A toxic mix of bad habits and infrastructure that prevents change is holding sustainability back. This is as true for retrofitting as anything. Community sociologist Doctor Jeni Cross has dedicated 20 years to researching the relationship between human behaviour and the systems that surround us. She tells CityChangers.org what challenges this intersection presents and what it tells us about unclogging the pathway to widespread retrofitting.

As a Professor in the Department of Sociology at Colorado State University, USA, and Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Sciences (IRISS), Jeni Cross, Ph.D., is busy! Over the past two decades, our expert has worked on projects across diverse urban and social environments, including public health, schools, corporations, large commercial buildings, and non-profits. Her research delves into the behavioural patterns that form where urban systems push on them. Unbeknownst to us, the built environment, it turns out, intimately shapes our behaviour.

Learnt Behaviour

One day in the not-too-distant past Jeni asked herself a question: how do we use science to make a change in the world?

She now has an answer, and it’s about identifying the right method for solving the issues present. Our CityChanger noticed that we were failing to see the problems for what they really are, which hampered a meaningful resolution.

“Most of the failures are not that the toolkit we use fails, it’s that we misconceptualise the problem.”

That’s why Jeni created a course: Applied Social Change. Rather than social marketing – changing behaviour using marketing tools, as taught by colleagues in business and psychology departments – Jeni approached it from a sociological angle: teaching how to implement “change at different levels, and how the tools at each of those levels are unique”. Students learn to:

- persuade individuals and create individual change,

- create change inside organisations,

- approach larger engagement,

- collaborate between entities.

