Have you noticed the extremely high temperatures this summer? Especially when walking around a larger city? That is because city concrete and rooftop tar contribute to temperature increase and creating what is today known as the Heat Island Effect. What does it mean for the future of city living? And is there a way to reduce it?

We spoke with Paul van Roosmalen, Programme Manager of Multifunctional Roofs at the Municipality of Rotterdam, about the role roofs and grey surfaces play in the reduction of the heat island effect. Can they really make a difference? Are they the tool needed to fight climate change? Let’s find out.

Heat Island Effect: Everything You Need to Know

Why It Occurs

The urban heat island effect means the air in the city is hotter and drier than in the surrounding area. Urbanisation and interference in the natural landscape are the main culprits of its development.

Varieties

Mainly, we differentiate between two types of heat islands:

- Surface Heat Islands: created by higher absorption and emission of heat from urban surfaces (e.g. rooftops, pavements).

- Atmospheric Heat Islands: created by the difference of temperature fluctuations between urban areas and surrounding outlying areas.

Change in Temperatures

The temperatures in the city rise especially during the summer, due to the heat-absorbing tar and dark roofing materials. In fact, a black roof reflects 5% of the sun’s energy and emits more than 90% of the heat it absorbs, and a metal roof reflects 60% of the sun’s energy and emits 25% of the heat, meaning such roofs on a hot summer’s day can reach up to 82°C.

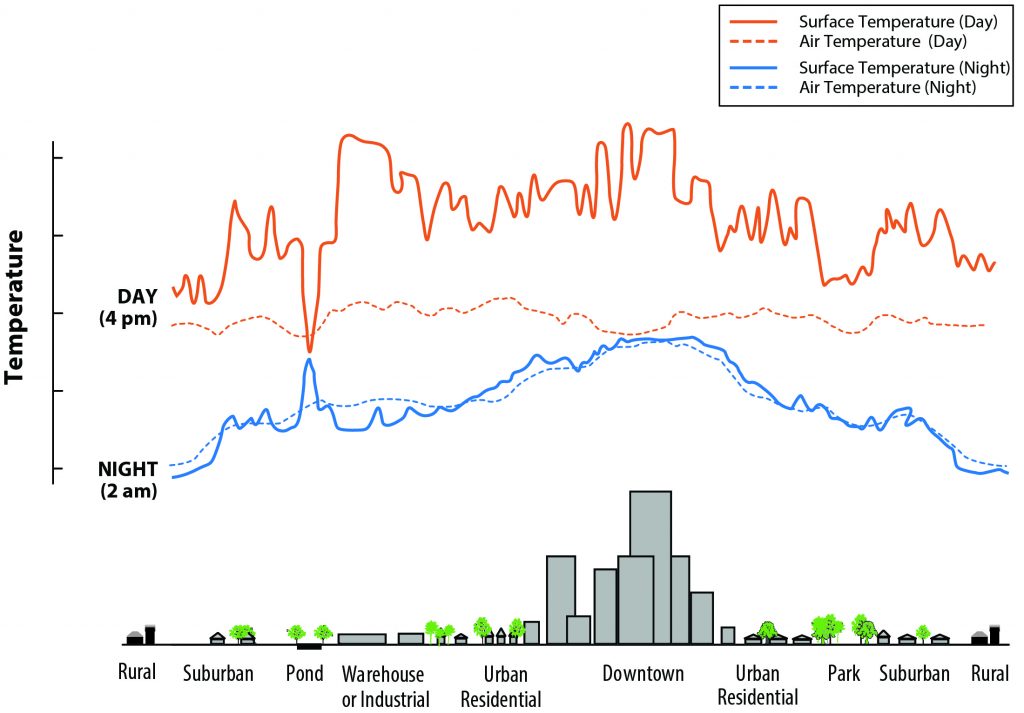

Temperatures inside heat islands can differ as well. Uneven distribution of concrete and blue-green areas causes intra-urban heat islands, meaning that the temperatures inside a city fluctuate too. In the following chart from EPA, we can see green areas are overall cooler than downtown areas:

Pollution

Heat islands also decrease urban ventilation and increase air pollution, and can damage the water quality: “High temperatures of pavement and rooftop surfaces can heat up stormwater runoff, which drains into storm sewers and raises water temperatures as it is released into streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes,” reports the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which can be “particularly stressful, and even fatal, to aquatic life.”

Health Issues

But it’s not only animal life that feels the consequences of heat islands – they increase the risk of heat-related illnesses for us too, such as strokes, lethargy, and dehydration. And because it’s human nature to try and find cooler spaces on hot days, the demand for air-conditioning and cooling energy increases, leading to higher costs and higher greenhouse gas emissions.

1. How Green & Multifunctional Roofs Help

So, how do multifunctional roofs play a part in all of this?

