It’s simple, it doesn’t cost much, it saves time – why aren’t shortcuts more prevalent in cities that want to encourage people to walk more? Look to Trondheim: a mid-sized Norwegian city that has mapped out over 600 shortcuts and continuously upgrades them to get its citizens walking). We sat down with Birgit Høyland, in charge of many walking and cycling projects at Miljøpakken (Greener Trondheim), to find out how it works, what challenges they face, and what other cities can take away from Trondheim’s experience.

Setting the Scene: Getting Around in Trondheim

You might not associate a lot with this fast-growing Norwegian city of 200,000+ inhabitants just yet, but Trondheim’s efforts to make its mobility more sustainable are notable, to say the least. Due to clogged streets and heavy air pollution from personal car use, the city decided on an urban growth agreement through which Trondheim committed to a zero-growth goal, meaning that passenger car traffic should not increase, even if the city grows.

This agreement is also the foundation for Miljøpakken (Greener Trondheim), a partnership for sustainable transport between the city, county, and state. From 2010 to 2029, 25 billion NOK (Norwegian Krone, equals € 2.5 billion) will be invested in (new) roads, bridges, bicycle lanes, and sidewalks to reduce congestion, air pollution, traffic noise, and traffic accidents.

While the biggest part of the budget goes into public transport, around 400 million NOK is assigned to walking measures. To date, about 30% of the overall budget has been used. The results so far are impressive: a 15% reduction in car use through introducing new toll stretches (2009-2017), a 70% increase in the use of public transport (2008-2017), a 51% increase in biking, and a 39% increase in walking to/from the city centre (2010-2017).

In 2016, the city published a walking strategy – rather impressive, given the fact that Trondheim doesn’t have an overall mobility strategy to begin with. One of the main goals is for 30% of daily trips to be made on foot by 2025 (with a starting rate of 27% in 2013/2014). The overall potential is significant: 30% of all trips under 1 km are currently made by car – switching transport modes for short trips is pivotal to reaching that goal, and 1 km is undoubtedly a bearable walkable distance for most people.

While the shortcuts project is only one of many, it has certainly sparked interest: it is characterised by low stakeholder resistance, comparatively low costs, and visible, fast results. It is also very convenient: measurable time savings incentivise people to rethink their transport choice for short distances.

Investing in Shortcuts: How to Prioritise

The shortcuts project was the first major investment by the Greener Trondheim’s walking group. In the first year, 2014, three shortcuts were improved. By the end of 2020, the number had risen to more than 70.

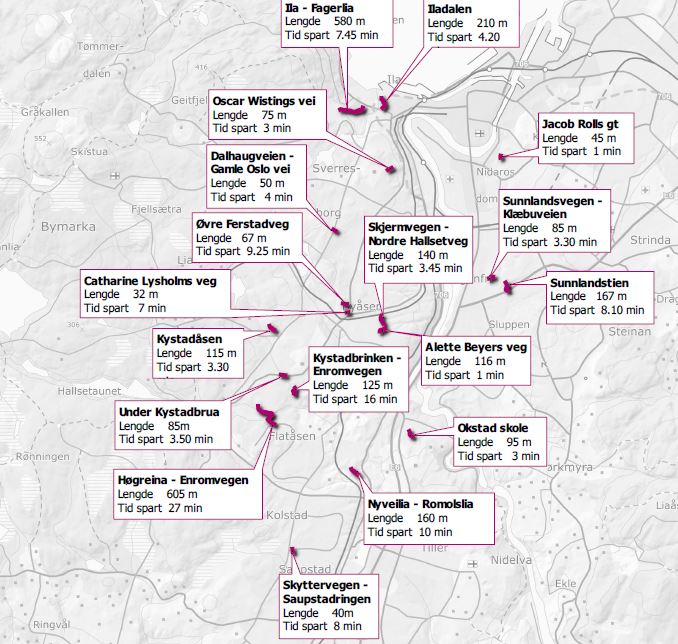

There’s a map including all shortcuts of Trondheim registered, planned, and built here, and a list with extensive information on every shortcut that has been built or improved, including maps, length, time saved, and descriptions. Below is a 2018-2020 overview, but you can find a 2014-2017 overview as well.

Upgrading a shortcut can include features like handrails, better lightning, broadening paths, adding signage, and installing new (non-slippery) pavements, drainage, and benches.

“Compared to new roads and big infrastructure projects, installing or improving a shortcut is a rather cheap option that doesn’t cause a lot of opposition”, Birgit says when asked about the popularity of the shortcuts project. But where do you begin?

The first step is to find out where shortcuts already exist: at the time of writing, over 400 shortcuts are registered around the city. The next step is to evaluate and prioritise: how can you pick those that convince people to walk the most?

For that, all shortcuts in Trondheim are ranked according to their distance to destinations such as schools, public transport stops, green areas, grocery stores, the city centre, or universities. It’s also considered how much time a shortcut would save, and what options the city has to upgrade it.

Even more layers are added to the decision, Birgit explains: “To pick shortcuts with the most potential is the one thing, the other thing is to combine it with the citizens’ opinions and wishes. A third factor is how we distribute shortcuts throughout the city. It shouldn’t be a matter of just a few neighbourhoods but distributed fairly across Trondheim.”

Challenges to Making Trondheim More Walkable

While the shortcuts project runs relatively smoothly, there are walking projects that generate more resistance: “I think the biggest challenge is to work with the main roads where busses, cars, cyclists and pedestrians meet. It’s always a fight about space”, Birgit finds.

The trade association has a powerful lobby, and an unequivocal opinion on taking space away from cars: if there’s not enough space for parking and roads in the city centre, it’s not good for business. Scientific proof doesn’t seem to concern them too much: they haven’t really changed their mindset at all in recent years, which entails a lot of struggle and discussions for walking and cycling projects that relate to the city’s main roads.

Parking regulations are the linchpin for changing people’s behaviour towards sustainable transport options, Birgit is sure: “To get people to change from private cars to public transport, bike, or walking, you need to take away the parking possibilities at people’s work and outside schools. If there are parking spots, they will drive. Parking politics strongly influence how people move – you have to push people in the right direction.”

Political support, in general, is an absolute must for all walking projects – if there is no political case, it will be challenging to get projects off the ground. Currently, Trondheim is working on establishing a new mobility plan for the city centre, including regulations and decisions on how to change main roads and how to make them more pedestrian- and biking-friendly.

The approval of this plan will be the starting point for many of the upcoming walking projects, giving them the power to “overrule” opposition from the trade association. Projects will include new pavements in areas where there are currently none, improving older parts of the city centre, and educating schools and companies, aiming to spark long-term behaviour change.

Advice for CityChangers

There is no one size fits all solution. To find one that might work in your city, Birgit advises checking out walking strategies from other cities and getting external (scientific) input. That way, you can learn what is already out there and get inspired by those that have succeeded with their implementation plans.

Likewise, test projects can pave your way to long-term solutions (even if the test runs are also sometimes costly). It helps people to better imagine and get used to the planned change in their city. Finally, don’t be put off by headwinds or difficulties. Even if a change on one road doesn’t work out, it doesn’t mean that you’re not going in the right direction!