Urban development isn’t always about the brand spanking new. It’s all well and good to build new modern constructions, but it’s even more essential to give those run-down, if not abandoned areas some love and attention and use what we’ve already got. Caren Ohrhallinger, Chief Executive of Architecture at nonconform told us all there is to know about the importance of revitalising abandoned districts, the Doughnut vs Krapfen Effect, and how to go about bringing a city back to life.

Everybody likes doughnuts, and the German-speaking world so much so that they have a word specifically for filled doughnuts: Krapfen. You know the ones, whether it’s strawberry or apricot jam, vanilla custard, or chocolate, it’s a doughnut filled with yumminess that oozes out and stains your t-shirt upon first bite.

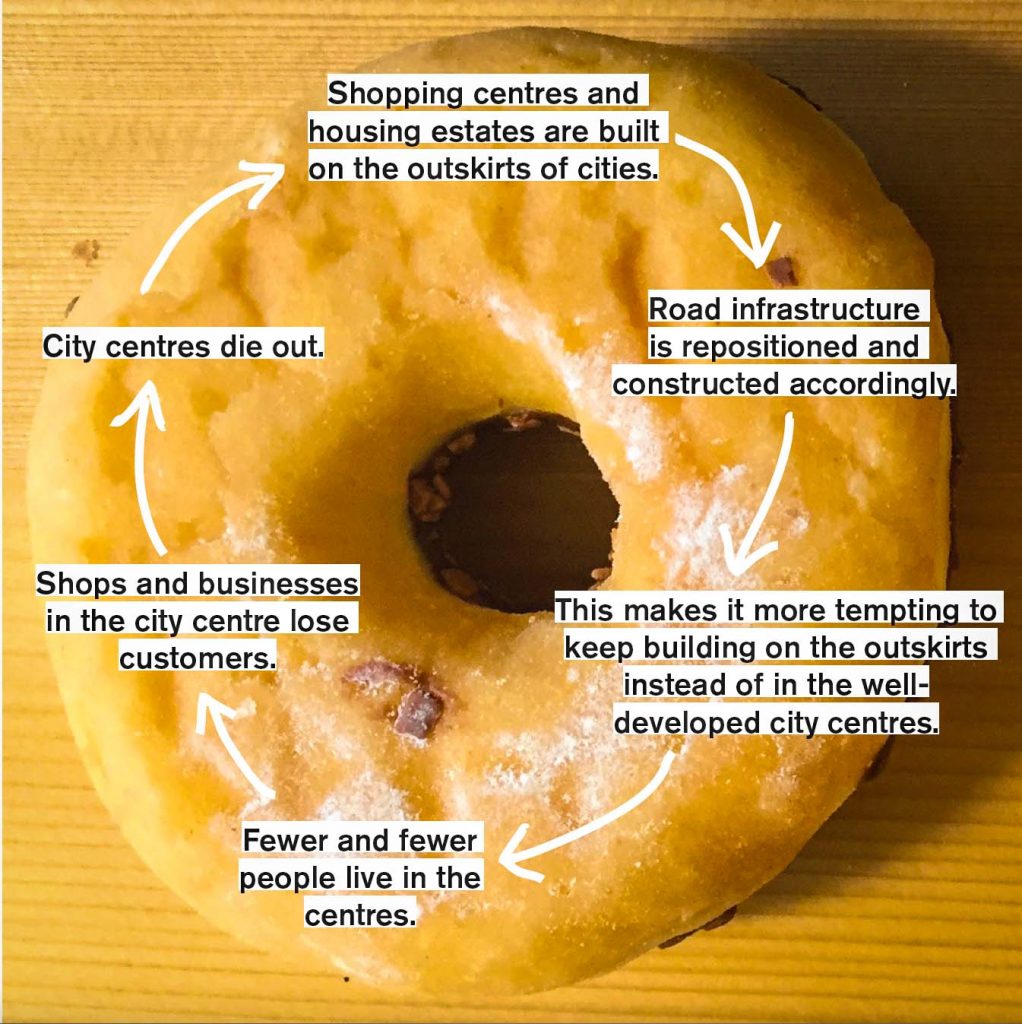

What have doughnuts got to do with urban development and revitalising cities? Well, according to Caren Ohrhallinger, quite a lot. In fact, she explains, it is a metaphor that has been coined by Hilde Schörteler von Brandt (Donut-Effekt) and Roland Gruber (Krapfen-Effekt). It depicts the sustainable and slightly less sustainable ways our cities can develop, and why it is important to turn our urban spaces into Krapfen, not into doughnuts.

What Is the Doughnut vs Krapfen Effect?

