São Paulo is a tale of two cities. A broken relationship with water has created a litany of challenges, which hit the sprawling favelas harder than the wealthy centre. The Secretary of Urbanism is showing how intelligent and integrated plans for water-sensitive cities can shift inequities in water supply, sanitation, and safety – but also how attitude may be harder to change than the built environment.

Paulo’s Drainage Problem

Brazil’s basins hold about 12% of the earth’s freshwater supply – the largest proportion of any country. Even so, it is unevenly distributed, with larger cities facing water stress due to huge populations.

To make matters worse, in 2014, São Paulo encountered drought conditions.

Pedro Fernandes is quick to point out that it was a freak occurrence: “We don’t have huge problems with that compared with other cities in the world.”

In fact, too much water is generally the issue here. São Paulo experiences dry winters but very wet summers – up to 120 millimetres per day.

With such volumes, deforestation has increased the chances of flooding and soil erosion has led to the silting up of reservoirs, reducing storage capacity, affected potable water supply and hydroelectric generation.

The São Paulo Water Fund has attempted to restore forests in the surrounding region in order to manage these issues but, as the city sits in the bowl of the Tietê water basin, a lot of the rainfall ends up in the metropolitan area, which houses 21 million people.

“We don’t have appropriate infrastructure there to retain the water”.

There’s a knock-on effect. Lying low at just 750m above sea level, the city has a drainage problem, which the municipality – specifically the Secretary of Urban Infrastructure and Works and the Secretary of Urbanism and Licencing – is trying to fix.

Pedro Fernandes, the department’s technical advisor in the Secretary of Urbanism and Licencing, coordinates ways of using urban infrastructure to “redraw the city and to rebuild and bring transformation and [create public] spaces” that improve São Paulo’s relationship with water.

Adding to this challenge is the city’s stark class divide, where very different issues face either end of the socio-economic spectrum.

Privilege Presents Problems

Rivers pass freely through some of São Paulo’s richest districts, including the most affluent Pinheiros neighbourhood. Even here, waterways openly carry sewage.

Sanitation has fallen foul, especially, of the separation between city and state.

The 18 municipalities that make up the metropolitan area are each responsible for stormwater and waste management in their jurisdiction, while water supply and sewage are concerns for central governance. This disjoint perpetuates pollution. A lack in coordination between the Secretaries of Urban Development, Infrastructure, and Environment has further held back progress in integrated water management.

“If you don’t have a proper [integrated] system, the waste goes into the rivers in the end.”

What’s more, construction of roads and industrial development have decimated any sign of the natural world and much of the city’s indigenous heritage.

Instead of grieving these losses, São Paulo’s wealthier inner-city dwellers – typically a conservative crowd – are protective of their car culture. Existing infrastructure prioritises independent motorised travel and any suggestion of change is seen an infringement on residents’ rights and freedoms.

Struggling Inner City Solutions

Pedro emphasises the need for a shift in attitude.

“We want to change people’s view; how they can see the water as a place for leisure, for sports, or enjoy being in front of,” this CityChanger tells us. This is being attempted with a very practical solution: blue-green infrastructure.

The Secretary of Urbanism is creating the large Parque Dom Pedro II along the River Tamanduateí. This will see São Paulo’s largest bus terminal replaced by a pedestrian-friendly promenade in line with the Strategic Master Plan, which outlines linear parks as a mechanism to revitalise the local economy, multi-mobility, and environment.

However, changing residents’ mentality, and the culture that perpetuates it, has struggled to take hold. “We still have bad [water management] projects because we are very divided. We are still designing projects which are very car oriented,” Pedro admits.

The neighbourhood of Ipiranga is an example of what can go wrong. To solve the drainage problem, a reservoir was introduced to aid retention, but the road system expanded alongside it, placing a barrier between people and the water. The bond remains severed.

Viva Favelas – Informal Housing & the Lack of Water Justice

The issues faced by São Paulo’s informal settlements differ vastly from those of the centre.

