – with no digital or proxy votes – excluding some people due to mobility challenges or for being away at the time.

- Only one polling station was opened in each of Paris’s districts, which led to lengthy queues, lasting hours and testing voters’ patience.

For those who didn’t care strongly enough, these were reasons enough to stay away, and the result has changed the mobility landscape of the city without us knowing whether this truly represents citizens’ views. Other cities too are finding it difficult to handle the pace of micromobility growth.

Cities That Offer Better News

Part of the problem is that EU member states have struggled to find a consensus on how to respond to e-scooters’ popularity. The Netherlands, Serbia, and Greece, for example, don’t allow e-scooters in public spaces at all, while in only a few countries – including Sweden and Finland – can they officially be driven on pavements.

Some municipalities are using lessons from Paris to embrace micromobility with a more systemic and regulated approach, boosting long-term feasibility.

Madrid has implemented strict rules, which are set to safeguard service operators, hand the city more control, and make the presence of mobility devices less problematic for citizens:

- Service providers are only allowed to supply 2,000 e-scooters each (although this may increase if there is a demand).

- There are limits to where the scooters can be ridden and parked.

- Users will continue to incur charges until the device is parked in an appropriate spot.

- Fines can be implemented for improper use.

- To improve safety, e-scooters cannot be taken on busses and the metro.

How Cities Are Responding

Italian citizens will soon need to have insurance. In Vienna, scooters are treated the same as mopeds, with riders required to wear helmets and stay off footpaths. The benefits of this have been verified by independent research, which found that mandating protective headgear and enforcing speed limits reduce chances of injury by almost half. Back in Brussels, e-scooters have been banned from pathways for more thoughtful reasons: to help elderly and partially sighted people feel more secure.

However, our CityChanger points out that the more cities impose restrictions on service providers, the more their business models are put at jeopardy and the less sustainable they can be.

As it is, operators get a lot of direct criticism for incidents that the motor industry wouldn’t be held responsible for – driving a car drunk is a police matter, so why should e-scooter providers be held accountable when riders are under the influence? This hints at an imbalance that surely influenced the result in Paris.

Creating a Cohesive Urban Transport Network

Because they are still fairly new, we are still trying to define our relationship with e-scooters as a viable transport option.

Reaching what Dagmara calls the “gold compromise” – a system that works for the public, operators, and cities – is not easy to accomplish. It relies on three components:

- service providers and authorities engaging in open dialogue and being willing to cooperate.

- a change in public perception of micromobility to bring it in line with more traditional transport.

- experts to support stakeholders to adapt.

It requires political courage and thought leadership, because these are not easy discussions.

MaaStering Micromobility

Having trained as a transport engineer, Dagmara went on to work for the National Road Safety Institute in Belgium, micromobility provider TIER, and later the POLIS network. She’s now with Trafi, a MaaS (Mobility as a Service) platform provider that originated in Lithuania.

This rich knowledge base has equipped her with a rounded view on what sustainable and user-focused urban mobility can look like, and she believes that MaaS can help.