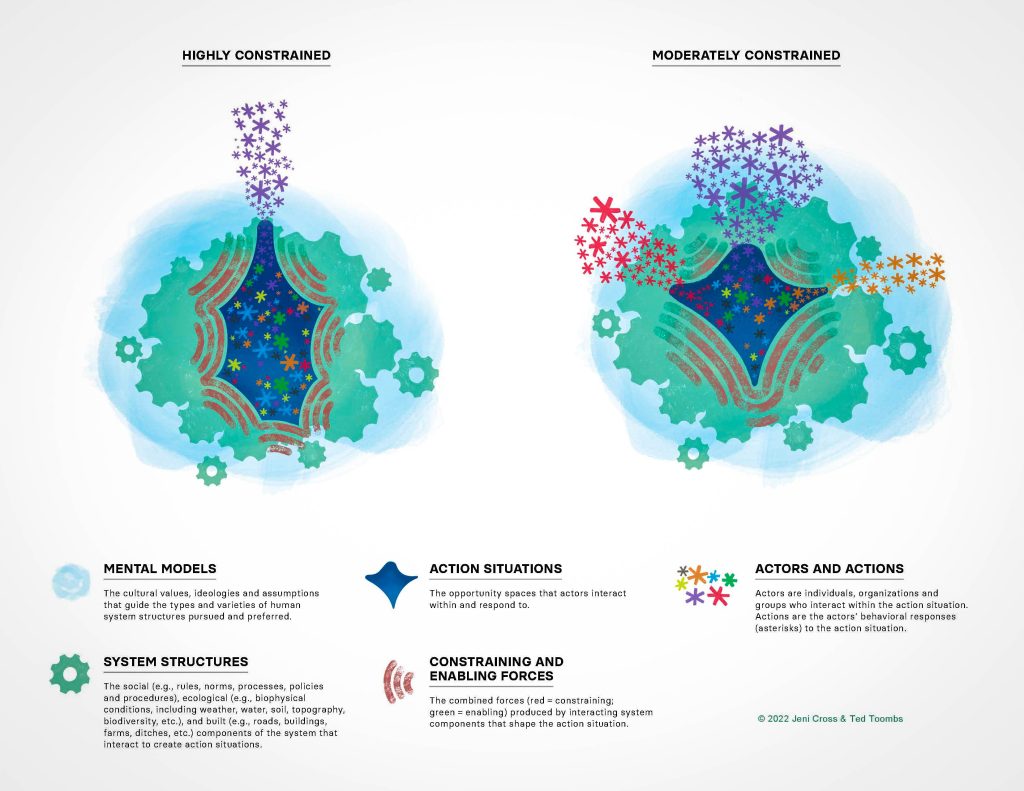

These elements may seem to stand alone, but it’s a nexus. “They’re all an interconnected web, they’re all influencing each other.” To change a system is to exert force on every strand, on the individual and the external constraints that bind and shape us: the natural environment, built infrastructure, social ties, and economic mechanisms. These relationships define Jeni’s work. So much so, that she co-developed the Theoretical Model of Constraint to demonstrate how the interaction of cognitive and cultural influences and physical and social structures can compress and limit the actions we take.

Distributed Action

Take, for example, the motor car. We all know the issues, so why are we still making the same (bad) choices and driving so much? Many believe, says Jeni, that we’re failing to convince people to change their behaviour. But are we in fact moulded by infrastructure designed for the car?

Jeni has a term for these shared bad habits: distributed action problems. If consigned within an organisation, leadership or strategy could alter the direction and erase these issues. But we’re talking about society at large: disparate individuals, all making their own decisions, contributing collectively on a massive scale. It’s hard to halt that.

“Home energy retrofitting is one of these.”

The Trouble with Retrofitting

Residential properties account for around 11% of global emissions. But uptake for retrofitting, which can tackle this problem, is slow. Why?

In what Jeni calls “chaotic organisation”, the system and supply chains are in place but simply “not organised around efficiently making it easy for people to figure out what action to take, and to easily take those actions”.

Finding time to meet with contractors, taking multiple decisions, sourcing affordable quotes from builders and engineers, and understanding the finance options to pay them are baffling! Complexity puts people off.

Although it’s reported that people “would prefer face to face advice” via home visits, Jeni says this isn’t enough. Some cities employ advisors who assess (in)efficiencies and give homeowners a report detailing improvements they can make. But residents “look at it, and they just get frozen. They’re overwhelmed with choices”. The roadblock isn’t caused by indifferent individuals, but by systemic barriers.

Faculty in a LEED Gold building at Colorado State University provide another example. Air vents were installed offering fresh air a-plenty! But they’re always running and it’s cold. So, academics cover the vents with books or masking tape. The vents underperform. Engineers sit at the controls and try to compensate, but they’re unaware of what’s really causing the problem. Then individuals use small space heaters, which raise the buildings temperature, and trip the sensors into adding more cool air. It’s silo thinking at a very localised scale, and it’s disastrous!

Picking the Scab

Systems can either work with us, or not work at all. That takes collaboration, not silos.

“When we think about buildings, you’ve got to recognise that human beings are immensely creative, which means that however a building was designed, or designed to operate, human beings are like terrorists, they look for any crack in the system. They will undo all of your best intentions.”

This raises the question of how “we talk to people and encourage and support them” to access and use information and make choices. We need to reorganise the system “in order to make it easy for all of those people to take the action that we would like to see them taking”. (This is a theme Jeni also touches on in one of our sofa sessions.)

A Broken System

We need to fix the broken systems that keep lots of people doing similar things in the way we don’t want. But how does this ‘brokenness’ manifest? Like Jeni said, we need to understand the problem. Here are some common ones:

A Conundrum of Choice

Often a system is “over-constrained towards bad behaviour”, Jeni says, in one of two ways:

- people “tell you they’re frustrated, because they feel locked in and without very many choices” or,

- they report feeling overwhelmed by too much choice, unclear “where to start, or how to take action”.

Design

“A system can actually be rigged to be unproductive.” Jeni’s words hint at quite a dystopian vision.

It’s how many systems are designed. Like shopping centres on the outskirts of cities accessibly only by automobiles; home heating built to take fossil fuels; farmers needing to use fertilisers to produce enough crops to compete.

