Do we need driverless cars, or carless drivers? Why do we talk about congestion, but not systemic traffic violence? How come John Lennon was in bed with a bicycle? We interviewed the Cycling Professor, a renowned social media activist and academic at the University Cycling Institute, who left us asking even more questions.

The Cycling Professor’s Story: Fishbowls, Honest Brokering and a Very Early Mid-Life Crisis

When asked how he became the ‘Cycling Professor,’ Marco Te Brömmelstroet states that “it starts with the metaphor of the fishbowl. One fish asks another, ‘Hey how’s the water?’ and the other fish responds ‘Water? What water?’. When you live in the Netherlands, the bicycle is the water – it’s one of the last things you think about.”

Marco found that the ubiquity of bicycles in everyday life offered a lens to study society through. “In sociology, it’s called a boundary object” he states, “it’s a relatively simple object, but it unlocks all these questions.”

He points to how gender and class can be traced through cargo bikes, as the ‘SUV- like’ commodity can gentrify neighbourhoods, whilst mathematics can be used to model the interactions of bicycles in shared spaces, “like the choreography of a dance”.

Balancing this detached academic approach, however, with his social media activism has not been easy. “I’m a dispassionate researcher, but I’m also human – it’s hard to decouple”, states Marco.

At the beginning of his academic career, the Cycling Professor had a “very, very early midlife crisis.” Unconvinced that abstract transport articles would have an impact, he set up a bike shop in Munich alongside. “I asked myself what would make me happy. If at the end of the year I helped 200 families switch from the car to the bike, that would make me happy.”

He blogged his experiences of the shop under the name ‘Cycling Professor’, which soon took off. By building bridges from the academic sphere to practice, Marco and the Urban Cycling Institute have since held numerous cycling courses, documentaries and online programmes attended by 9000 students across 125 countries.

“It’s been a much bigger impact than getting 200 families on the bike,” says Marco, “as an academic, the democratisation of that knowledge makes me happy.”

Toying both the theoretical and practical worlds has allowed Marco to be an ‘honest broker’, as he calls it. “When these delegations come to the Netherlands to observe our fish in our aquarium, I try to show the complexity of cycling. Instead of saying this is how wide the bicycle path should be or the ideal density, we teach people to ask better questions.”

What are we optimising with mobility? What are we losing if we design streets in a certain way? Who is prioritised? These are some of the questions Marco poses. “Mobility is disguised as a technical question, but it’s a deeply political and moral question of what we think is good.”

The City as a Machine: We Have Forgotten There Are Choices

The Cycling Professor argues that our approach to mobility is so fixed in a particular mindset that we fail to question it.

“Since the 1920s, streets have been centred around individualism and consumerism, where the homo-economicus must optimise his own utility,” Marco states. As a result, mobility’s purpose is to improve efficiency. Hourly radio updates on traffic congestion, the hyperloop and self-driving cars are the logical manifestation of this.

Marco argues that the neoliberal agenda turned “cities into machines” where individuals must strive for their own mobility, the car, and perceive “everybody else as in the way, which engineers have to solve”.

In the book Het Recht van de Snelste (‘The Right of the Fastest’), Marco and Thalia Verkade claim that this drive for time efficiency gives rise to anti-social traffic, as the fastest are prioritised over the most vulnerable – enabling us to shrug off the 1.3 million road deaths each year.