Lower Temperatures

Well, simply put, a rooftop with vegetation won’t become as warm as a traditional, often black, roof. It won’t absorb as much heat during the day, and at night, it won’t radiate the heat back into the city. Roofs on average reach about 60°C, but by having plants, this can be decreased to about 25°C.

Water Management

Having/installing a combined water storage system on the rooftop then makes sure that the plants stay healthy, even in dry periods. And when the roofs with vegetation start to heat up, the plants use the water and vaporise it back into the city. “With this combination, you really start to have a small climate machine on the building,” says Paul. The ‘secret’ is to create a separate layer of sponges, which can soak up the water and create a drainage basin that can store a lot of rainwater under the plants – the higher the sponge layer, the more water the roof can store. Through a capillary function, the sponges help transport the water to the plants above – learn more about the process here.

This is especially crucial in our fast-changing climate, where downpours are becoming the new normal – one multifunctional roof has the potential to store 50 to 100 mm of rainwater, some even up to 250 mm. “And of course, one building won’t save the day, but on a bigger scale, with more roofs, it could,” argues Paul.

Urban Ecosystem

Additionally, with their numerous purposes, multifunctional roofs tackle the heat island effect, high volume of rainwater, and biodiversity loss. “It’s not a solution that will solve all your problems, but it helps to address a lot of issues,” Paul thinks. Curious to learn more? Here’s how such roofs help preserve biodiversity.

Synergy of Methods

As far as the number of adapted roofs needed for a huge difference in temperature, there is no real answer – many factors affect the urban climate.

Ideally, the new basic rooftop should not just be waterproof, but it should also store water, be insulated, be green, and be safe. However, a combination of different methods of greening – on buildings and on the ground – may just be the perfect solution.

“You should always look on different levels,” Paul continues, “do on rooftops what you can on that level, and do on street level, what you can there.” A lot of climate issues are also in soil, in the city’s water, in space for the trees to grow their roots. “You have to look on all levels and start combining them”, he adds.

“We all have to start looking at a city in a three-dimensional way. What functions will you put on a rooftop? What will be on the facades? What can you do in gardens? What can you do in a public space? What do we do on open water? You can never do everything that needs to be done, there are too many climate challenges. We try to start with all the things on the table, and then based on location and the users, look for what is to take care of,” remarks Paul.

“In 100 years, people can tell if we did enough, but we will never reach a point where we say, ‘Okay, now we know we can rest. Now it’s good.’ I don’t believe that. So, we try to focus on the value and value attached for the people involved.”

2. How Green Walls Help

We’ve greened the roof – great. But there is something else we can add to the building to fight the rising temperatures: green walls. Why?

Lower Temperatures

Facades with vegetation can lower the temperature in its area by 2°C, and simultaneously improve air quality. They also directly impact the temperature of a building by shading it from the sun, and therefore reducing the daily temperature of the building by up to 50%, while being able to reflect or absorb between 40% and 80% of solar radiation.

Air Purifying

Plants on walls remove carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and other toxins from the air, reducing CO2 levels that correlate to global warming and warming of the air in the close proximity.

3. How Trees & Vegetation Help

And how do green surfaces on the city’s ground contribute to the reduction of heat islands?

Lower Temperatures

Naturally, trees provide shade. And shade can mean a huge difference on hot summer days: shaded surfaces can be up to 25°C cooler than unshaded ones. Among other things, they help reduce the heat island effect by decreasing the demand for air conditioning due to shading, and through evapotranspiration (emitting ground water through leaves, stalk and surrounding soil, which cools the air).

Air Purifying

Green areas, such as parks, seize carbon and other pollutants created by heat islands, and purify the air.

Breeze Creation

Parks cool the air in the day through evapotranspiration of their vegetation and in the night because plants can’t retain heat as much as concrete, creating a ‘Park Cool Island Effect (PCI)’. This creates cooling breezes, traveling from parks into the city’s neighbourhoods, and thus fighting higher temperatures and the urban heat island effect.

It Can Be Done

De Peperklip in Rotterdam, with its 7,600 m2 of green roof coverage, is the longest natural roof in the Netherlands. It contributes to climate change adaptation, “resilience and biodiversity in the city,” claims Gemeente Rotterdam. There is more about how it works in the following video:

It’s Getting Hot in Here

Whether we want to admit it or not, heat islands are already a huge problem and a great stress on our environment and climate. If there is something we can do to change that, even by adapting our roofs, or planting trees, we should do it. Roofs with vegetation and green areas in the city can help bring the temperatures in too-hot cities to a ‘normal’ level, save the pureness of the air we breathe, help preserve the quality of the water we drink, and bring back natural life.

Read more on how to green your roof, how to incorporate green areas in strategic planning, and how to combine vegetation with architecture – all of which can help fight the heat island effect.