The cohousing project Vrijburcht in Amsterdam was built almost two decades ago. Despite the many difficulties that have cropped up along the way, Vrijburcht has stood the test of time and – over the years – benefitted from a lot of valuable lessons. Menno Vergunst and Johan Vlug, landscape architects and residents of Vrijburcht, shared these lessons with us and took us through Vrijburcht’s epic journey.

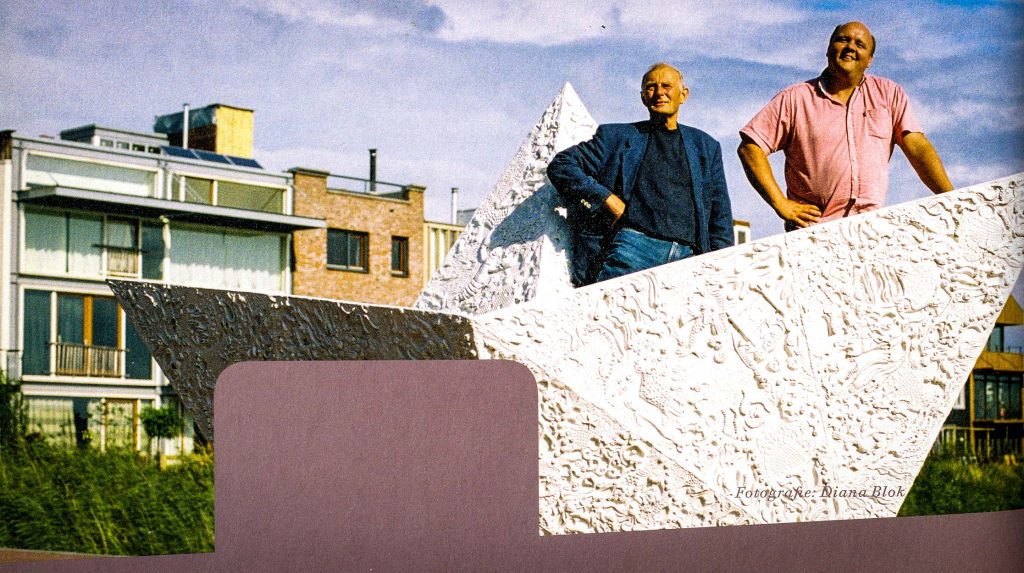

Vrijburcht is a mixed-use cohousing complex located on Steigereiland, an artificial island in Amsterdam. The complex was completed in 2007 but – thanks to its unique concept – is still considered a state-of-the-art cohousing project. To learn more about Vrijburcht and its impact, we sat down with landscape architects Menno Vergunst and Johan Vlug. They were not only involved in the design and construction of Vrijburcht but also among its first residents. Menno and Johan have been living and working in Vrijburcht for more than 15 years, so, naturally, they know the complex’s strengths and weaknesses like the back of their hands.

A Star Is Born

Vrijburcht was first envisioned in 2000. In the same year, the City of Amsterdam launched a building competition for collective self-build projects on Steigereiland. Groups could approach the authorities and put forward a proposal for developing the land.

