Indianapolis saw an opportunity. They had plans for a cultural trail, bringing arts, pride, and improved mobility options to the downtown area. This also handed the city a chance to deal with the amount and quality of stormwater returning to nature. The solution was bioswales.

Indianapolis Cultural Trail

Kären Sullivan Haley is the executive director of Indianapolis Cultural Trail Incorporated, a not-for-profit organisation set up in the early 2010s that has created an 8-mile-long linear park in Indiana’s main city.

Rather than a traditional park – an area of land assigned for recreation – this is a network of green routes that connect the many trails that lead out from the edges of downtown – a mix of bike lanes and pedestrian paths running alongside but safely separated from the road. Furnished with trees, grasses, shrubs, and plants, it provides uninterrupted access to the myriad cultural districts spread around the centre.

“If you live along or close to, or you can connect to the cultural trail, you can walk or bike anywhere you need to be,” Kären explains. “It’s filled with moms and kids strolling or rolling to get groceries, to get exercise; it is filled with visitors who are using it to explore the city.”

The Indianapolis Cultural Trail (ICT) is also an attraction in itself. Aside from a mobility and beautification project, 4 million of the overall $63 million USD investment was used to set up an art programme along the trail.

Our CityChanger has observed how businesses use it as a marketing opportunity – they boast of their location on radio adverts – and people clamber to live and work along the route.

“It’s just a beautiful journey while you’re on the cultural trail. It’s really the way by which people experience downtown Indianapolis.”

There’s also a practical benefit: the ICT is designed to manage urban stormwater.

Indianapolis – Prince of Bioswales

Kären leads a team responsible for the long-term sustainable maintenance of the cultural trail, taking care of the horticulture, tree upkeep, garden welfare, and the bioswales.