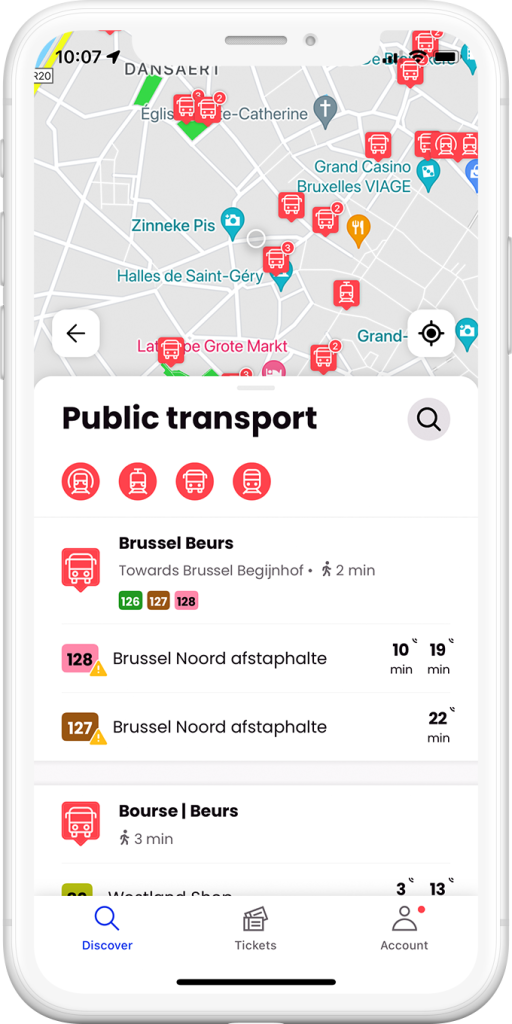

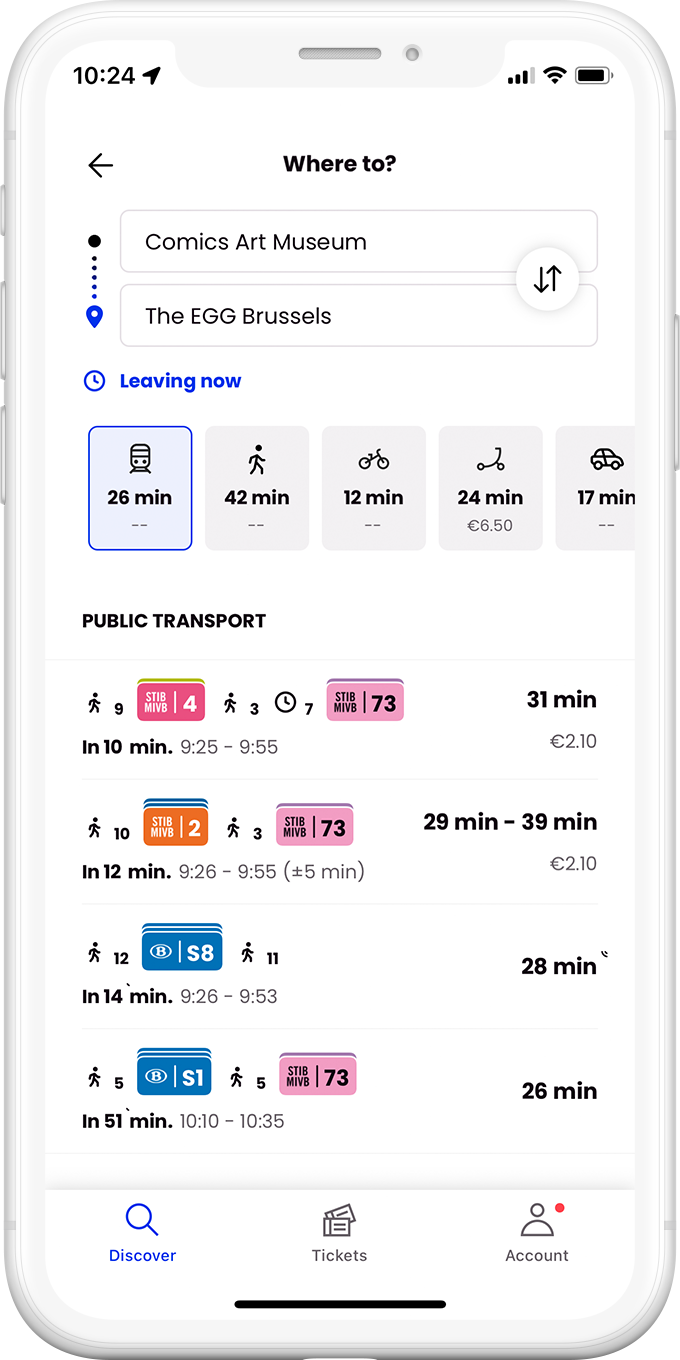

MaaS is the name given to a fully integrated, diverse, coordinated, and optimised transport network with a single easy-to-use interface, all of which responds to diverse user needs.

“The MaaS concept is an end-to-end experience for a user for a given journey,” our CityChanger explains. “So, you need just one account. You register once, and you have access to all of the mobility providers in the area, from route planning, booking, paying, validating the trip, and accessing help, if necessary.”

Showing the quickest, shortest, most cost-effective or carbon-neutral route from A to B at the touch of a button requires calculating all the options and presenting them in real time, accounting for traffic jams and delays. It should show the best personal route by combining all relevant mobility in a single journey, from trams and trains to buses and hire bikes. MaaS also encompasses options for soft- and micromobility too, and – maybe surprisingly – cars.

We cannot drive society in the direction that everyone is obliged to follow one certain paradigm of how they should be moving.

Cars as Part of MaaS

As a realist, Dagmara advocates to stop the competitive narrative in favour of better incorporating car usage to optimise MaaS solutions for a greater good.

Sharing services can contribute to reduced car ownership – but it is challenging to offer the same level of comfort that a private car does. Nevertheless, and as much as certain car trips will not be replaced with alternative modes, some of them certainly can be.

By combining services, MaaS has the potential to normalise micromobility and help emerging modes like e-scooters be seen more positively.

Simplifying Access for All

For MaaS to be put in place, cities need experts like Dagmara to guide them through the process. She works with cities to develop the tools they need to launch and operate a MaaS system without the need for extensive internal expertise.

There are plenty of independent operators but putting MaaS in the hands of cities is a logical step.

MaaS started out in the B2C (business-to-customer) sector but over time has migrated to a B2G (business-to-government) model. Cities are better placed to bring together the various actors needed to coordinate a city-wide transport network.

It’s a big commitment for cash-strapped European cities but attractive to municipalities with sustainability targets and public health policies that promote active mobility. Most recently, Dagmara’s colleagues at Trafi launched Brussels’ Floya MaaS portal in line with the city’s Good Move mobility plan.

Of course, all this relies on one thing: users having devices capable of accessing MaaS platforms. Germany and the USA are rare in that their smartphone penetration (ownership) rate is above 80%. Even in the best-case scenario, that leaves one-fifth of the most connected country unable to make use of the services. Dagmara admits this is a problem yet to be solved. Still, it’s clear that setbacks like this don’t eclipse the advantages.

Next Steps: Incentivising Behaviour Change

Just because Paris voted to eliminate a single form of mobility doesn’t cast out its sustainable city status.

Since 1990, journeys by public transport have increased by 30%. This wasn’t the result of a public vote. Sometimes nudging and gradual change is a better option than straight democracy.

Dagmara would like to see governments incentivise change. One way she suggests is by ending the tax relief on private and fossil-fuelled transport like company cars. Instead, she says, tax-free allowances could be offered for using sustainable mobility: bus and metro tickets, EVs costed by the mile, bike and scooter hire, etc.

Coupled with MaaS, this would be cheaper and more convenient. After all, our CityChanger notes, it’s not the price of public transport that prevents people using it, but a question of reliability.

So, cities can also leverage MaaS as a platform for positive messaging. Normalising and promoting the flexible, affordable nature of e-scooters could change their fortune.

We can talk about micromobility in terms of independent travel – which makes the car so popular – while at the same time label it as climate conscious and less subjected to traffic congestion, delays, and cancellations.

Implemented earlier, this approach may have prevented the politically charged systemic failings seen in Paris. We cannot know that for sure – but what we do know from this experience is how not to run a referendum.