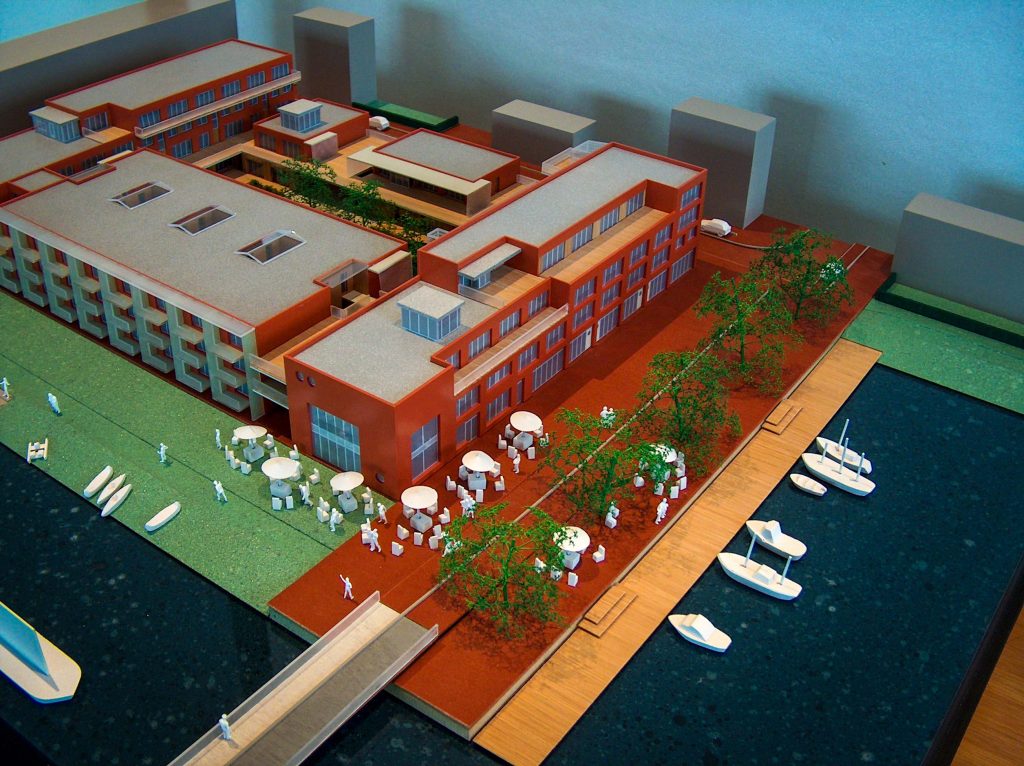

A group of eight friends led by the architect Hein de Haan submitted the Vrijburcht project. Their aim was to create attractive and affordable urban homes surrounded by several cultural, social, and commercial amenities. Thanks to this appealing concept, they succeeded in securing a desirable plot right next to the water and the bicycle bridge connecting the island to the rest of Amsterdam.

Looking for a new place to live and work, Menno and Johan joined the group. Menno became treasurer, and Johan was made chairman.

The Recipe for Success

Altogether, it took seven years to complete the project. That’s a long time, some might argue. However, for Menno, Johan, and their team, it paid off. Vrijburcht is an oasis for urban dwellers, primarily thanks to its mixed-use approach. Apart from 52 private units, residents enjoy many shared amenities, like a workshop, a hobby room, and a communal garden with a greenhouse.

Should you fancy a snack or some entertainment, there is plenty to do too. Be it enjoying a cup of coffee at Café Restaurant Vrijburcht, seeing a show at Theater Vrijburcht, or taking the canoe out, residents don’t have a chance to get bored.

The project also has an important social impact. A day nursery and de Roef, a shared-living unit for young adults with mental disabilities, are located on-site.

When asked how they feel about living in Vrijburcht, Menno and Johan – whose office is also integrated into the complex – burst with pride. “It’s great!”, Menno shares, “you don’t have to travel to your office. Thirty seconds, something like that. When somebody else is in front of me on the staircase, maybe one minute”. Johan smiles and nods.

The Challenges

However, creating such a vibrant and inclusive environment wasn’t easy. Vrijburcht faced numerous hurdles.

Financing

For many community-led housing schemes, financing presents a major challenge. Groups often need to fund the entire project out of their own pockets. Considering that Vrijburcht cost €16 million, it is no wonder that the team encountered some monetary difficulties.

It had started out so well. The Vrijburcht team had opted for a CPO approach (short for Collectief Particulier Opdrachtgeverschap, or collective private commissioning). It’s a financing model where each team member first secures an individual mortgage. These mortgages are then used throughout the construction of the entire complex, i.e., the project is financed and built as a single contract. The team members themselves found a building company, which oversees the construction and coordinates with contractors. Once the project is completed, the building company dissolves, and the ownership of each house reverts to its occupier.

This financing model brings plenty of benefits:

- Residents have full control over the building process.

- Every decision is taken as a group, strengthening bonds “because of the meetings and workgroups that have been organised in advance”.

- Doing a lot of work independently results in huge savings, about 15 to 20 percent in the case of Vrijburcht.

So, what went wrong?

In 2002, two years after the project had first been approved, the “serious financing” was done. At that time, about 90 people had registered their interest in participating and living in Vrijburcht. However, it then became clear that the planning costs alone would amount to €1 million. To finance these costs, each resident had to pay an average of €12,000. If the project failed, this money would be lost. For many, the risk was too high, and they dropped out. Only 12 people remained.

Menno, Johan, and the remaining 10 team members had to solve this issue; and they had to solve it quickly as bills and invoices kept coming. Crowdfunding was not an option back then, and banks were not too keen on lending Vrijburcht money either. Johan laughs:

“They didn’t know how fast they had to run away!”

In the end, the Vrijburcht team approached the Dutch housing association de Key. They agreed to finance any unallocated units and act as a landlord for the café, day nursery, and residential care home. “We were really surprised how fast they agreed to support us with the project. In that respect, they did an important job because it was really a critical moment,” Johan reflects.

Gathering Members

Despite de Key’s support, the Vrijburcht team was in desperate need of more members. This time, they had to make sure to only attract genuinely interested people.

Their search led Menno and Johan to small housing fairs organised by the municipality of Amsterdam. There, they put up a small stand and shared flyers, postcards, brochures, “and a smile” with passers-by.