Let’s make this clear: when we say doughnut, we mean a Simpson’s-style ring doughnut; when we say Krapfen, we mean a messy doughnut with a filling. And these are essentially the two ways we can develop our cities. Regarding towns and cities, Caren says, “They can either continue expanding outwards with city centres becoming increasingly empty, giving you a doughnut”, or we can incorporate the development of city centres into urban planning, giving you a Krapfen. So, ideally, we want to be turning our cities into Krapfen. This is where revitalisation comes in: the idea of turning abandoned, empty, or unused places into somewhere that is new, enticing, engaging, and functional. It is about creating contemporary and creative living, working, business and leisure spaces which make use of the space we’ve already got. This essentially answers the question of why it is important to revitalise city and town centres.

What’s the Problem with Doughnuts?

Let’s take a look at the main reasons we should be focusing more on filling our doughnut and our city centres.

1. Infrastructure and Mobility

The first issue Caren mentions is that of mobility: “It’s not only about the streets and the infrastructure you’ve got to build, but more about things like where and how far the kindergarten bus has got to drive”. The further out of the city centre people live or infrastructure, such as schools, kindergartens and shops, is built, the further citizens have to travel in order to do, well, anything. (If you’re curious to read up upon the inequality between suburbs and the centre of cities, check out our interview with Gia Chinchilla.)

While this is time-consuming and inconvenient for the average citizen, she goes on to say that another, perhaps more prominent issue is that of mobility for those who are no longer mobile. If local amenities (e.g., supermarkets) are not centrally located and within walking distance, and you don’t own a car or can no longer drive, then you are reliant on either the public transport network or friends and family. Caren explains that “as a municipality, you’ll have to put in a lot more effort and create the transport infrastructure to make up for it” – “it” being the hole in the centre of the city, the poor infrastructure layout, and lack of interconnectedness. ‘Forced mobility’ is a consequence of doughnut-style urban areas. It’s the idea that people will be forced into being mobile (i.e., having to take the car or public transport) to reach the most essential services.

“It is about proximity and walking/cycling accessibility, and this can generally only be guaranteed if there is a certain density of residents. You tend to have this in a more dense, built-up centre than in a housing estate”.

While there probably are some automobile fanatics out there who jump at every opportunity to get behind the wheel, most people drive because it’s convenient and saves time. But “where there’s no alternative, if you want to reach the basic infrastructure, then it’s something you’ve got to do”, Caren tells us.

Of course, the extent of forced mobility varies from place to place, depending on how the environment and the infrastructure are knitted together. However, our expert makes it clear that “doughnut locations = forced mobility” – this is almost a foregone conclusion. And not only that, but there are also the “increased motorised transport, CO2 emissions, and land consumption” that are associated with it.

2. Land Use

Nicely linked to the issue of mobility and infrastructure is the fact that doughnut cities use land in a pretty inefficient and unsustainable way. Caren sums up her exasperation with this situation, saying, “it is crazy, how much [land and resources] we are still consuming daily, and the majority isn’t even housing”.

She elaborates that if we build supermarkets, shopping centres, etc., on the outskirts of cities, not only do they consume a vast amount of space, but you then also need the land and resources to provide access. It’s worth bearing in mind that it’s not just a supermarket building; you also need storage space, a car park, delivery area, etc. If built in, or close to, the city centre, often these amenities can be shared by multiple individual infrastructure arms. And then there’s the added bonus of needing to cater for forced mobility less because more infrastructure is within walking distance.

But it’s not just the where that is significant. Caren also highlights that cities should be looking at how housing is being constructed: “It makes a big difference, whether we build detached houses or build densely.” That doesn’t mean we all have to be living on top of one another. We just need to be savvy about it. Therefore, avoiding “constantly dedicating pieces of land in a municipality in a haphazard fashion like a patchwork quilt and building individual houses and estates” is a good starting point.

We need to be building up the city and not building in individual housing estates. The anonymous, one-purpose estates and blocks have run their course and are not a feasible model for the future. This is a wasteful use of land that is not feasible long-term, particularly with urban environments growing by the minute: 70% of the world’s population is expected to live in urban areas by 2050. It’s about creating future-proof living spaces that enable a balanced mix of shops, bars, offices, and apartments to be constructed together, even in one building, so that it offers a multitude of uses. It’s about putting the general durability of properties back at the centre of our thinking. To do so, we need to create architectural and spatial structures which we can develop and adapt. And because they can adapt to changing environments and demands, in the long-term, buildings that are flexible and open to different usages are more economical.

3. Social Hubs

It’s safe to say that many people, particularly youngsters, move to or like living in city centres for the social life. They want to be in the heat of the action. But if doughnut locations become more of a reality, this may no longer be an option.

Urban centres are traditionally hubs of social activity; points of both planned and chance encounters, due to the density of people. And why is that? Well, because all the infrastructure and amenities are in one place.