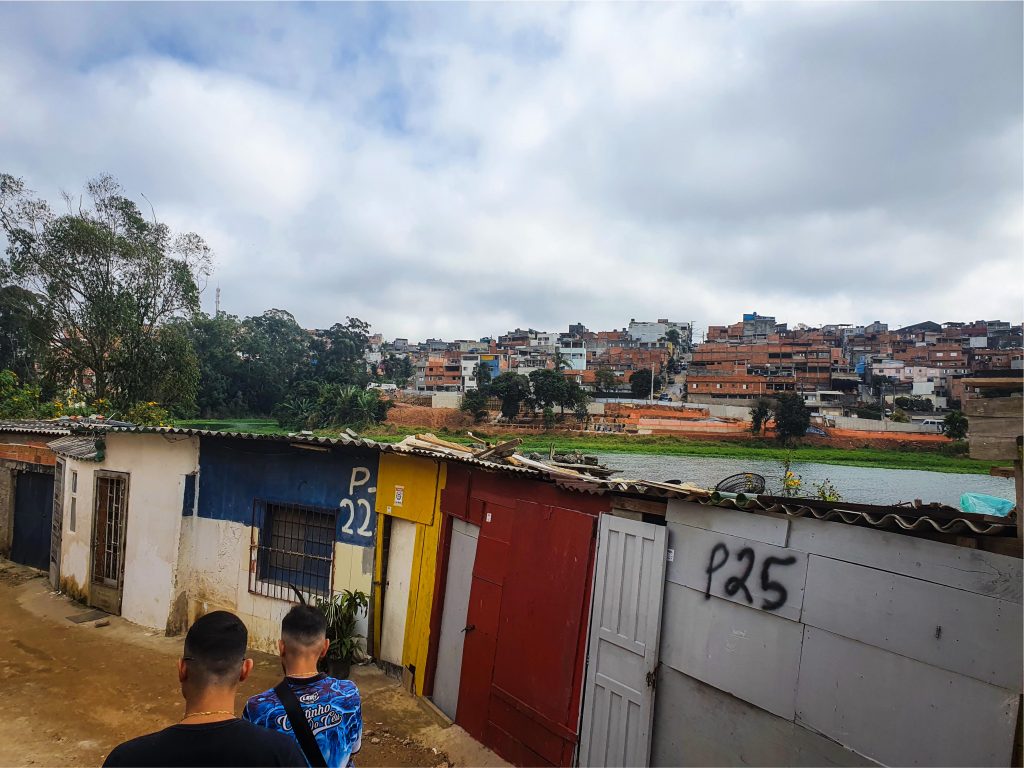

On the outskirts of the city, residents build dense dwellings close to the water’s edge, outside of planning regulations. The infamous favelas are home to 800,000 São Paulo residents. It’s common for those who live on the edge of the reservoirs to lose everything they have to rising water or subsidence.

The 15 per cent of the city’s population which lacks access to proper sanitation is concentrated largely in these sprawling communities, too, which have almost no piped water and no underground sewage systems.

Here, waste continues to run into natural waterways, polluting the natural streams and aquifers that drain into local reservoirs, an important source of drinking water. With wealthier citizens able to afford bottled water, this disproportionately infringes on São Paulo’s poorest citizens the most.

Relocating Residents for Safety

Pedro states, with some urgency, that water issues in the favelas are inseparable from the subject of housing.

A UN Habitat report makes it clear that the favelas are built on floodplains and hillsides. Runoff frequently engulfs buildings and endangers life.

The municipality – while sympathetic to citizens’ requests for improved water supply and sanitation – has a duty to prevent illegal land use.

With little choice, São Paulo has taken the drastic step of removing favela residents from the water’s edge and relocating them in social housing projects, shattering their social, family, and economic networks.

“We have to do that, because otherwise we destroy the whole environment,” Pedro tells us.