The team grew gradually. Every once in a while, someone would call Menno and Johan and ask to discuss the project. During these discussions, Menno reveals, he often already knew who was going to stay and who would back out. How? By analysing their questions:

“In the questions they ask you, you recognise, after maybe 10 or 20 meetings, if people are going to stay or not. Because when there are a lot of negative questions, and they don’t trust you, or they have the feeling that they don’t have a grip of it, these people always fall away.”

Johan calls this a “self-selection”. In the end, people participating in the Vrijburcht project actively chose to do so and knew for what they were signing up.

Atmosphere

Cohousing schemes need a great atmosphere. For Vrijburcht, this was not an issue, at least not in the beginning. The project was launched by a group of friends, and everyone who joined in later was welcomed with open arms. Building homes together is a one-of-a-kind bonding experience, after all.

Johan recalls: “We had some parties, and you get to know each other. It’s a very strange idea, when you start living here, then you think, ‘It feels like I’ve been living here already five years or so,’ because you know each other quite well. Your new neighbours are not new anymore. That was really a good feeling. I still remember that very well.”

Despite Vrijburcht’s wonderful atmosphere, some of the original residents have sold their houses – for various reasons. People come and go. It’s normal, but the Vrijburcht team is always conscious of how new residents might influence the project. Menno and Johan explain: “Sometimes we are afraid because the prices are much higher now. So, we are a little bit afraid that now another kind of people is buying those houses.”

Despite their worries, Menno, Johan, and the rest of Vrijburcht have decided against restricting access. Instead, they go with the flow. Each resident has the right to sell their house and does not need to ask the community for permission. However, if a house comes up, existing residents often know someone who is looking for a new home and they make them aware of it.

If it’s not a friend of a friend moving in, most people buying in Vrijburcht still do so because they are genuinely interested in the concept. And, hence, the nice atmosphere and culture of sharing do not get lost, Menno and Johan assure us.

Crucial Advice

Menno and Johan have plenty of valuable advice for those wanting to follow their path. While they stress that “every project has its own experiences because it’s a different time, the money is different, the technical aspects are different,” they share some general tips:

Keep an Eye on the Number of Homes

Cohousing schemes vary in size. For Menno and Johan, the ideal number of homes lies somewhere between 40 and 80. It’s just the right number to guarantee a village-like atmosphere but avoid the gossip and constant chatter. “If you have 20 homes, then you know too much about each other, and you don’t feel comfortable anymore,” Johan reasons.

Ensure Resident Engagement

Even though Vrijburcht’s so-called ‘core team’ tried to engage their fellow residents at every stage of the project, results were often lacking. Menno explains: “We try to communicate every decision we have to make. But afterwards, people say, ‘we want to have more influence on it,’ but when we ask, people don’t want to do it.” Looking back, Menno and Johan think that they should have tried even harder to increase participation and ensure everyone’s voice is heard.

Focus on Progress

Implementing a cohousing – and for that matter, any community-led housing – project can take several years. It took seven in the case of Vrijburcht. When a project is this long, it’s important to keep the momentum going. There should always be something “on the horizon”. Schedule monthly meetings and keep participants updated.

Menno highlights that this is particularly important for people from non-planning-related backgrounds. “Nurses or schoolteachers or a baker” might not understand why it takes so long and could get impatient. It’s up to the core team to communicate what is going on and which steps will follow.

Make It Green

If they could start again from scratch, Menno and Johan confess, they would make their build more sustainable. In the early 2000s, sustainable construction was still in its infancy. While landscape architects Menno and Johan were pushing the group for sustainable designs, the architect thought a building’s social function to be more important.

“He said, ‘Well, it has to do with social housing. And sustainability, we will see afterwards.’ But the construction of a building and the materials you put in it, you can’t change that so much afterwards,” Johan argues. “Nowadays, people can and must pay even more attention to sustainability, energy saving, circular construction, age resistance, and special or purposeful lifestyles,” Menno and Johan underline.

Still, Vrijburcht is largely a sustainable project. For instance, rainwater is stored in underground 6,000-litre tanks for irrigation in dry periods, and plants are creeping up over the building’s façade. The Vrijburcht team also installed a heat recovery system and several well-insulated windows with wooden frames. Recently, they have even added solar panels and greened their roofs.

Vrijburcht in a Nutshell

Over the years, residents of the mixed-use cohousing complex Vrijburcht in Amsterdam have faced and overcome many challenges. They have financed a €16 million project, incorporated many cultural, social, and commercial amenities, gathered likeminded members, and created a great atmosphere. On their journey, they have also learnt what makes a cohousing project successful: the right number of homes, enough resident engagement, constant progress, and sustainable construction.