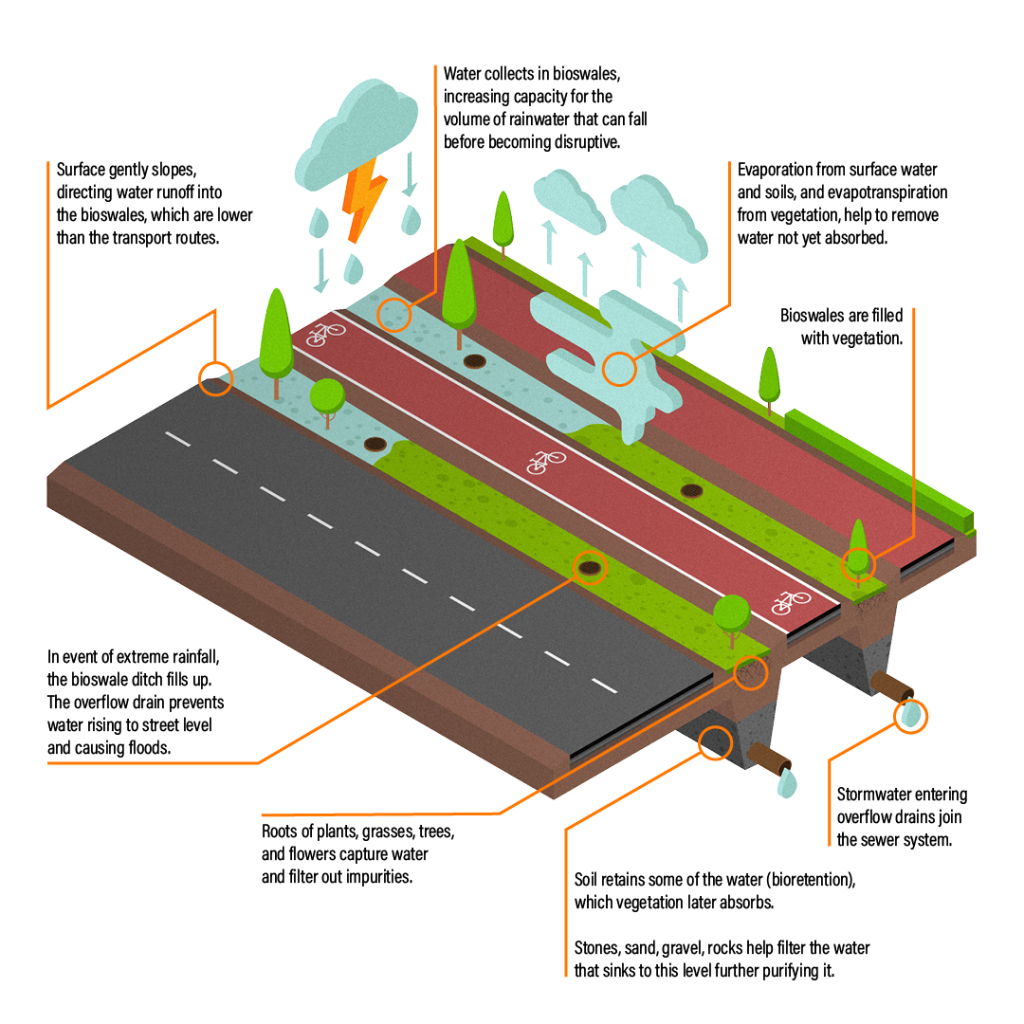

For the uninitiated, bioswales are channels built into the ground into which water is directed to be stored by bioretention and filtered by vegetation and soils.

When it rains, water needs to go somewhere. All the concrete in our cities prevents nature from dealing with runoff. We must be proactive in managing the problem. Indianapolis sets an example of how bioswales can be used to address this challenge.

Why We Need Bioswales

As with many older cities around the world, ageing infrastructure in Indianapolis is beginning to fail.

The city is built upon a combined sewer system. Before the ICT was in place, more than an inch of rain would be enough to trigger the overflow.

The runoff would take all the detritus and polluting elements sitting on the surface into the waterways. Indianapolis in winter is an icy, snowy place: salting the roads leaves an extra contaminant to be washed away, endangering local plant life.

No surprise then that Indianapolis was under a consent decree from the US Environmental Protection Agency – essentially a demand to improve urban water quality.

The innovation of combining stormwater planters and street gardens with the ICT redirected and removed a large volume from the sewer system.

When first built, it added eight acres of green space – including 500 trees and hardy native plants tolerant to winter weather and urban environments. These manage and treat water naturally on the surface before it becomes problematic.

There’s still a failsafe overflow built into the structure, to keep water off the streets even during unprecedented rainfall. But, Kären tells us, in over a decade, this capacity has never been breached.

“I think it’s just a great example of how innovation and thinking about infrastructure differently can lead to these environmental and sustainable benefits,” Kären remarks. In addition, it creates a more liveable city.

How Indianapolis Engineered Success

Bioswales act as the green park or urban garden element of the ICT, doubling as a barrier, and keeping walking paths and the cycle track a safe distance from traffic.

This linear park is not eight straight miles, with a start and end point. It is a green lung carefully landscaped to wind its way along roads and up side streets, incorporated into the fibre of downtown.

“It really makes you feel safe and in a special place when you’re on the cultural trail.”

Even so, the NGO’s closest partner – the City of Indianapolis – had to be convinced at first. Building the ICT in stages was crucial to changing mindsets.

Prototyping

The Indianapolis Cultural Trail is a legacy of local philanthropists Eugene and Maryland Glick. Their seed funding was boosted with support from the Central Indiana Community Foundation. With this in place, the municipality provided access to the civil property upon which the trail is built, so that the non-profit doesn’t have to buy land, and ran the construction project on its land.

This public-private partnership – twinning commitment from the municipality and funding from business or philanthropy – is a typical model in the US, Kären tells us.

Despite this cooperation, city engineers wanted stringent testing carried out over a half-mile section before rolling out bioswales over the full eight miles.