In place of the removed slum dwellings, managed waterfronts like Parque Linear Cantinho do Céu are being introduced.

These stabilise drainage and flood control with nature-based retention and filtration and improve the quality of life for those remaining.

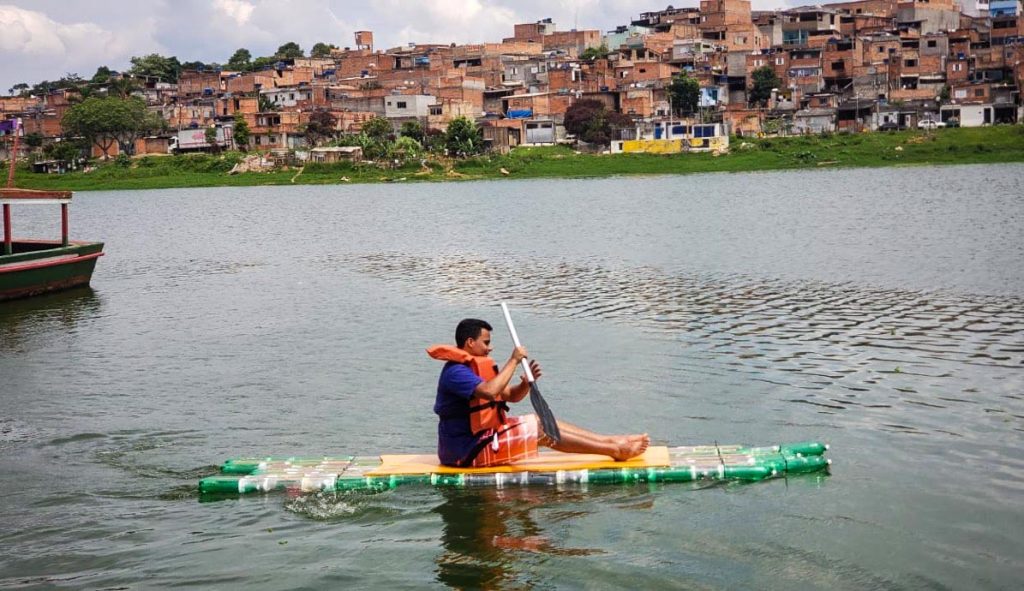

Including space and structure in the design for public transportation and water-based tourism is intended to attract the tourist dollar and state investment, as happened in Colombia’s favelas. Theoretically, this could see infrastructure improve over the coming years.

“We already see a lot of benefits,” Pedro points out, “more people walking, more people going outside, more people staying together in that space. We see the environmental education and the social movements are getting more involved.”

Lessons in Water & Reuse

Forming a tangible, personal connection with water underlies São Paulo’s strategy as a water-ready city, and the concepts practiced in these two distinct locations are blueprints to be rolled out elsewhere.

Criticism is hurled at municipalities for investing in these projects while housing is still lacking, but Pedro notes, “We have to invest in every sector at the same time”. São Paulo’s future as a water resilient city depends on it.

He also hails the entire experience as a pedagogical opportunity, a chance to educate São Paulo’s population about water treatment processes and the importance of circular concepts.

Some 23 kilometres south of the city centre, the Secretary of Transport and Mobility – advised by The University of São Paulo’s Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism (FAU-USP) – is constructing two new ports on Billings reservoir. It’s a body of water that has been extremely polluted since the 1980s but there are now proposals in the municipality for using the water from there to clean the streets and distribute to local industries.

It was an easy sell. The commercial sector has grown uneasy over the reliance on water networks with the looming threat of drought. For many companies, this has been an incentive to invest in water capture and recycling, bringing commercial stakeholders in on solutions that support the city.

The push to clean, store, and repurpose sewage and polluted rain runoff for domestic use, too, in the drier winter months could prove to be essential to avoiding a ‘Day Zero’ scenario.