Of course, in doughnut locations “other places emerge; places that feel like centres and meeting points. For example, the supermarket carpark or the petrol station… but how sad is it, that this is what it has come to?”, says Caren. Rather than it being a nice town square, a local coffee shop, the newsagent, or manicured park, if people want social interactions, they have to travel to the edges of the municipality to find it. And there, it is likely only found at the larger-scale locations. Not exactly the easiest nor the most aesthetically pleasing place for a sociable catch up.

There are two additional issues associated with this, Caren tells us: “It excludes a lot of people who aren’t mobile, and on the other hand it forces people to be mobilised”.

“So, if we don’t want that, then we need to ensure that we keep the city centres alive, or we revive them”.

Turning Doughnuts into Krapfens: How to Revitalise

It’s all very well knowing why we should be trying to bring our city and town centres back to life, but the question is how? Caren offered us three case studies of projects in Austria that nonconform has worked on and all display best practices for revitalisation.

1. Leoben, Styria

At first, Caren’s description of Leoben makes it sound like an attractive, well-functioning town: “The main square functions really well; it is buzzing and super busy.” They also have an inner-city shopping centre which Caren describes as “a real magnet”. And then comes the ‘but’: “Two streets further on there is a huge amount of abandoned property.” This scenario probably sounds familiar to many CityChangers.

Reality Check

The main take-away from Leoben, Caren explains, is taking that very first step of “realising we’re at a turning point which will either follow a downwards or an upwards spiral”. It’s about recognising that the next decision the municipality makes will impact the future of the city in immeasurable ways and it’s time to start really thinking about what they want and what they need to do next. She says, in Leoben “they’ve recognised it and they are doing something about it”. Those empty shop fronts can’t and won’t stay empty forever.

2. Kardinalviertel, Klagenfurt, Carinthia

What can we learn from here? There are actually multiple tips and tricks from the Kardinalviertel. First up, just get up and do it.

“Take Action and Raise Awareness”

In the Kardinalviertel, nonconform worked with real estate owners to address and overcome an attitude that gradually became ingrained in the local mindset over the years.

There are two large buildings here in important locations. The widely held belief among the property owners was that if they couldn’t do anything with these two giants, then they couldn’t do anything to revitalise the town at all. This left the area and the buildings empty and abandoned for a long period. Caren clarifies, “it was important that something finally be reinstalled there, but it went round in circles”.

Eventually they hit a crunch point, and something started happening. They appointed a caretaker, which Caren describes as someone to look after the process and act as a communication facilitator and “an information interface between the people, the municipality, and the property owners or owners of empty buildings”. And once the ball is rolling, “gradually other things occur too: people settle down there, and beam and rave about the positive things” just because something is happening.

Work With What You’ve Got

Linked to this Caren tells us that “it is important to work with what you’ve got”. There’s no point sitting and sulking and waiting for something to change. Accept the situation: why work against it when you can work with it?

For instance, just choosing the area (e.g., a street or square) and doing something there. It could be something as simple as an outdoor cinema evening. Our expert elaborates that this is “a great use of space and it doesn’t require any designing. You could just say ‘bring your own chair’ and that works”. It doesn’t have to be fancy; it’s just about drawing attention to the place that you want to revitalise. Once there is something going on, once there are people ‘inhabiting’ the space, even if it is only temporary, the next steps of revitalisation will start falling into place.

Sharing Is Caring

More specifically, says Caren, “it’s all about sharing information: how it works and how it went for me. Then others can profit from it, too”. This is an essential resource that is often overlooked. We can learn so much just by interacting with others and listening to their experiences. Knowledge sharing can be just as good as sharing the real doughnuts!

In the Kardinalviertel, part of the development came in the form of one person saying they were having trouble renting out apartments because they didn’t come with a parking space. Through some networking efforts, another person revealed how they had managed to rent out similar living spaces by offering them to students. Caren sheds some light on this: “Someone said that they often offer these apartments to student living bubbles because, for the most part, they don’t own a car anyway.”

Networking

Another nugget of advice from our expert is to “create the connections and bring people together”. Here she specifically mentions the owners of properties of empty buildings. Sometimes you will find those who have been renting out this property for decades and still trying to do so at the same rate or under the same conditions as before. But, of course, things have changed, and this seldom works. Alternatively, there may be proprietors who are not living in the city themselves (or do, but don’t care) and are therefore unaware of the magnitude of the issue.

In this respect, it may be time to focus on raising awareness. Caren tells us that quite often, the owners of buildings are unaware of depreciating effect having an abandoned building can have on the surrounding area. They may just require a wakeup call and to be shown how and why they need to take responsibility for this.