As Jeni suggests, “corporations have rigged the system” eliminating the variable of choice for the rest of us.

Dis-Organisations

Institutions are more resistant to change than individuals. The rules and entrenched cultures of organisations make them nigh-on immovable.

We often overlook this, blaming people for being the destructive force. That’s because we can see the actions of people, but not the passive influence of infrastructure.

“The larger the organisation is, the less flexible it is, and the harder it is to get them to make change”, Jeni adds.

Inflexible Infrastructure

Infrastructure is often perceived to be a fixed entity. That’s why we tend to home in on altering people’s cognition instead.

Referring to rewilding in America, Jeni explains that the physical environment isn’t necessarily so stable. Wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park. This impacted the food chain: they hunted elk and deer, reducing overgrazing. Trees flourished, stabilising riverbanks, changing water flows. Animals shaped the landscape.

Sometimes that animal is us.

Talking a Load of Rubbish!

“Education gets you nowhere. That’s a failed strategy.”

It may shock us to hear, but it’s not enough to just persuade people to ‘do the right thing’. The physical world must allow them to follow up on it.

Separating rubbish is an example. If the recycling bin and the waste bin are “even just a few feet from each other, that reduces the rate of recycling”. Not only in the city – it’s ingrained in the human psyche: Jeni cites an investigation into rubbish in the Rocky Mountain National Park where 80% was going to landfill. All it takes is a glance at the giant dumpsters for waste and tiny recycling bins to know why.

The problem, Jeni points out, is that it isn’t enough to just swap out physical collection points and raise public awareness. It involves contractual changes for the waste collection services. The leverage point lies with facilities management and their vendors.

Reshaping Structure

So, how do we unstick the issue of bad behaviours? By jolting the system into a new shape.

“Giving people the opportunity to be cooperative is one of our greatest transformational opportunities.”

Jeni notes that “what that requires is an actor that has the capacity to reorganise the system”. Somebody “in the institution that is empowered or allowed to actually break down those silos”, make decisions, take firm action, and develop the right relationships between the various stakeholders.

This necessitates the institution to be open to a radical shift. Jeni has seen this in Fort Collins where the municipality admitted their retrofit programme wasn’t creating enough traction.

The City of for Collins worked alongside local contractors to establish a menu of options suitable for the local homogenous building stock. This gave homeowners a choice of three: “good, better, and best”.

“Best includes a new heating system and insulation,” Jeni reports, “and maybe new windows, and maybe also solar panels on your house. Good might be just fixing the installation. And then better would be fixing the installation and your HVAC system.”

This is designed to suit a range of interests and budgets: “$20 a month, $50 a month, $100 a month. And you can choose how long you finance it: is it 10 years, 15 years, whatever”, making it affordable.

The City of Fort Collins had to adapt too, absorbing new responsibilities:

- Working with energy providers to incorporate repayments into household utility bills.

- Sourcing local contractors, agreeing on set charges and uniform processes such as how to share the workload.

“What’s different is that we have an actor that is focused on the common good and organises the system so that it’s better for everyone. It’s better for the City, it helps them meet their greenhouse gas emission goals. It’s better for all the contractors, and it’s better for the homeowners. And the result is that more people are retrofitting their homes.” Within a year, Fort Collins witnessed an 44% increase in households taking action based on their energy efficiency assessment.

Systemic Behaviour Change in a Nutshell

Jeni’s research gives us important new understanding in how we can improve home energy efficiency – and sustainability in general!

As sociable animals, humans are heavily, if unconsciously, influenced by the behaviour of our built environment. For us to do the right thing, these need to align so that we are empowered to follow through with the right choice. In terms of a physical change with multiple moving parts like retrofitting, this involves simplifying the process and supporting citizens to understand it and take action. Positive relationships between actors are paramount. As long as someone is willing to take the lead, we might yet see retrofitting become a new social norm.