There is one thing women all over the world have in common – fear. Fear of harassment and violence as soon as they enter public spaces. How to conquer this global issue? CityChanger Kalpana Viswanath took the technical approach and co-created an app that helps women figure out which spaces are well lit, well connected and overall feel safe.

Her Work for Women Started…

Kalpana Viswanath is and has long been a driving force in creating safer cities for women. She’s without a doubt an inspiring leader in her field and has been recognised as such in several publications. Recently, she made Apolitical’s list of top 100 influential people in gender policy of 2021 and was mentioned in the 2019 Remarkable Women of Transport Report. We had the pleasure to talk to Kalpana about her app Safetipin, the issue of women’s safety and how feminist cities can be created.

Her work for women started when Kalpana, while doing her M.Phil. and PhD studies at the Delhi University, joined the Jagori team, a women’s resource centre in India.

There, Kalpana worked on creating safe cities for women, and among other things led the Safe Delhi Campaign. Together with UN Women, the initiative focuses on data collection, campaigning and training to improve the safety of women and girls in Delhi.

Moreover, to improve safety and help women overcome obstacles in the city, Kalpana and her team looked at safety audit tools used in Canadian cities and adapted them to the Indian context.

In 2005, numerous safety audits resulted in a report, which was shared with the Indian government and luckily created a lot of momentum. “We reached out to many international groups for their safety audits. There were people in South Africa, in the UK and Australia, Canada. We sort of became part of the global community, looking at public spaces and their safety level.”

This was new in India, as previous work on women’s issues mainly focused on domestic violence and harassment in the workplace. Eager to secure women’s safety in public places – areas women access every day – Kalpana and her team still work closely with the Delhi government and many other cities, for example in Tanzania and Argentina, giving them advice on how to develop city programs to increase safety.

Safetipin – Use Data to Make Cities Safer

While already working on safety audits for many years, in 2013 the overall awareness in India about sexual violence changed due to the 2012 Nirbhaya case, in which the 23-year old Jyoti Singh was brutally beaten and raped. Rightfully so, the outrage and shock were great, not only from governments but for many women this was once again a reminder of the risks they face. Hence, Kalpana and her partner Ashish Basu thought of ideas to make previous safety audits available to everyone. Safetipin was born…

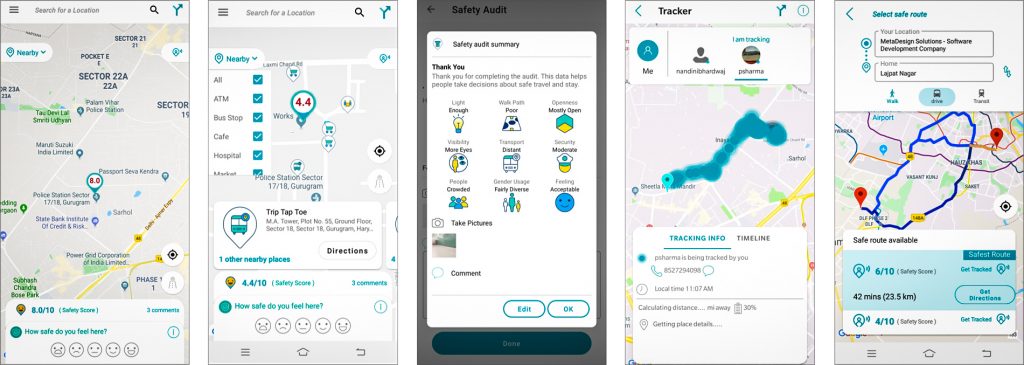

Safetipin works as a social organisation, providing data on how to make cities safer; they offer three services in forms of apps to gather and present data useable for everyone.

The main application, the My Safetipin app, was intended to be used in two ways – make the data available to anyone, and allow everybody to put data in. “You could be walking on the street, and say ‘I don’t feel safe here, there’s not enough lighting’ – that data will become a part of the database.” The app creates user-generated data that women everywhere can access. Kalpana tells us that many young women use this before they rent a house or stay in a hotel because TripAdvisor only tells you if the hotel is good, not whether the street is safe.

To quantify the safety in public spaces, Kalpana and the Safetipin team also created a safety score that proved very beneficial for advocacy with city governments. As we know, politicians love data!

Two additional services run alongside My Safetipin. Safetipin Nite collects photographs at night-time. These are then analysed by Kalpana’s team and the data helps to create a GIS (Geographic Information System) layer of all the lighting in the city, pavements, etc. It’s a tool especially helpful to tell governments exactly what to improve where.

In addition to that, there’s Safetipin Site, a location-specific assessment tool. “Basically, if you want to know more about a park, we set up a survey,” that will analyse the site’s safety with variables such as lighting and public transit access.