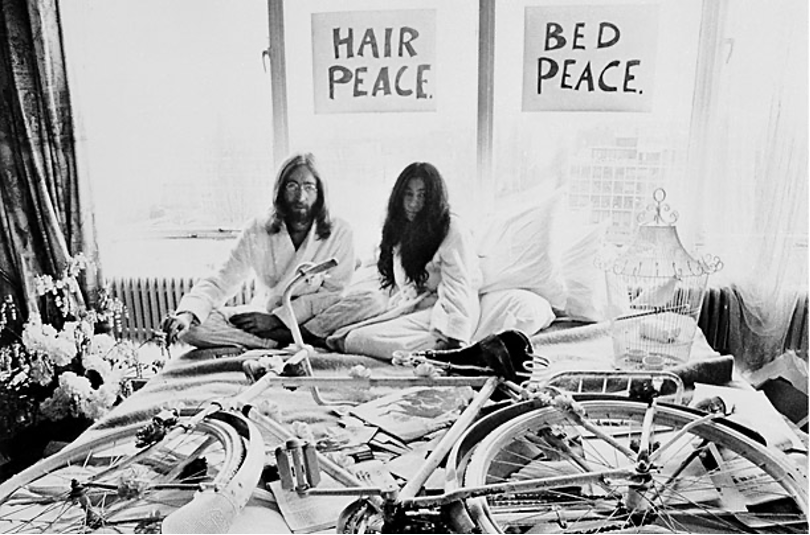

When John Lennon and Yoko Ono famously protested in the Hilton Hotel, Amsterdam in 1968 for world peace, there was a bicycle on the bed. “John Lennon wasn’t in bed with a bicycle because he thought it would solve congestion, or make us faster,” argues the Cycling Professor, “it was because the bicycle was seen as a symbol for a different way of living; a symbol against brutal capitalism.”

People riding bikes do not always take the shortest route, they sit upright rather than aerodynamically, they interact and take in the surroundings. “Either they are very bad homo economicus, or they might show us other elements of what human existence is,” states Marco. “The bicycle offers the potential to re-think society; consider de-growth, values beyond consumerism and whether we want to the future to be faster or slower. The parts we treasure in life are what happened along the way – not how efficiently we got there”.

Asked if the covid-19 pandemic has given us a chance to re-orientate our mobility priorities, the Cycling Professor is not too sure. “The way our streets look is the result of choices which have been solidified into concrete and asphalt, guidelines and norms” he states. “We have forgotten that we can question those choices and change our answers.”

Once the pandemic ends, Marco believes that initiatives like pop-up bike lanes and low traffic neighbourhoods will be dismissed as we revert back to the model of mobility as efficiency. Quoting Robert Pirsig, the Cycle Professor states that “if we don’t use this moment to radically reconsider the foundations of the factory, we will just rebuild the same factory.”

A glimmer of change, however, can been in Paris’s 15-minute city agenda. “One city that gives me hope is Paris,” says Marco, “the mayor got re-elected on based on a radically different understanding of mobility. She’s breaking down this 90-year tradition of traffic engineering which has had a very powerful grasp on our imagination.”

The Cycling Professor’s Advice to CityChangers

For CityChangers hoping to make a difference to their city, Marco urges them to “be aware of the importance of language.”

As he argues in his book, Mobility Language Matters, the words we use solidify our thinking and shape our choices. Talk of ‘car crashes’ rather than systemic traffic violence, congestion ‘problems’ rather than congestion challenges and the disappearance of the word ‘car’ from terms like parking spot, lanes and highways, all cement our current conceptions of mobility.

By being aware of the use and misuse of language, this can then become a powerful tool wield by advocates. “What I do a lot on social media is juxtapose words like, ‘we don’t need driverless cars, but carless drivers’ or ‘instead of autonomous vehicles, we need autonomous children,’” says Marco. “It makes people see something they didn’t see before.”

He argues that real change, however, requires powerful new narratives rather than car-centric terminology. By calling itself the ‘child city’, Mechelen in Belgium has tried to do this: nobody challenges measures to reduce traffic speed and volume when conceived as family-friendly initiatives.

“If it’s possible to radically change the patterns of thought, do it” urges Marco, “because that’s where the real opportunities lie.”

In a Nutshell…

Ultimately, the Cycling Professor argues that the assumptions of efficiency and individualism underlying mobility planning today make for anti-social cities. But by not questioning it, we take these choices for granted – like fish in a fishbowl asking ‘Water? What water?’

Super inspiring, thanks for sharing!