Naturally, there will be those owners who do want to make a difference but don’t know how: “Oftentimes they are desperate, saying ‘no-one wants to rent this or that ground floor, what should I do?’”, Caren explains. There really are a lot of questions and it can be a nerve-wracking, precarious situation and a risk for landlords to try something out, especially if they have no previous experience. They may be concerned about how it all works, what they need to watch out for. Is it even possible, and what happens if it goes wrong? According to Caren, this is where “an abandoned property platform” could come in handy, “so that individuals searching for somewhere can find all of the information in one place and perhaps even contacts too”.

Among other areas of importance, nonconform achieved this give-and-take arena for sharing information through their Leerstandskonferenz – Abandoned Property Conference. This is an arena for knowledge sharing. The first of these was in 2011 and there have been seven more since. Caren proudly states that each conference has an overarching theme. For example, in 2018/19 it was brownfield sites, and the topic in 2022 will be “Nobody Home – The (Half) Empty House”. The main aims of the conference are to:

- connect the people associated with the issue,

- showing best practices,

- “give the municipalities, the communities and the people who are suffering from the effects of abandoned property the possibility for exchanges and to absorb examples and inspiration”.

3. Fließ, Tirol

It wasn’t always the picturesque Austrian village that might remind you of the Sound of Music, but with the help of the residents themselves, two brilliant architects and nonconform’s idea workshop, Fließ managed to turn things around. The municipality of Fließ is a classic mountain village of 3,000 inhabitants set in the middle of the Tyrolean alpine landscape near the district capital of Landeck in Tirol.

Participation Creating a Krapfen out of a Doughnut

On a large pocket of land in the centre of the village where multiple abandoned buildings stood unused for several years, there now stands an exemplary, multi-functional village centre with living, working, recreational and shopping spaces. In addition, a new village square was erected which acts as a social meeting point.

The whole project emerged with the help of intensive participation from Fließ’s population. Here, local knowledge of citizens was combined with the external expertise regarding a sustainable upgrade of the village centre with a helping hand from one of nonconform’s idea workshops. For this pilot project, which began in 2013, the dialogue between the municipality, its’ citizens and the architects took the form of a new model of architectural competition which emphasised acute involvement of citizens. From this a high-quality implementation project was developed, one that was accepted by all citizens and contemporary at the same time. It was planned by the renowned architects Köberl & Kröss and was completed in 2015. It has already won multiple prizes. What made this project stand out, was that it took very little to convince the residents why the project was chosen. Usually, it takes time and a lot more effort to win over the citizens once they have been involved in the competition process.

This project provides a decisive, lasting impetus to make the town center more attractive and guarantees that it will become the center of life again. It is a multi-functional development across several levels which has brought and will continue to bring a sustainable, future-proof way of life to the village. You can find out more details here.

4. Wolkerdorf, Lower Austria

Do It Yourself

While extensive design, revitalisation, and construction projects are great, we know that this isn’t always a possibility. Maybe you, as a municipality, aren’t 100% sure on what you want to do to bring public space to life. And, of course, there’s always the inevitable question of how to finance such actions. This is where a spot of DIY comes in.

“It’s about showing citizens the possibilities, so they are moved to act; it’s about enabling and empowering them to design their own living space, giving them the opportunity and them not having to wait for anything.”

For citizens, this can be waiting for the municipality to make a decision or make money available. For the authorities, they often have to wait to receive funding and permission from the county or region. So, let’s forget the grand designs.

Caren advises that “it’s more about the small things that you can bring into the current budget and can do yourself”. For instance, to help add life to the school district in Wolkerdorf, nonconform advised taking some big pot plants, temporary furniture made from wooden pallets, and collaborating with the school to create temporary installations. All of these are easy, cheap, and readily available; it requires little effort or input from the municipality. Exactly the formula you need for bring some life to public spaces.

Revitalisation in a (Dough)Nutshell

3 steps to success:

- Internal Development before External Development: the top priority is for politics to commit to the motto “internal before external development”. This means concentrating on strengthening the town centre and the potential for re-densification of existing buildings. Equally, it requires a clear rejection of the urban sprawl of the suburbs which would promote the doughnut effect.

- Innovative Public Participation: using courageous participatory processes to motivate citizens to think and develop a multitude of ideas together. This is a decisive step towards creating a comprehensive space that will ultimately make the whole community feel at home.

- Installation of a Caretaker: it has been proven that for successful revitalisation of centres, a so-called caretaker will be needed. This is someone who ensures that the project envisaged in the master plan is implemented according to the requirements and in a timely manner. Find out more about the caretaker here.

So, CityChangers, you now know why it’s important and there are a few ideas to get you started. What are you waiting for? If we want to make our towns and cities as sustainable as possible, and to create urban environments that people actually want to spend time in, it doesn’t mean you’ve got to start afresh. Take a look at what’s under your nose and bring it back to life.