Lights Are Not Enough!

My Safetipin is used by women in cities all over the world. Recently, and for a rather sad reason, the number of downloads has risen again, especially in the UK following the Sarah Everard case.

However, the service is not only helpful for the individual female, but also as an advocacy tool for policy changes. Kalpana tells us that many cities have improved their last mile connectivity. “Areas around metros and bus stations were made safer. In Bogota, for example, they use that data to make bicycle tracks safer for women riders.”

Moreover, in New Delhi and other cities, additional streetlights have been added. Indeed, lighting is important but by far not good enough alone to make a city safe. Better public transport access to every part of a city and more walkable streets are necessary. And there is no reason not to focus more on pedestrians, as in India the number of women owning their own private vehicle is fewer than 10%. “We have to address the needs of the vast majority, not the minority who have a car”, Kalpana strongly asserts.

Fear Determines How We Access Our City

But how exactly are women experiencing cities? When we asked Kalpana about the issue in India specifically, she told us that “women’s safety is a global issue. Women feel unsafe in the streets, especially after dark, everywhere.”

The problem is that many places after dark are male-dominated and are therefore rather hostile to women.

“Violence is part of the problem; the bigger problem is the fear of violence. And as women, we are always fearful.”

Fear determines how women access a city. Maybe they will not take a specific job, because they would need to leave in the dark and are scared to do so without sufficient public transport. “Or a girl is not able to take evening classes because there is no good lighting in that area”, Kalpana states.

Other than technological tools such as Safetipin, it is important to bring awareness to the topic. Specifically, men need to be educated about the problem. According to Kalpana “we have to change the man because women already know what they want. We have to create a different kind of model for men to grow up to.” To achieve that, she proposes we start at the very beginning – working in schools with young boys to “create masculinities which are not violent.”

A Feminist City – A Walkable City

When talking about cities safe for everyone you’ll find one description increasingly coming up – feminist cities. The idea of a feminist city is based on the fact that cities until now have been designed by men for men.

To illustrate that issue, Kalpana gives an example within the public transport sector. Take a look at rush hour – it’s the time with the highest frequency of bus or metro trips, it’s the time men go to work. Not that women don’t go to work, but for many, it is not a linear trip; they might have to take their children to school, go grocery shopping or pick kids up from day-care. Women have rarely linear travel trips; hence the frequency of public transport might not be sufficient as soon as rush hour is over.

How to solve this? It’s pretty easy, actually. “We need many more people at the table to design cities; we need young, disabled people, we need people in the LGTBQ community, we need migrants, we need low-income people.”

“We cannot have men in suits designing things for us anymore. We need a diversity of voices!”

Two main things make a feminist city according to Kalpana. A city needs to be walkable, “because then you address everyone’s needs.” A walkable city equals a slower and safer city. Secondly, a city and its design must recognise the work of care. People, many times women, who do a lot of care work have more difficulties in cities.

“A feminist city to me is a really conceptual idea. It’s not just putting up lights. It’s really changing the way that we understand the public domain as something that is a shared space that everyone has the right to use, nobody has more of a right.”

Check out our article about feminist urban planning for more on this!

Leadership Skills Instead of Technological Knowledge

For Safetipin, technology plays a huge role in creating safer environments. As Kalpana tells us, with a PhD in sociology she had no prior technological knowledge, but with the growth of the app, she learnt her way around. “It just grew in a way that I felt a responsibility to learn the thing that I put together.”

In Kalpana’s mind, technology is an enabler: “it’s not the end. The end is making women’s lives better by making cities safer. And the app is a way to do that. Technology for me is always the in-between. My team is working on technology and I keep my eyes on the end. That’s my role!”

Her role has been to lead, and she has done a wonderful job at it. “In terms of being able to create dialogue, I think I’ve been able to generate more people to talk about the issue.” She adds: “leadership is being able to take a new idea of innovation and get more people to be excited and work with you.” Additionally, “I have a great team, a great set of young people who are, in their own way, leaders too in being able to change cities.”

Advice for CityChangers

Kalpana’s advice is simple but significant: “Listen to what people are saying. Open up your ears and open your heart. Listen to what the average citizen wants, the person who has a small shop, the street vendor, the mother who lives a block away from their child’s school, the person who lives on his/her own.”

She goes on saying “once you can hear what people want, you’re going to design an amazing city. I believe we are capable of designing cities where people really are happy, but only if we hear what people want.” We love us some optimism!

With a realistic view on the future, Kalpana is hoping that Safetipin will be used in even more cities around the world, to really secure women’s safety worldwide, and bring change to the average citizen’s life in a city where 2a woman can sit, lie down in a park, or read a book feeling completely safe any time of the day.”