The fact that it’s now being extended further speaks of how well this won over any doubters.

Testament to Economic Prosperity

In the summer of 2022, Indianapolis began adding two miles to the route at an investment of another $30 million USD.

This reflects proven economic benefits.

“The cultural trail has brought beachfront property to Indianapolis”, Kären shares, half in jest. “We have no beaches; we don’t have an ocean.” And yet, the assessed property values along the ICT act as if there was. A study by the Indiana University Public Policy Institute found that these increased by a total of $1 billion USD between 2008 and 2014.

In comparison, values elsewhere in the county largely remained stagnant or reduced.

Our CityChanger explains how “that money goes back to our municipalities and our government agencies”.

Therefore, the revenue generated by the trail benefits the community at large. With the whiff of prosperity in the air, companies have set up along the trail creating local jobs. There’s a robust business case for investing in more stretches of the trail.

A Community Initiative

There are social benefits, too. The ICT improves quality of life. It’s free and accessible to all, 24/7.

“We’ve got our skyscrapers, but you have this beautiful garden setting that has rabbits, that has birds, that has worms, that has butterflies thriving in an urban setting. It’s not easy to have that.”

Regardless of all the benefits, the city doesn’t contribute to maintenance costs, which are significant.

Private utilities companies are responsible for the quality of water re-entering natural systems. They are cooperative, being beneficiaries of the bioswales, but also don’t buy in.

“Philanthropy and generous individuals and foundations have supported the work we do,” Kären informs us. A grant from the Herbert Simon Family Foundation got the trail’s Pacers bikeshare programme off the ground, and a team of up to 5000 volunteers cater for the day-to-day upkeep: litter picking, planting seedlings, weeding, clearing debris from the bioswales – all essential work.

Kären’s team have had to work hard to reach this level of citizen buy-in. Even during the COVID-19 lockdown, they made full use of digital communication channels – social media, e-newsletters, and a series of short videos on bioswales, soils, plant species, and irrigation – to keep interests piqued.

Seeing how Indianapolis have brought together a wealth of stakeholders to rejuvenate, engage, and reinforce their urban environment, other cities are looking to the ICT for inspiration.

“Go Big and Go Bold” – Advice from a CityChanger

At conception, there were no examples Indianapolis could point to and say, “That’s what we want to do!”

If the city wanted to make a go of this idea, they had to test the water.

Looking back, Kären realises there were many elements to pulling this off: visionary funders, a supportive public, a need for change, and a city administration willing to try it out. Developing the infrastructure in segments – and seeing it work – built the trust needed to go big.

“It was something different, and a huge, bold idea. I think that the cultural trail in Indianapolis showed what was possible.”

Now it acts as the point of reference for cities the world over, which Indianapolis never had.

Kären speaks with enthusiasm for how she regularly hosts delegations wanting to mimic the design. They come to “study the cultural trail, learn what it is, how it was built, how it’s managed in a sustainable way with a non-profit organisation” and how the partnerships work.

If it can be done in Indianapolis, she believes, it can be done anywhere.

“Everyone, every city, every community, no matter what size, can build their version of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail. And it’s game changing.”

But, our CityChanger reiterates, incorporating bioswales into city planning and infrastructure design alone is not enough. A lesson learnt from the ICT is that bioswale maintenance must be included in long-term city plans.

“You’re gonna get all kinds of debris in them, all kinds of city runoff. And so how are you planning for that long-term care so that they continue to function and can be examples for others in the future?”

It’s all very well hoping for an army of volunteers to help out, but a city serious about managing excess urban water should allocate a sensible budget and expertise base.

“It’s expensive,” Kären admits, but so is clearing up after a flood – or sending polluted water to treatment plants. “You get what you pay for.” What a city must ask itself is, isn’t a clean, green, functioning, happy, future-proofed city worth the investment? Indianapolis thinks so.